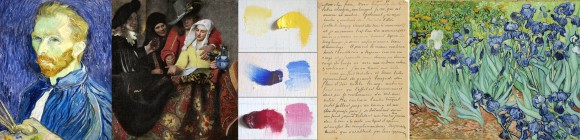

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam reopened after seven months a few days ago, 1 May – the culmination of a renovation process which I briefly discussed over at amsterdamarm. The new exhibition which marks the museum’s reopening is entitled Van Gogh at Work, and is the product of eight years of research undertaken by the Van Gogh Museum, the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, and researchers from Royal Dutch Shell. This research has brought various confirmations and some new insights regarding Van Gogh’s working practices, his artistic techniques, and his use of materials. We now know, for instance, that during Van Gogh’s two years in Paris, he bought his canvases from the same shop as his colleague Toulouse-Lautrec; and have gained a sense of the frequency with which he recycled canvases, painting over works or utilising both canvas sides.

The research also extends and establishes our understanding of the way in which some of Van Gogh’s pigments have changed and faded through the course of years. The resulting change in the colour of some of Van Gogh’s paintings is the central theme of articles written about the reopening in The New York Times (‘Van Gogh’s True Palette Revealed‘) and The Guardian (‘Van Gogh’s true colours were originally even brighter‘).

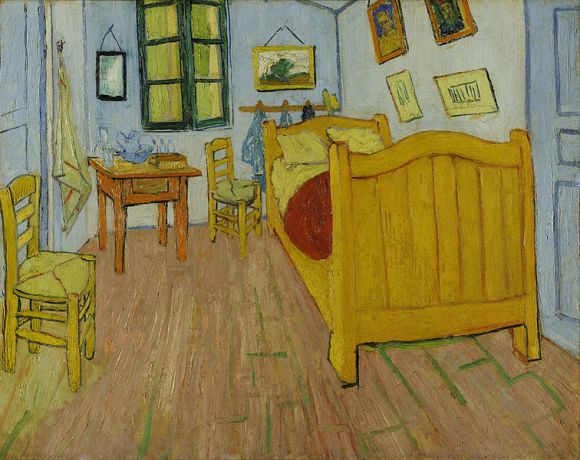

The New York Times piece discusses in particular Van Gogh’s The Bedroom (or Bedroom in Arles). The title refers to three oil paintings: the first painted in Arles in October 1888; the subsequent two painted after the original, in September 1889, whilst Van Gogh was a patient at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, in Saint-Rémy. The New York Times focuses on the initial painting, held by the Van Gogh Museum; and explains that, whilst its ‘honey-yellow bed pressed into the corner of a cozy sky-blue room’ is so familiar to us today, in fact Van Gogh originally painted the walls of the room in violet. The red pigment which he used to mix this violet has faded over time, leaving only the blue. Marije Vellekoop, the Van Gogh Museum’s head of collections, research and presentation, comments, ‘For me, the purple walls in the bedroom make it a softer image. It confirms that he was sticking to the traditional colour theory, using purple and yellow, and not blue and yellow’.

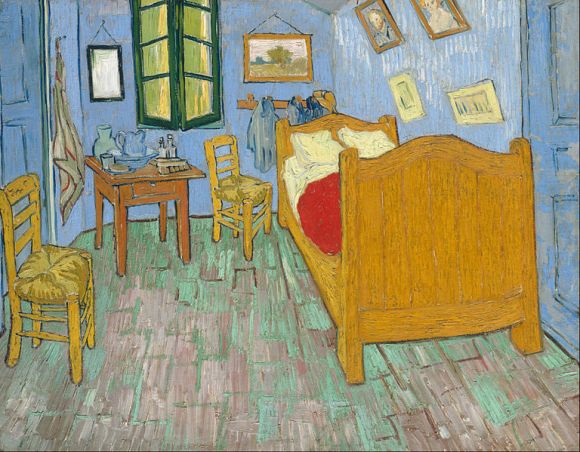

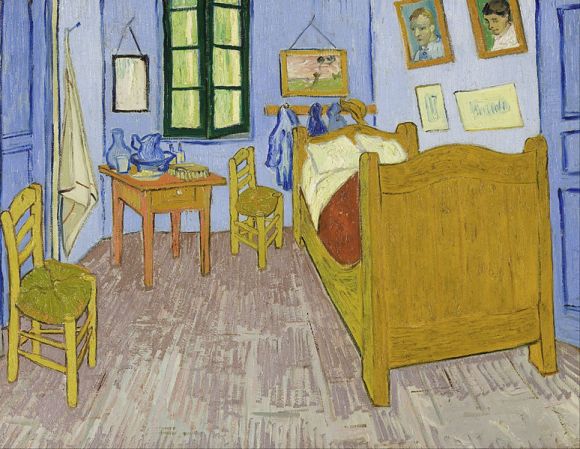

This diminishing of pigment is less evident in the two Saint-Rémy paintings. The second version of The Bedroom, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, shows more intense, cornflower-blue walls. This version is on loan from Chicago for the duration of the Van Gogh Museum’s exhibition, displayed side-by-side with the Arles rendition. The third version of the painting, held by the Musée d’Orsay, bears more trace of the original violet, the colour of its walls approaching lavender.

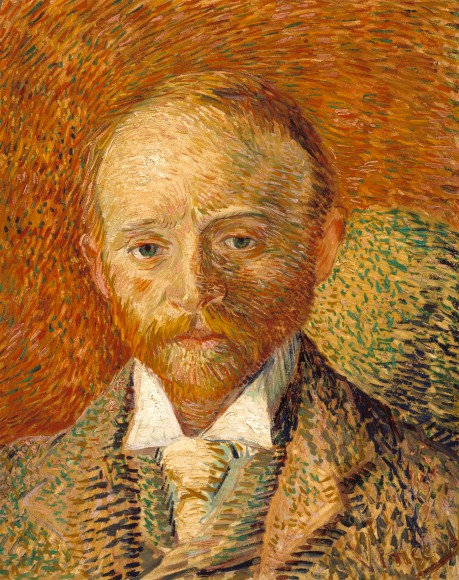

The emphasis in the New York Times on these particular colour combinations – on violet and yellow becoming blue and yellow – relates to my series on Van Gogh, inspired by the previous collection of his works at the Hermitage Amsterdam. The first piece in that series, published early last month, is titled ‘Gauguin’s Chair and La Berceuse: Conceptualising Red and Green in the Art of Van Gogh‘. The second piece, published at the start of this week, discusses ‘Van Gogh in Paris: The Radicalising of a Palette and a Brush‘. In it, I depict the months he spent in Antwerp, between late 1885 and early 1886, as crucial to Van Gogh’s artistic development. It was in Antwerp that he studied colour theory and began to broaden his palette; inspired as he was upon arriving in the city by the busy, varied life of its docks, and by the Japanese woodcuts he found on sale there.

This, the third piece in my series, considers precisely the occurrence of a violet and yellow contrast becoming a contrast of yellow and blue. Namely, I want to view Van Gogh’s Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, and compare it with Johannes Vermeer’s The Milkmaid.

Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background was one of the last paintings Van Gogh worked on in Saint-Rémy. He completed it in May 1890, before leaving the hospital and moving to Auvers-sur-Oise; where – after achieving dozens more canvases, including his innovative double-square paintings – he would die at the end of July. In marked contrast with the rest of his artistic career, Van Gogh painted relatively few still lifes during his time at Saint-Rémy, painting instead outdoors, in the hospital’s gardens and then in the surrounding countryside. Though he frequently appreciated the order imposed by life at the hospital, and painted prolifically, he continued to experience periods of deep anguish and physical illness.

After suffering what the director of the asylum described as an ‘attack’ on 22 February, Van Gogh kept painting, but wrote few letters over the next two months (he received letters meanwhile from Theo and Gauguin among others; his paintings had recently been shown at Les XX’s annual exhibition in Brussels, and with the Artistes Indépendants in Paris, to the warm acclaim of his fellow artists). This attack motivated his decision, made in early May, to leave for Auvers. Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background was therefore presumably undertaken with his move already firmly in mind. In a couple of letters, Van Gogh writes of working in a ‘frenzy’ during his last few days in Saint-Rémy.

He had completed two studies of irises, out in the garden of Saint-Paul, the previous May, soon after committing himself to the asylum following his time in Arles. Theo greatly admired these, and submitted them to the Société des Artistes Indépendants’ annual exhibition in September. Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background was one of two still lifes with irises which Van Gogh painted a year after these studies. In his own words, in a letter to Theo,

At the moment the improvement is continuing, the whole horrible crisis has disappeared like a thunderstorm, and I’m working here with calm, unremitting ardour to give a last stroke of the brush. I’m working on a canvas of roses on bright green background and two canvases of large bouquets of violet Irises, one lot against a pink background in which the effect is harmonious and soft through the combination of greens, pinks, violets. On the contrary, the other violet bouquet (ranging up to pure carmine and Prussian blue) standing out against a striking lemon yellow background with other yellow tones in the vase and the base on which it rests is an effect of terribly disparate complementaries that reinforce each other by their opposition.

The crisp contours of the leaves and the Japanese-influenced diagonals of the flowers are set against a background which moves thickly around them. Indeed, Van Gogh painted this background last, after the flowers and vase. Yet in the painting as it appears today, the carmine – that pure, rich red which Van Gogh mentions as a facet of it – only faintly remains. As with The Bedroom‘s walls, the violet flowers have turned blue. In this manner, Van Gogh’s art makes explicit the idea that all art is involved in a continual process of becoming. In the particular case of Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, Van Gogh’s painting has become a perfect Vermeer: echoing in its current form Vermeer’s predisposition for the bold and brilliant use of yellow and blue.

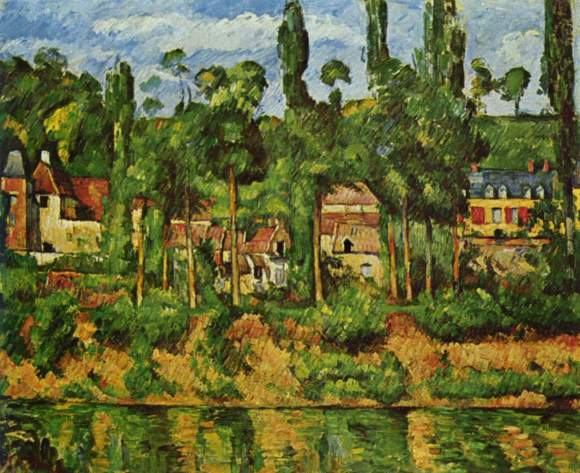

Vermeer’s The Milkmaid evinces both this predisposition for colour and his strikingly modern painterly techniques. It was painted around 1668, when Vermeer was just twenty-five years old. In some respects Vermeer is a difficult artist to analyse, for only 34 paintings remain attributed to him, and there is a dearth of material and information relating to his studies and preparatory methods. He appears about 1665 already remarkably accomplished and mature. Broadly, there is something readier, a little rougher, more captured than composed about his earlier works.

Yellow and blue are the dominant colours of The Milkmaid. In the organisation of these, Van Gogh’s Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background appears like The Milkmaid reversed. The distinguishing feature of Vermeer’s palette, when contrasted with those of his contemporaries, was his use of expensive natural ultramarine: this gives his blues here an exceptional vividness, in tune with his similarly luminous handling of lead-tin yellow. Yet the colour combinations in The Milkmaid are complex and various, and not limited to yellow and blue. The contrast in these colours is repeated in the rich contrast between the green of the tablecloth and the maid’s carmine-red skirt.

The same green depicts the milkmaid’s rolled oversleeves, which Vermeer painted alla prima (wet-on-wet), mixing and working the yellow and blue of the maid’s shirt and apron. This method was not uncommon amongst Early and Golden Age Dutch painters: it was adopted by Jan van Eyck and by Rembrandt for several of their compositions. It became a characteristic of many Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, aided by the new availability of pigments in portable tubes, which allowed artists like Van Gogh to go out into nature and paint rapidly en plein air.

A further aspect which links Vermeer to the art of the Impressionists is his use of a pointillé technique – patterns of small dots which, to a modern eye, evoke the pointillism of Seurat and Signac, with which Van Gogh experimented. Collections of small, white dots add texture and suggest the play of light in Vermeer’s painting, noticeable especially on the bread and on the top of the maid’s apron; highlighting also her cap, oversleeves, and the lip of the jug with which she pours. They enhance the atmosphere of softly diffusing light which characterises this brilliant but gentle, boldly restrained, most harmonious of works.