Archives For November 30, 1999 @ 12:00 am

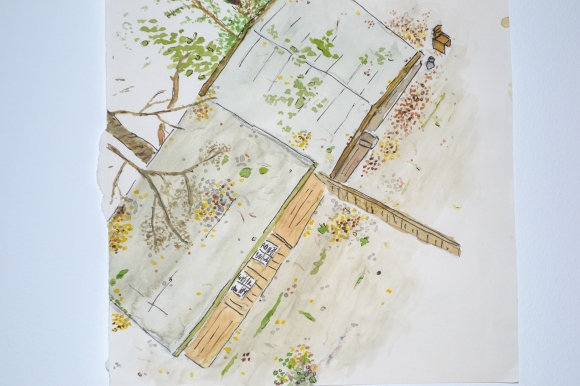

And so here lies a second painting, in ink and watercolour, of the view from the rear balcony of my old apartment in the Oud-Zuid neighbourhood of Amsterdam.

While the first looked down from the balcony toward two sheds, showing their roofs and yards in autumn with the patternation of fallen leaves, this watercolour shows a perspective across the complex of apartments. I always appreciated the view sitting out on this balcony because – while enclosed – the distance and design was sufficient so that you could be aware of the presence of bodies on other balconies, but rarely noticed anything egregious in their expressions or behaviours. In short, you were well secluded – and the situation reminded me a little of Rear Window, though to the cinema’s potential loss, I never suffered while living there a broken leg.

At the end of last October, my partner and I departed Amsterdam and returned to York. The cause was my commencing a PhD in literature at the University of York. While there were possibilities for undertaking doctoral research at a university which would have enabled us to continue living in Amsterdam – including an excellent opportunity with the University of Antwerp – we ultimately decided that York presented the best scenario for study. Preparations for the move occupied much of late October; there was the fact of the move itself; and then followed the process of finding and inhabiting an apartment in York while also developing a working habit at the University.

That serves as a loose explanation for my lack of posts between last September and mid-March; but as much as I was preoccupied with other things, I simply fell out of the habit of posting. More, during September and October, I began and wrote significant portions and passages for articles which were intended for the site, but never finished. Aside from no longer possessing a surfeit of time, and aside from the diminishing of a regular article-writing habit, the existence of these unfinished pieces served to further pervert the end of publication. As those articles which I had begun became less and less relevant, the inclination was to consider how their material could be repurposed – rather than focusing on what else I ought to write. What had been written became a barrier to further work. The situation in Ukraine and Crimea compelled several pieces last month, and marked my return to posting.

In the last few weeks before we left Amsterdam, I painted a small number of paintings comprising views from the rear balcony of our apartment, in the ‘Oud-Zuid’ of the city. The paintings are in watercolour and ink. Some of their views will be visible in earlier collections of photographs posted on this site; or else via my Instagram account. This first painting looks down upon two sheds, and contains all of the relevant fallen leaves and foliage.

As a sort of coda or poetic epilogue to the series of photographs of Sweden which I posted last week, here are ten visuals: nine photographs of the late-evening mist, and one video of the falling sunlight upon a lake, all taken across several nights at Norra Renbergsvattnet, outside of Skellefteå.

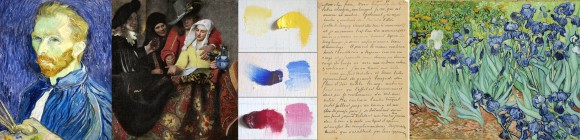

In early April, I began a series on the art of Vincent van Gogh. Propelled by a thematic display of his works at the Hermitage Amsterdam, my series continued on as these works were removed and transported back across the city for the reopening of the Van Gogh Museum, on 1 May, and with a new exhibition, entitled Van Gogh at Work.

The first piece in my series centred on psychological interpretations of the use of red and green in a number of Van Gogh’s paintings: Gauguin’s Chair, La Berceuse, and The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital. The second piece provided an overview of Van Gogh’s early artistic career, through Brussels, Etten, The Hague, and Nuenen, before viewing the emboldening of his art during the time he spent in Antwerp and Paris. The third piece considered new research undertaken by the Van Gogh Museum into Van Gogh’s artistic practices and use of pigments; and compared his Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background with Vermeer’s The Milkmaid. So in turn these three short essays saw Van Gogh in Arles from late 1888 to the spring of 1889, prior to his installation in the asylum at Saint-Rémy; in Antwerp from late 1885 to early 1886, then in Paris over the next two years; and towards the very close of his year in Saint-Rémy, just as he was about to move on to Auvers-sur-Oise.

It is rare that any endeavour is completed – so many of our tasks are cyclical, looping, or intermittently repeating; and work started upon tends to encourage more ideas, to bring about new prospects, to demand ever-more work. This piece in my series draws from the research and the concerns of the others, and views Van Gogh during his early days in Arles, in the spring of 1888. Van Gogh left Paris for Arles in February. Just as he moved from Antwerp to Paris struggling with ill health – the effects of an insufficient diet, and excessive drinking and smoking – so the move further south was made with Van Gogh ill and seeking a kinder climate. More, he had become exhausted with life in Paris, and sought for his art to be reinvigorated by Arles’ light and its exotic atmosphere.

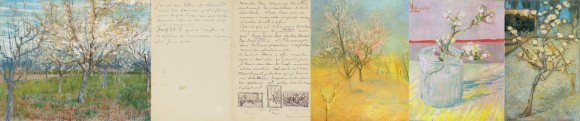

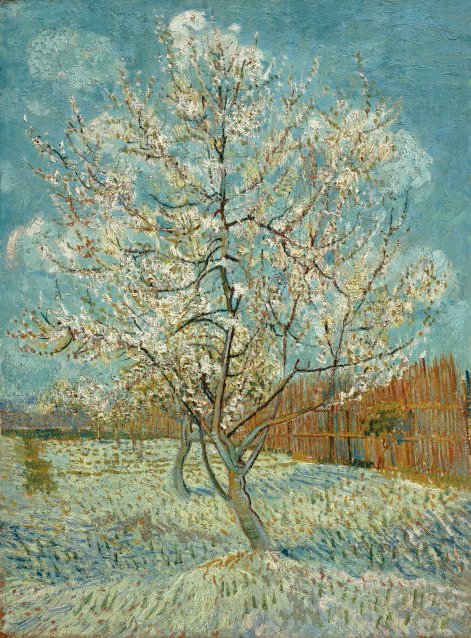

Though he had become close with Paul Signac living in Paris, and had experimented with pointillism, Van Gogh met Georges Seurat for the first time only in the hours before his departure from the city. Vincent arrived in Arles on 20 February. He found the town under a cover of snow; and began staying in accommodation at the Restaurant Carrel. Immediately setting about his work, between the beginning of March and the end of April he completed fifteen paintings of trees and orchards in blossom. These were prefaced by two still life studies, ‘Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass’ and ‘Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass with a Book’: the movement between indoors and outdoors, between still life paintings and painting en plein air, was always a fluid movement for Van Gogh; and he kept objects and themes in mind, dwelling on them in sustained short bursts, often returning to them in the longer term.

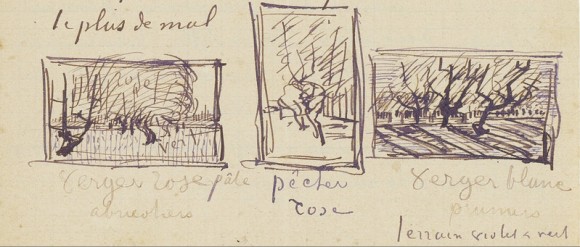

Of the fifteen blossoming orchard scenes he completed, three stand out because, in a letter to Theo on or around 13 April, Vincent explicitly tied them together as a triptych. These are The Pink Orchard (also known as Orchard with Blossoming Apricot Trees), The Pink Peach Tree (or Peach Tree in Blossom), and The White Orchard. Vincent included in his letter a sketch of this triptych. He was increasingly fond of linking his works in such a way, and would later envision his Sunflowers in triptychs, one either side of a La Berceuse. While stating his desire to paint repetitions of his blossom paintings, and his hope to complete at least nine canvases in total – with the implication that these nine canvases would divide into three triptychs – we have no information regarding which of the other finished paintings Vincent may have intended to go together.

In fact, even Vincent’s ink-sketch is not decisive: The Pink Peach Tree is almost identical in composition with The Pink Peach Tree (Souvenir de Mauve), which was the second painting in the blossom series, completed just after The Pink Orchard (The Pink Orchard and Souvenir de Mauve were the first two paintings in the series, from March; whereas The Pink Peach Tree and The White Orchard were the last two, finalised towards the end of April). We can conclude that The Pink Peach Tree is the painting Van Gogh conceived for the triptych because, in a letter to his sister Willemien on 30 March, he expressed his intention to send the earlier painting to the widow of Anton Mauve. Mauve was Vincent’s cousin-in-law and had been an important figure in Van Gogh’s early artistic development; Vincent sent Souvenir de Mauve to Theo in May, and it was subsequently passed on to Mauve’s widow Jet.

Together, the three paintings of the triptych show Van Gogh developing upon the techniques and inspirations of his time in Paris. There is the bold use of vivid colour; and the influence of ukiyo-e Japanese prints evident in his cropped, asymmetrical compositions and his rhythmic lines and contours. In fact, Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige), from the autumn of 1887, is a distinct precursor to the series.

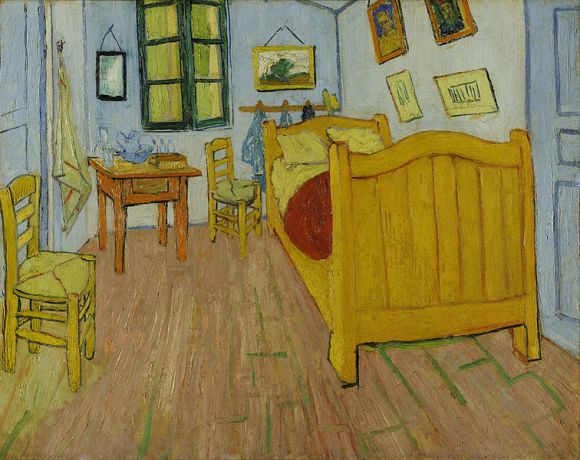

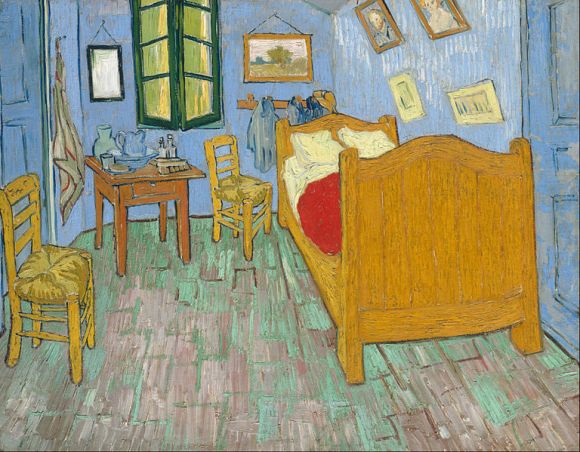

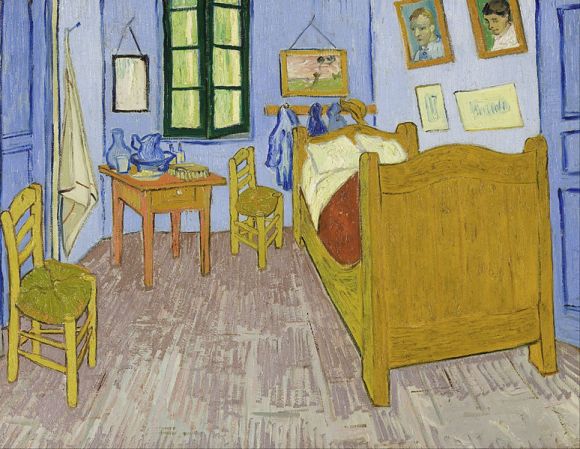

Just as in some of his later paintings – including The Bedroom, painted in Arles in October 1888, and Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, painted in May 1890 in Saint-Rémy – the canvases here too demonstrate the diminishing of red pigment over time, for the pink blossom which was present in the first two paintings of the triptych, as indicated by their titles, has faded and become predominantly white.

In The Bedroom and Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, Van Gogh would mix red pigment with blue to arrive at violet-purple. Contrasting this purple with a range of yellows, Van Gogh was thereby remaining true to traditional colour theory, which he had studied in Antwerp. As the red pigment which he utilised has faded, the palette of these two paintings has changed from yellow-purple to yellow-blue; two colours which, while not strictly opposing on the colour-wheel, remain highly complementary. The disappearance of so much pink in Van Gogh’s blossom paintings perhaps represents, therefore, a greater change to the nature of these works and the way they are viewed and considered. With the red pigment’s absence leaving only the white behind, these works take on a luminous, spiritual quality.

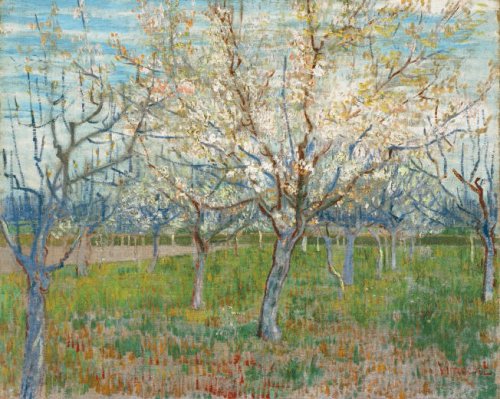

The Pink Orchard well demonstrates the range of painterly techniques which Van Gogh had by this point developed. It features short brushstrokes of red and green for the grass in the foreground, painted thinly and with the canvas showing through – characteristics of some of his paintings of Parisian streets and gardens in Montmartre. Its trees rise in tones of ultramarine, with blue contour lines and bare branches. The composition moves diagonally, from the near left to the far right; this was the first blossom painting Van Gogh painted, early in the season after a long winter, and many of the trees are not in bloom; the handful of trees in the centre which are blooming show flowers painted in impasto, now predominantly white, but with highlights of pink and orange. Set against the contours of the trees and a light-blue, almost turquoise sky, which moves horizontally behind the branches, the painting divides loosely into two colour contrasts: the red/green of the ground, and the blue/oranges of the sky above.

The Pink Peach Tree shows an impasto application of paint throughout, with flowers painted so thickly that they all but hang from the canvas. The central colours here are in the white of the ground and the blossom, in their green highlights, and in the thick blue-turquoise sky painted and suspended around the blossom flowers. The fence to the right of the composition is painted in long verticals and with a diversity of colours again reminiscent of Van Gogh’s 1887 Montmartre paintings; its oranges, browns and reds offset the central, titular, sky-bearing tree, and juxtapose with the lower greens and upper blues.

The White Orchard is the most evenly painted of the three works, and appropriately the one with the least pink in the blossom of its trees. Their white and green blossom, resting upon blue branches, is counterbalanced by the pinks and purples – in fact, mauves – which highlight the ground. This orchard appears in full blossom, the branches of its trees entangling against a delicate sky.

The popular conception of Van Gogh often seems one of a headstrong, difficult and solitary artist; whose relationships with the opposite sex were ill-conceived and ultimately short-lived; who concluded perhaps the most famous co-habitation in the history of art by cutting off his own ear; who went unrecognised in his lifetime; and who died alone in Auvers-sur-Oise. The difficulties he had within specific relationships cannot be denied, and that there was a strong solitary strain to his personality is also clear. In October 1876, years before he embarked upon his artistic career, in a Methodist church in Richmond, England, Van Gogh delivered his first sermon, and opened with the belief ‘I am a stranger on the earth’. Yet this sense of Van Gogh alone does not account for the complexities of his personality, or for the connections he sought and the very real connections he made.

In Paris, Van Gogh became acquainted with Émile Bernard, with whom he began corresponding, especially during his time in Arles, and with Lucien Pissarro; both men would attend Van Gogh’s funeral in Auvers. Of the older Pissarro, Van Gogh would frequently ask Theo to pass on any painterly advice he gave; and he entertained the idea of lodging with Camille, for the sake of Camille’s finances, and towards his own improvement as an artist. In addition to Signac, in Paris Van Gogh worked closely with Toulouse-Lautrec. Toulouse-Lautrec’s use of the peinture à l’essence technique, where oil paint first rests on paper for several hours so that some of its oil is absorbed, and is then thinned with turpentine before being applied to canvas – a technique which Toulouse-Lautrec himself derived from Degas – was borrowed and experimented with by Van Gogh for some of his paintings of Paris and Montmartre.

From the very first, Van Gogh had moved to Arles not only for its light and vibrant colours, but also with the conception of forming an artist’s colony – or at least a retreat which his fellow artists could visit, and from which there would derive inspiration, and the intermingling of diverse ideas. The Yellow House was to be the centre of this vision, and Van Gogh encouraged Gauguin to come and stay there and decorated the house for his arrival. Even after Gauguin left Arles after only two months, at the end of December 1888, still he and Vincent remained in contact, and would resume friendly terms. On 20 March, 1890 – whilst Van Gogh suffered through a sudden, prolonged illness – Gauguin sent him a letter commenting on the recent display of ten of Van Gogh’s paintings at the Artistes Indépendants exhibition in Paris:

It’s above all at this latter place that one can properly judge what you do, either because of things positioned beside each other, or because of the neighbouring works. I offer you my sincere compliments, and for many artists you are the most remarkable in the exhibition. With things from nature you’re the only one there who thinks.

At the Les XX exhibition in Brussels a couple of months earlier, the Belgian Symbolist painter Henry de Groux had taken exception to being exhibited alongside Van Gogh, and had insulted those of Van Gogh’s works on show. In his absence, Van Gogh was defended by Toulouse-Lautrec and Signac, who both challenged De Groux to a duel. De Groux was expelled from Les XX.

Van Gogh’s blossoming orchard triptych hangs today in the Van Gogh Museum, the three paintings shown in white frames alongside a work by the Danish artist Christian Mourier-Petersen. Mourier-Petersen was another painter who Vincent readily befriended and worked alongside. From a wealthy Danish family, he had been a student of medicine before turning to art, which he studied in Copenhagen in 1880. Having undertaken a proposed three-year Grand Tour of Europe, he spent from around 10 October, 1887 until 22 May, 1888 in Arles; before moving on to Paris, where he lodged with Theo from 6 June to 15 August. Van Gogh wrote warmly of Mourier-Petersen and regarded his intelligence, but thought little of his paintings. Mourier-Petersen – who admitted finding Van Gogh a little mad at first – would send Vincent a friendly letter in January 1889, having returned to Denmark upon the conclusion of his travels.

Mourier-Petersen painted with Van Gogh in Arles during the months of March and April. His Blossoming Peach Tree views precisely the same scene as Van Gogh’s The Pink Peach Tree. Perhaps seated slightly to the right of Van Gogh when he painted the scene, Mourier-Petersen’s work features three trees: aside from the one upon which Van Gogh’s composition centres, there appears a tree just behind and to the right in even fuller blossom, and a small shrub positioned in the foreground which serves to frame the work. The shrub’s flowers are white; but Mourier-Petersen’s flowers for the other two trees have remained a vivid pink.

Where the impasto of Van Gogh’s flowers makes their blossoming palpable, felt as vigorous explosions of the spring, Mourier-Peterson’s paint is thinner and his style gentler, with his trees elongated, stretching upwards in their frailty in contrast to Van Gogh’s relatively squat and sturdy depictions. A golden-yellow hue stretches across the extent of the fence in the middle of Mourier-Peterson’s canvas; his fence lilts forwards; the ground comes in tones of pink-orange with silver-blue highlights; and the sky distends in heavy purple-blue.

________

The full text of Van Gogh’s first sermon, Sunday, 29 October, 1876: http://www.vggallery.com/misc/sermon.htm

Here are a selection of documents and sources – videos, images, and text – relating to and referred to in the piece I just published, on the influence of Nicholas Roerich and Asiatic culture on Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

____

Mikhail Glinka, Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842) – Overture

____

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, Op. 35 (1888)

____

Vladimir Soloviev, ‘Pan Mongolism’ (1894)

–

Pan Mongolism! The name is monstrous

Yet it caresses my ear

As if filled with the portent

Of a grand divine fate.

–

While in corrupt Byzantium

The altar of God lay cooling

And holy men, princes, people and king

Renounced the Messiah –

–

Then He invoked from the East

An unknown and alien people,

And beneath the heavy hand of fate

The second Rome bowed down in the dust.

–

We have no desire to learn

From fallen Byzantium’s fate,

And Russia’s flatterers insist:

It is you, you are the third Rome.

–

Let it be so! God has not yet

Emptied his wrathful hand.

A swarm of waking tribes

Prepares for new attacks.

–

From the Altai to Malaysian shores

The leaders of Eastern isles

Have gathered a host of regiments

By China’s defeated walls.

–

Countless as locusts

And as ravenous,

Shielded by an unearthly power

The tribes move north.

–

O Rus’! Forget your former glory:

The two-headed eagle is ravaged,

And your tattered banners passed

Like toys among yellow children.

–

He who neglects love’s legacy,

Will be overcome by trembling fear…

And the third Rome will fall to dust,

Nor will there ever be a fourth.

____

Golden bull figurine, from the Maikop kurgan (excavated 1897)

____

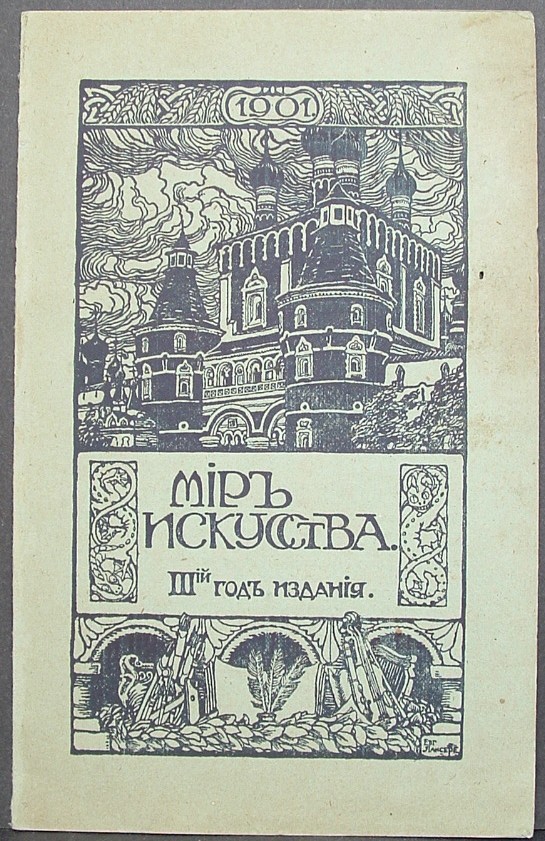

World of Art magazine, 3rd Edition (1901)

____

Nicholas Roerich, Guests from Overseas (1901)

____

Nicholas Roerich, Set Design for Act III of The Polovtsian Dances (1909)

____

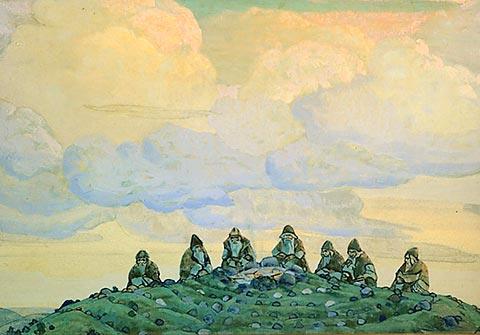

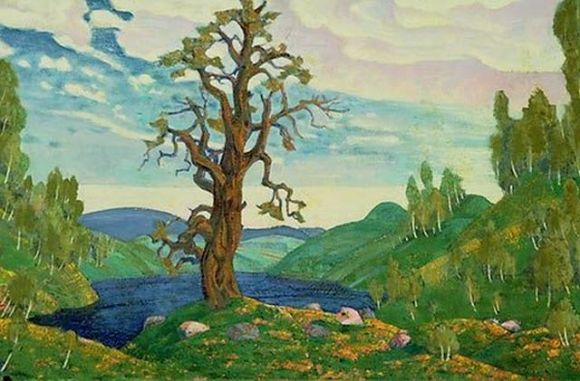

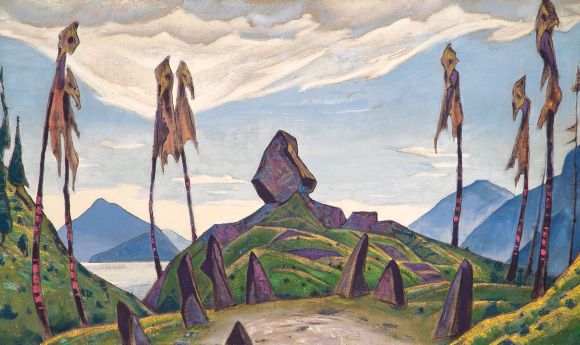

Nicholas Roerich, Preliminary Paintings for ‘The Great Sacrifice’ (the working title of The Rite of Spring) (1910)

____

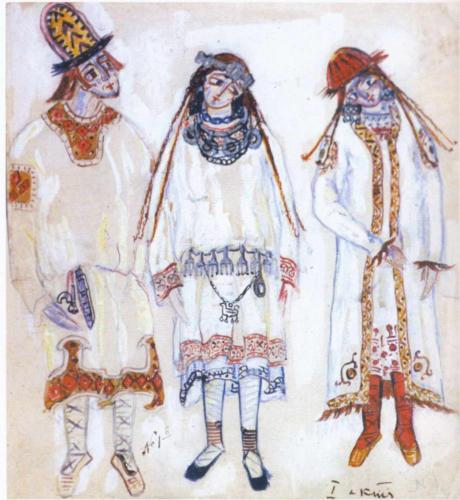

Nicholas Roerich, Costume Designs for The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Nicholas Roerich, Set Designs for The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Original Costumes for The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Alexander Blok, The Scythians (1918)

–

You are millions. We are hordes and hordes and hordes.

Try and take us on!

Yes, we are Scythians! Yes, we are Asians –

With slanted and greedy eyes!

–

For you, the ages, for us a single hour.

We, like obedient slaves,

Held up a shield between two enemy races –

The Tatars and Europe!

–

For ages and ages your old furnace raged

And drowned out the roar of avalanches,

And Lisbon and Messina’s fall

To you was but a monstrous fairy tale!

–

For hundreds of years you gazed at the East,

Storing up and melting down our jewels,

And, jeering, you merely counted the days

Until your cannons you could point at us!

–

The time is come. Trouble beats its wings –

And every day our grudges grow,

And the day will come when every trace

Of your Paestums may vanish!

–

O, old world! While you still survive,

While you still suffer your sweet torture,

Come to a halt, sage as Oedipus,

Before the ancient riddle of the Sphinx!..

–

Russia is a Sphinx. Rejoicing, grieving,

And drenched in black blood,

It gazes, gazes, gazes at you,

With hatred and with love!..

–

It has been ages since you’ve loved

As our blood still loves!

You have forgotten that there is a love

That can destroy and burn!

–

We love all- the heat of cold numbers,

The gift of divine visions,

We understand all- sharp Gallic sense

And gloomy Teutonic genius…

–

We remember all- the hell of Parisian streets,

And Venetian chills,

The distant aroma of lemon groves

And the smoky towers of Cologne…

–

We love the flesh – its flavor and its color,

And the stifling, mortal scent of flesh…

Is it our fault if your skeleton cracks

In our heavy, tender paws?

–

When pulling back on the reins

Of playful, high-spirited horses,

It is our custom to break their heavy backs

And tame the stubborn slave girls…

–

Come to us! Leave the horrors of war,

And come to our peaceful embrace!

Before it’s too late – sheathe your old sword,

Comrades! We shall be brothers!

–

But if not – we have nothing to lose,

And we are not above treachery!

For ages and ages you will be cursed

By your sickly, belated offspring!

–

Throughout the woods and thickets

In front of pretty Europe

We will spread out! We’ll turn to you

With our Asian muzzles.

–

Come everyone, come to the Urals!

We’re clearing a battlefield there

Between steel machines breathing integrals

And the wild Tatar Horde!

–

But we are no longer your shield,

Henceforth we’ll not do battle!

As mortal battles rages we’ll watch

With our narrow eyes!

–

We will not lift a finger when the cruel Huns

Rummage the pockets of corpses,

Burn cities, drive cattle into churches,

And roast the meat of our white brothers!..

–

Come to your senses for the last time, old world!

Our barbaric lyre is calling you

One final time, to a joyous brotherly feast

To a brotherly feast of labor and of peace!

____

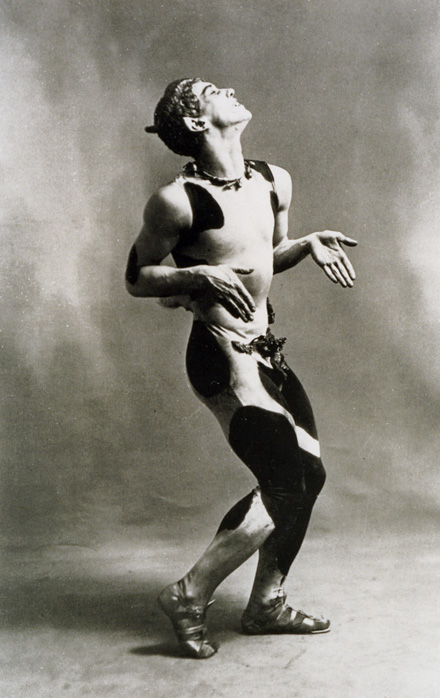

Vaslav Nijinsky

____

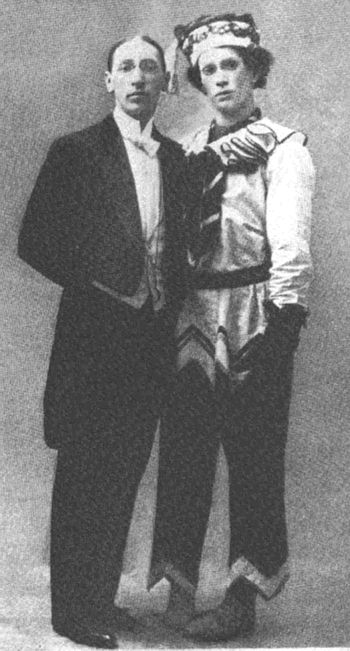

Stravinsky and Nijinsky

____

Credit for the two poems goes to From the Ends to the Beginning: A Bilingual Anthology of Russian Verse; a project hosted at: http://max.mmlc.northwestern.edu/~mdenner/Demo/index.html

Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (in French, Le Sacre du printemps) – the third ballet which Stravinsky composed for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, after The Firebird (1910) and Petrushka (1911) – was written for the 1913 Paris season, and premiered just over a hundred years ago, on 29 May, in the newly-opened Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The centenary of this most notorious premiere is the occasion for numerous celebrations: new performances, revivals, and festivals which will extend across the next year. The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées is hosting a range of balletic and orchestral performances, in a programme led by Saint Petersburg’s Mariinsky Ballet. In Moscow, four choreographies of the work have been shown by the Bolshoi Ballet over the last two months; with their performance of Pina Bausch’s interpretation set to travel worldwide. The Barbican and the Southbank Centre in London will feature orchestral performances of Stravinsky’s music. Carolina Performing Arts at Chapel Hill have devoted the next year to various showings of the work.

In Amsterdam, as part of the Holland Festival, the Chinese-born choreographer Shen Wei has produced a new version for Het Nationale Ballet. The Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel – which houses the Stravinsky archive – and Boosey & Hawkes are publishing a three-volume centenary edition comprising essays and an annotated facsimile of the score. In Zurich, David Zinman – who studied under and served as assistant to Pierre Monteux, the conductor of The Rite of Spring premiere – will investigate the musical and literary facets of the Rite with the Tonhalle Orchestra on 8 and 9 June. It is something of this endeavour which this piece will also attempt: an exploration of the cultural currents in Russia, centring on conceptions of the East, which led to the development of The Rite of Spring.

The influence of Asiatic art on Russian art, and in the realm of music in particular, was especially evident from the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Mikhail Glinka, the father of Russian classical music, drew extensively in his compositions from Russian folk music, which he had heard growing up as a child near Smolensk, and which was being annotated and collected from the last decade of the 1700s. Glinka’s Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842), an opera in five acts based on Pushkin’s poem, is considered an example of orientalism in music owing to its use of dissonance, chromaticism, and folk melodies. Following Glinka’s lead, Mily Balakirev began combining folk patterns with the received body of European classical music.

Balakirev utilised syncopated rhythms, while Orlando Figes – in Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia – argues that his key innovation was the introduction into Russian music of the pentatonic scale. The pentatonic scale has five notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven and which characterised much of the European music of the common practice era between 1600 and 1900. While the pentatonic scale has been diversely used, it is a prominent aspect of South-East Asian music, and is a facet of many Chinese and Vietnamese folk songs. Figes asserts that Balakirev derived his use of the pentatonic scale from his transcriptions of Caucasian folk songs; and writes that this innovation gave ‘Russian music its ‘Eastern feel’ so distinct from the music of the West. The pentatonic scale would be used in striking fashion by every Russian composer who followed…from Rimsky-Korsakov to Stravinsky’.

Balakirev was the senior member of the group of composers also comprising Modest Mussorgsky, Alexander Borodin, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and César Cui – known variously as The Five, The Mighty Handful, and the kuchkists (‘handful’ in Russian being ‘kuchka’, (кучка)). Balakirev’s compositional manner aside, the central philosophical force upon this group was Vladimir Stasov, who as a critic relentlessly forwarded a national school in the Russian arts. Balakirev’s King Lear (1861), Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition (1874), and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sadko (the name for a tone poem of 1867, and for the opera of 1896) and Scheherazade (1888) were all dedicated to Stasov.

From the early 1860s, Stasov researched and wrote a series of analyses demonstrating the influence of the East ‘manifest in all the fields of Russian culture: in language, clothing, customs, buildings, furniture and items of daily use, in ornaments, in melodies and harmonies, and in all our fairy tales’. His extensive study of the byliny, traditional Russian epic narrative poems, led him to conclude ‘these tales are not set in the Russian land at all but in some hot climate of Asia or the East…There is nothing to suggest the Russian way of life – and what we see instead is the arid Asian steppe’.

While positing the influence of the East was one thing, stating that these traditional Russian songs were in fact not Russian, but had originated entirely elsewhere, drew for Stasov considerable criticism. Any picture of the relationship between Russian and Asiatic art is complex: the developing understanding of this relationship in Russia throughout the 1800s is entwined with so many political and artistic movements and events: the emergence of orientalism after Russia’s annexing of the Crimea in 1783, and while they fought the Caucasian War between 1817 and 1864, which gave Russians a new awareness of and access to the south, and which impelled Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time; the persisting influence of Western Europe, encouraged in literature by the critic Vissarion Belinsky; and the Slavophilism which opposed the predominance of the West, seeking instead the emergence of a truly distinct Russia rooted in its own past. This Slavophilism gained momentum after the Crimean War from 1853-1856, which saw the British and French empires join the Ottomans against Russia. It was inextricably linked with the Orthodox religion; bore the related pochvennichestvo ‘native soil’ movement; and implicated in different ways Nikolai Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Such complexities are encapsulated in a piece Dostoevsky wrote for his A Writer’s Dairy – a periodical he wrote and edited, containing polemical essays and occasional short fiction – in 1881. Dostoevsky, an ardent Slavophile for much of the second-half of his life, advocates for the progress of Russia through an engagement with Asia which will, at the same time, renew Russia’s relationship with Europe:

‘It is hard for us to turn away from our window on Europe; but it is a matter of our destiny…When we turn to Asia, with our new view of her, something of the same sort may happen to us as happened to Europe when America was discovered. With our push towards Asia we will have a renewed upsurge of spirit and strength…In Europe we were hangers-on and slaves, while in Asia we shall be the masters. In Europe we were Tatars, while in Asia we can be Europeans.’

All this is the long background to The Rite of Spring. The Symbolists who would achieve a Silver Age of Russian Literature were influenced by a combination of orientalism, folk tales, European literature, their Russian forebears, and some of those philosophers and mystics who were a product of the heightened religious thinking that was so much a part of Slavophilism. The philosopher Vladimir Soloviev – a close friend of Dostoevsky – has been characterised by D. S. Mirsky as ‘the first Russian thinker to divorce mystical and Orthodox Christianity from the doctrines of Slavophilism’, thereby establishing a metaphysics apart from nationalist sentiment. Mirsky depicts Soloviev as leaning towards Rome in matters of theology, and as a Westernising liberal politically. Yet he too was fascinated with the East. An important figure for Andrei Bely – whom Mirsky places alongside Gogol and Soloviev as the three ‘most complex and disconcerting figures in Russian literature’ – and for Alexander Blok, Blok’s The Scythians takes for its epigraph two lines from Soloviev’s 1894 poem ‘Pan-Mongolism’: ‘Pan-Mongolism! What a savage name!/Yet it is music to my ears’.

The Scythians was Blok’s last major poem, completed in 1918, just after The Twelve. Mirsky calls it an eloquent piece of writing, but ‘on an entirely inferior level’ as compared with ‘musical genius’ of The Twelve. Its title references the group of poets of the same name: an offshoot of Russian Symbolism in so far as it consisted of its two leading figures, Bely and Blok, plus the writer Ruzumnik Ivanov-Razumnik.

The Scythians as an ethnographic group were nomadic Iranian-speaking tribes, who inhabited the Eurasian steppes around the Black and Caspian seas from about the eighth century b.c.. Herodotus believed that, after warring with the Massagetae, they left Asia and entered the Crimean Peninsula. In literature, ‘Scythian’ increasingly became a derogatory term to describe savage and uncivilised people. Shakespeare refers to ‘The barbarous Scythian’ in King Lear; while Edmund Spenser sought to declaim the Irish by positing that they and the Scythians shared a common descent.

Alexander Pushkin used the term more warmly in his poetry, writing ‘Now temperance is not appropriate/I want to drink like a savage Scythian’; and in the Russia of the late nineteenth century, it came to be used to infer those qualities of the Russian people which marked them apart from Western Europeans. Abetted by archaeological excavations of Scythian kurgans (burial mounds) on Russian soil, a shared heritage with the Scythians was hypothesised as ‘Scythian’ became a byword for Russia’s historical past, Russian character, Russian otherness, and thereby also for Russia’s future.

Emphasising the conflux of Eastern influences in The Rite of Spring, Orlando Figes argues that Stravinsky’s ballet ought to be viewed particularly as a manifestation of this interest in all things Scythian. The painter Nicholas Roerich had initially trained as an archaeologist. He had worked with the archaeologist and orientalist Nikolay Veselovsky in excavating the Maikop kurgan in Maikop, Southern Russia, in 1897. The Maikop kurgan was dated as far back as the third millenium b.c., and revealed two burials, containing rich artifacts including a bull figurine made of gold. Roerich was an adherent of Stasov, and when he began work on a series of paintings depicting the early Slavs, he sought Stasov’s advice regarding ethnographic details. Stasov advised him that wherever there was a lack of local evidence, it was appropriate to use artistic and cultural details from the East since ‘the ancient East means ancient Russia: the two are indivisible’.

Though the specifics of his background and his orientalism were not entirely fluent with the group’s more worldly outlook, Roerich became an entrenched figure in Diaghilev’s World of Art movement. After designing the sets for The Polovtsian Dances – a ballet excerpted from Borodin’s opera Prince Igor, which featured during the Ballets Russes first season in 1909 – Roerich went on to work with Stravinsky on the concept, setting and costumes for The Rite of Spring.

The idea for The Rite of Spring had emerged by 1910; Petrushka, which premiered a year later, two years before The Rite of Spring‘s own premiere, was the product of a very different core of people. While Diaghilev quickly became the prominent figure in the movement – owing to his bold entrepreneurial personality; his appetite for and ability to synthesise knowledge; and driving the publication of the magazine of the same name from 1899 – the World of Art (‘Mir iskusstva’ (Мир иску́сств)) originally comprised a group of Petersburg students around Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst. Mirsky describes Benois as ‘the greatest European of modern Russia, the best expression of the Western and Latin spirit. He was also the principal influence in reviving the cult of the northern metropolis and in rediscovering its architectural beauty, so long concealed by generations of artistic barbarity…But he was never blind to Russian art, and in his work…Westernism and Slavophilism were more than ever the two heads of a single-hearted Janus’.

The World of Art embodied these two poles, and was part of the energetic and diverse avant-garde in Russia in the first decade of the 1900s. This avant-garde also included the Symbolists in literature, and Alexander Scriabin in music – an influential composer who experimented with forms of atonal music, and who was much loved by Stravinsky. After Diaghilev’s successes staging Russian opera and music in Paris towards the end of the decade, the Ballets Russes was formed. Bakst produced scenery for the company’s adaptation of Scheherazade in 1910; while Benois designed the sets for many of its earliest productions. He worked especially on Petrushka. Mirsky suggests that not only the set design but the very idea of the ballet ‘belongs to Benois, and once more he revealed in it his great love for his native town of Petersburg in all its aspects, classical and popular’. Both Scheherazade and Petrushka were choreographed by the established dancer and choreographer Michel Fokine.

When it comes to locating the genesis of The Rite of Spring, Lawrence Morton has asserted the probable influence on Stravinsky of Sergey Gorodetsky’s mythological poetry collection Yar. Stravinsky set two of Yar‘s poems to music between 1907 and 1908. He claimed that the idea for the ballet came to him as a vision, of a ‘solemn pagan rite’ in which a girl danced herself to death for the god of spring. Yet Roerich had written in 1909 an essay, entitled ‘Joy in Art’, which depicted ancient Slav spring rituals of human sacrifice. Figes argues the concept for the ballet was originally Roerich’s, and that ‘Stravinsky, who was quite notorious for such distortions, later claimed it as his own’; Thomas F. Kelly, in writing a history of the ballet’s premiere, has argued much the same thing.

Whatever, by May 1910 Stravinsky and Roerich were discussing together their ideas for the ballet. A provisional title, ‘The Great Sacrifice’, was quickly decided upon. Stravinsky spent much of the next year working on Petrushka. Then in July 1911, he visited Roerich at Talishkino, an artist’s colony presided over by the patron Princess Maria Tenisheva, where the scenario for the Rite – ‘a succession of ritual acts’ – was fully plotted out.

Figes considers that the ritual which the ballet explicitly evokes may have been based on Roerich’s archaeological research, during which he had found some evidence of midsummer human sacrifice among the Scythians. The switch from summer to spring was motivated partly by an attempt to link the rite to traditional Slavic gods; and ‘was also based on the findings of folklorists such as Alexander Afanasiev, who had linked these venal cults with sacrificial rituals involving maiden girls’. While Stravinsky composed the ballet, Roerich worked on the sets and costumes, which were rich in ethnographic details: drawing from his archaeological studies, from medieval Russian ornament, and from collections of traditional peasant dress.

The controversy of the ballet’s premiere in Paris is often conceived as Stravinsky’s. He wrote in his autobiography of the mockery of some members of the audience upon hearing the opening bars of his score, which built upon Lithuanian folk songs; and the orchestra were littered with projectiles as they performed. Other critics, however, have forwarded Roerich’s costumes as the ballet’s most shocking aspect. Others still, including the composer Alfredo Casella, felt that it was Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreography which most drew the audience’s ire. Figes writes:

‘the music was barely heard at all in the commotion…Nijinsky had choreographed movements which were ugly and angular. Everything about the dancers’ movements emphasised their weight instead of their lightness, as demanded by the principles of classical ballet. Rejecting all the basic positions, the ritual dancers had their feet turned inwards, elbows clutched to the sides of their body and their palms held flat, like the wooden idols that were so prominent in Roerich’s mythic paintings of Scythian Russia.’

Nijinsky had been a leading dancer for the Ballets Russes since 1909. His first choreographic enterprise came with L’après-midi d’un faune, based on music by Debussy, which premiered in 1912. This debut choreography proved controversial: among mixed responses to the ballet’s premiere, Le Figaro‘s Gaston Calmette wrote, in a dismissive front-page review, ‘We are shown a lecherous faun, whose movements are filthy and bestial in their eroticism, and whose gestures are as crude as they are indecent’. Nijinsky’s second choreographic work, again after Debussy, was Jeux, which premiered just a couple of weeks before The Rite of Spring.

Nijinsky and Diaghilev had become lovers after first meeting in 1908. In the aftermath of Nijinsky marrying Romola de Pulszky in September 1913, while the Ballets Russes – without Diaghilev – toured South America, Diaghilev fired Nijinsky from his company. He reappointed Michel Fokine as his lead choreographer, despite feeling that Fokine had lost his originality. Fokine refused to perform any of Nijinsky’s choreography. A despairing Stravinsky wrote to Benois, ‘The possibility has gone for some time of seeing anything valuable in the field of dance and, still more important, of again seeing this offspring of mine’.

When Fokine returned to Russia upon the onset of World War I, Diaghilev began to negotiate for Nijinsky to return to the Ballets Russes. However, Nijinsky was in Vienna, an enemy Russian citizen under house arrest, and his release was not secured until 1916. In that year, Nijinsky choreographed a new ballet, Till Eulenspiegel, and his dancing was acclaimed; but he was showing increasing signs of the schizophrenia that would rule the rest of his life, and he retired to Switzerland with his wife in 1917. Without Nijinsky to offer guidance, the Ballets Russes were incapable of reviving his choreography for The Rite of Spring. His choreography was considered lost until 1987, when the Joffrey Ballet in Los Angeles performed a reconstruction based on years of painstaking research. Meanwhile, after the 1913 premiere, Stravinsky would continue to revise his score over the next thirty years.

Nicholas Roerich is perhaps best known today for his own paintings, for his spirituality, and for his cultural activism. His interest in Eastern religion and in the Bhagavad Gita flourished through the 1910s, inspired in part by his reading of the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore. Emigrating to London in 1919, then to the United States in 1920, in 1925 Roerich and his family embarked on a five-year expedition across Manchuria and Tibet. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize several times; while the Roerich Pact – an inter-American treaty signed in Washington in 1935 – established legally the precedence of cultural heritage over military defence. His art and his life is celebrated by the Nicholas Roerich Museum, which holds more than 200 of his paintings, located on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

________

Figes, O. Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (London; Penguin, 2003)

Gibian, G. (ed.) The Portable Nineteenth Century Russian Reader (Penguin, 1993)

Mirsky, D. S. A History of Russian Literature (London; Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968)

With its range of markets – particularly the Saturday and Monday markets on Noordermarkt – and its galleries and shops along Spiegelgracht, there are plenty of opportunities in Amsterdam for buying Japanese prints. Here are three I bought recently:

The first two prints are by Hiroshige, from his series One Hundred Famous Views of Edo (Meisho Yedo Hiakkei), which he completed in the final two years of his life, from 1856 to 1858. The series in fact consists of 119 ukiyo-e prints, plus a title page; print 119 is by Hiroshige II – Hiroshige’s student and adopted son – and it is believed that three other works in the series may have been finished by him. All of the prints were created in the oban tateye format: the ‘oban’ indicating their size of 39cm x 26cm; the ‘tateye’ their portrait orientation.

The series was first published between 1856 and 1859 by Uoya Eikichi, and proved so popular that a deluxe edition soon followed. Vincent van Gogh, who developed a passionate relationship with Japanese woodcuts after moving to Antwerp in November 1885, was especially inspired by One Hundred Famous Views of Edo. His Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree and The Bridge in the Rain (both 1887) were copies after numbers 30 (Plum Park in Kameido) and 58 (Sudden Shower over Shin-Ōhashi bridge and Atake).

The first of the prints above is number 78 in Hiroshige’s series, entitled Teppōzu and Tsukiji Monzeki Temple (‘Shiba Shinmei Zōjōji’). Two sails lead the view across the lively water towards the Hongan-ji Temple, set against a pattern of birds and a pink-purple sky.

The second is number 82 in the series, Moon Viewing (also called Moon Promontory; ‘Tsuki no Misaki’), showing a late evening view over the Edo (now Tokyo) Bay. The vibrant green of the room’s flooring contrasts with the calm water upon which the room looks out; boats are moored, and a full moon rises, crossed by a flock of birds. The remnants of a meal lie on the floor of the room, while a lady changes behind the screen in the corner.

A version of this third print appears in various forms across the internet, most frequently attributed to 1870 and with its creator unspecified. The Library of Congress, for instance, lists a version under the title Owl and magnolia (‘Kobushi ni mimizuku’); noting that its magnolia blossoms are embossed.

The print above is more richly colored, with a green hue, and with its magnolia blossoms a lovely progression of lavender and pink. The V&A Museum reveals it as a work by Kubo Shunman (1757-1820), made around 1800, and an example of surimono – a genre of woodcut privately commissioned for special occasions, and often featuring poems. The given title is Owl on a Flowering Magnolia Branch. Shunman’s ukiyo-e are characterised by such a restrained, subtle use of colour.

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam reopened after seven months a few days ago, 1 May – the culmination of a renovation process which I briefly discussed over at amsterdamarm. The new exhibition which marks the museum’s reopening is entitled Van Gogh at Work, and is the product of eight years of research undertaken by the Van Gogh Museum, the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, and researchers from Royal Dutch Shell. This research has brought various confirmations and some new insights regarding Van Gogh’s working practices, his artistic techniques, and his use of materials. We now know, for instance, that during Van Gogh’s two years in Paris, he bought his canvases from the same shop as his colleague Toulouse-Lautrec; and have gained a sense of the frequency with which he recycled canvases, painting over works or utilising both canvas sides.

The research also extends and establishes our understanding of the way in which some of Van Gogh’s pigments have changed and faded through the course of years. The resulting change in the colour of some of Van Gogh’s paintings is the central theme of articles written about the reopening in The New York Times (‘Van Gogh’s True Palette Revealed‘) and The Guardian (‘Van Gogh’s true colours were originally even brighter‘).

The New York Times piece discusses in particular Van Gogh’s The Bedroom (or Bedroom in Arles). The title refers to three oil paintings: the first painted in Arles in October 1888; the subsequent two painted after the original, in September 1889, whilst Van Gogh was a patient at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, in Saint-Rémy. The New York Times focuses on the initial painting, held by the Van Gogh Museum; and explains that, whilst its ‘honey-yellow bed pressed into the corner of a cozy sky-blue room’ is so familiar to us today, in fact Van Gogh originally painted the walls of the room in violet. The red pigment which he used to mix this violet has faded over time, leaving only the blue. Marije Vellekoop, the Van Gogh Museum’s head of collections, research and presentation, comments, ‘For me, the purple walls in the bedroom make it a softer image. It confirms that he was sticking to the traditional colour theory, using purple and yellow, and not blue and yellow’.

This diminishing of pigment is less evident in the two Saint-Rémy paintings. The second version of The Bedroom, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, shows more intense, cornflower-blue walls. This version is on loan from Chicago for the duration of the Van Gogh Museum’s exhibition, displayed side-by-side with the Arles rendition. The third version of the painting, held by the Musée d’Orsay, bears more trace of the original violet, the colour of its walls approaching lavender.

The emphasis in the New York Times on these particular colour combinations – on violet and yellow becoming blue and yellow – relates to my series on Van Gogh, inspired by the previous collection of his works at the Hermitage Amsterdam. The first piece in that series, published early last month, is titled ‘Gauguin’s Chair and La Berceuse: Conceptualising Red and Green in the Art of Van Gogh‘. The second piece, published at the start of this week, discusses ‘Van Gogh in Paris: The Radicalising of a Palette and a Brush‘. In it, I depict the months he spent in Antwerp, between late 1885 and early 1886, as crucial to Van Gogh’s artistic development. It was in Antwerp that he studied colour theory and began to broaden his palette; inspired as he was upon arriving in the city by the busy, varied life of its docks, and by the Japanese woodcuts he found on sale there.

This, the third piece in my series, considers precisely the occurrence of a violet and yellow contrast becoming a contrast of yellow and blue. Namely, I want to view Van Gogh’s Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, and compare it with Johannes Vermeer’s The Milkmaid.

Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background was one of the last paintings Van Gogh worked on in Saint-Rémy. He completed it in May 1890, before leaving the hospital and moving to Auvers-sur-Oise; where – after achieving dozens more canvases, including his innovative double-square paintings – he would die at the end of July. In marked contrast with the rest of his artistic career, Van Gogh painted relatively few still lifes during his time at Saint-Rémy, painting instead outdoors, in the hospital’s gardens and then in the surrounding countryside. Though he frequently appreciated the order imposed by life at the hospital, and painted prolifically, he continued to experience periods of deep anguish and physical illness.

After suffering what the director of the asylum described as an ‘attack’ on 22 February, Van Gogh kept painting, but wrote few letters over the next two months (he received letters meanwhile from Theo and Gauguin among others; his paintings had recently been shown at Les XX’s annual exhibition in Brussels, and with the Artistes Indépendants in Paris, to the warm acclaim of his fellow artists). This attack motivated his decision, made in early May, to leave for Auvers. Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background was therefore presumably undertaken with his move already firmly in mind. In a couple of letters, Van Gogh writes of working in a ‘frenzy’ during his last few days in Saint-Rémy.

He had completed two studies of irises, out in the garden of Saint-Paul, the previous May, soon after committing himself to the asylum following his time in Arles. Theo greatly admired these, and submitted them to the Société des Artistes Indépendants’ annual exhibition in September. Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background was one of two still lifes with irises which Van Gogh painted a year after these studies. In his own words, in a letter to Theo,

At the moment the improvement is continuing, the whole horrible crisis has disappeared like a thunderstorm, and I’m working here with calm, unremitting ardour to give a last stroke of the brush. I’m working on a canvas of roses on bright green background and two canvases of large bouquets of violet Irises, one lot against a pink background in which the effect is harmonious and soft through the combination of greens, pinks, violets. On the contrary, the other violet bouquet (ranging up to pure carmine and Prussian blue) standing out against a striking lemon yellow background with other yellow tones in the vase and the base on which it rests is an effect of terribly disparate complementaries that reinforce each other by their opposition.

The crisp contours of the leaves and the Japanese-influenced diagonals of the flowers are set against a background which moves thickly around them. Indeed, Van Gogh painted this background last, after the flowers and vase. Yet in the painting as it appears today, the carmine – that pure, rich red which Van Gogh mentions as a facet of it – only faintly remains. As with The Bedroom‘s walls, the violet flowers have turned blue. In this manner, Van Gogh’s art makes explicit the idea that all art is involved in a continual process of becoming. In the particular case of Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, Van Gogh’s painting has become a perfect Vermeer: echoing in its current form Vermeer’s predisposition for the bold and brilliant use of yellow and blue.

Vermeer’s The Milkmaid evinces both this predisposition for colour and his strikingly modern painterly techniques. It was painted around 1668, when Vermeer was just twenty-five years old. In some respects Vermeer is a difficult artist to analyse, for only 34 paintings remain attributed to him, and there is a dearth of material and information relating to his studies and preparatory methods. He appears about 1665 already remarkably accomplished and mature. Broadly, there is something readier, a little rougher, more captured than composed about his earlier works.

Yellow and blue are the dominant colours of The Milkmaid. In the organisation of these, Van Gogh’s Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background appears like The Milkmaid reversed. The distinguishing feature of Vermeer’s palette, when contrasted with those of his contemporaries, was his use of expensive natural ultramarine: this gives his blues here an exceptional vividness, in tune with his similarly luminous handling of lead-tin yellow. Yet the colour combinations in The Milkmaid are complex and various, and not limited to yellow and blue. The contrast in these colours is repeated in the rich contrast between the green of the tablecloth and the maid’s carmine-red skirt.

The same green depicts the milkmaid’s rolled oversleeves, which Vermeer painted alla prima (wet-on-wet), mixing and working the yellow and blue of the maid’s shirt and apron. This method was not uncommon amongst Early and Golden Age Dutch painters: it was adopted by Jan van Eyck and by Rembrandt for several of their compositions. It became a characteristic of many Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, aided by the new availability of pigments in portable tubes, which allowed artists like Van Gogh to go out into nature and paint rapidly en plein air.

A further aspect which links Vermeer to the art of the Impressionists is his use of a pointillé technique – patterns of small dots which, to a modern eye, evoke the pointillism of Seurat and Signac, with which Van Gogh experimented. Collections of small, white dots add texture and suggest the play of light in Vermeer’s painting, noticeable especially on the bread and on the top of the maid’s apron; highlighting also her cap, oversleeves, and the lip of the jug with which she pours. They enhance the atmosphere of softly diffusing light which characterises this brilliant but gentle, boldly restrained, most harmonious of works.