The situation in Crimea continues to develop agallop. Following events in Kiev, unidentified Russian troops have taken control of Crimea’s airports, public buildings, military installations, and ports. Amid claim and counterclaim – the apparent defection of the chief of the Ukrainian Navy, the claimed defection of thousands of Ukrainian armed forces, and allegations that the human rights of UN envoys and journalists are being abused – and with occasional clashes between opposition groups – notably that which took place on 9 March, as the anniversary of the Ukrainian poet Taras Shevchenko was commemorated – a referendum has been scheduled which would decide the region’s future.

Initially proposed for May, brought forward by the Crimean parliament and the city council of Sevastopol (one of two cities – along with Kiev – with special status in Ukraine) to 16 March, the referendum will ask the populace of Crimea whether the region should unify with Russia. The referendum has been declared unconstitutional and therefore illegal by the interim Ukrainian government and by governments throughout Europe and in the United States. For a richer exploration of the contexts involved as the sequence of things shifts and continues in Crimea, it is necessary to provide some detail regarding the wider situation in Ukraine.

Amidst a political background of economic uncertainty and reliance on Russian oil, and with growing allegations of governmental corruption, the protest movement in Ukraine began in earnest on the evening of 21 November 2013. Earlier that day, the Ukrainian parliament had rejected a series of measures which called for imprisoned former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko to be allowed medical treatment abroad; and the Ukrainian government, and President Viktor Yanukovych, issued a decree suspending the signing of an Association Agreement with the EU. This agreement, some aspects of which have been under discussion as far back as 1999, would mean closer political and economic integration between Ukraine and the EU. It includes policy on a ‘deep and comprehensive free trade area’, on visa-free movement between Ukraine and the EU (which at the moment extends only one way, with Ukrainian citizens required to possess a visa to visit EU states), and emphasises the ‘European identity’ of Ukraine.

It is worth noting that the agreement which was to be signed represented a certain amount of progress made during Yanukovych’s Presidency. Attempts towards closer integration had largely stalled under the Presidency of Viktor Yuschenko and the twin governments of Tymoshenko. More, in suspending the signing of the agreement, Yanukovych and the government underneath him – headed by Prime Minister Mykola Azarov – were not explicitly rejecting it, and at first they continued to negotiate with the EU. However, the EU had asked Ukraine to sign the Association Agreement during the EU summit in Vilnius, on 28-29 November. That this would not now occur was taken by many pro-European Ukrainians to indicate the implicit rejection of closer EU ties, in favour of a strengthening of bonds with Russia. Russia had previously indicated that the signing of the Association Agreement would negatively impact Russia-Ukraine trade relations.

Thus, on 21 November, utilising social media and encouraged by several opposition politicians, protesters began to gather at Maidan Nezalezhnosti (‘Independence Square’), the central square in the Ukrainian capital of Kiev, and one which has been used for political rallies since Ukrainian independence in 1991. The number of protesters swelled from 2,000 to as many as 100,000 over the course of the next week, with tensions rising as the Vilnius summit drew to a close: Ukraine had attended, and Azarov continued to assert the government’s desire to reach some deal with the EU, but no agreement had been signed.

Throughout the following two weeks, the protests spread to other cities – notably to Lviv, close to the border with Poland – and began calling for the resignation of the President and the government. Public buildings, including the Kiev city hall, were occupied by groups of protesters. What had began relatively peacefully became increasingly confrontational. The police commenced using batons, stun grenades and tear gas, at first to halt those protesters trying to access governmental buildings, then increasingly to break up all large-scale demonstrations. The police for their part would claim that the protesters initiated these escalations by using tear gas and other explosives. The Azarov government survived a vote of no confidence in parliament on 3 December. On 8 December, the third Sunday of the protests, the number of protesters in Kiev reached at least 500,000; but a few days later the police coordinated their efforts to clear protesters from the Maidan.

Then on 17 December, President Yanukovych and President Putin signed a treaty which saw Russia buy $15 billion of Ukrainian debt, and significantly reduce the price it charged Ukraine for natural gas. The treaty also apparently gave the Russian Navy increased access to the Kerch Peninsula in eastern Crimea. Prime Minister Azarov asserted that the deal had saved Ukraine from potential bankruptcy; while suggesting that the Association Agreement with the EU was still being considered, but some way from being signed. EU ministers stated that the treaty with Russia would not prevent the signing of the Association Agreement; still, the treaty was roundly denounced by the Ukrainian opposition.

Despite this – and despite the attack on Tetiana Chornovol, a journalist and prominent leader of the protest campaign, on 25 December – the protests remained relatively peaceful from the middle of December until the middle of January. On 16 January, a series of draconian anti-protest laws were pushed through parliament. These decreed lengthy jail terms for those engaging in ill-defined ‘extremist activity’, and introduced provisions for the censorship of the internet and social media; and quickly became referred to as the ‘dictatorship laws’. In the aftermath to the passing of these laws, the protests and the response of the authorities intensified. Three protesters were killed between 21-22 January, one shot to death by the police; prominent protest leaders Ihor Lutsenko and Yuriy Verbytsky were abducted, the latter soon found dead; and police began using water cannon on protesters despite the freezing temperatures.

On 28 January, Prime Minister Azarov tended his resignation, which was accepted. He flew first to Austria, later moving on to Russia. In early February, meetings between Yanukovych and leaders of the opposition saw some movement towards compromise and constitutional reform. However, the rhetorical confrontation engaged in by both sides continued apace. On 14 February, the 234 protesters arrested since the beginning of the protests were released from custody; and on 16 February, protesters relinquished their occupation of the Kiev city hall. But on 18 February, around 20,000 protesters began to march on the Verkhovna Rada, the Ukrainian parliament; and in the fighting which followed, with both protesters and the police firing automatic weapons and utilising explosive devices, 20 people were killed with more than a thousand injured. A brief truce held on the evening of 19 February, but the following morning the fighting resumed. With reports of police snipers targeting civilians and leaders of the opposition, a further sixty people were killed, the vast majority from the numbers of the protesters. 21 February saw a deal reached between President Yanukovych and opposition leaders, brokered by the Foreign Ministers of Poland, Germany, and France. Yet this deal too did not hold; Yanukovych fled from Kiev; parliament impeached him and formed an interim government; and the situation in the Crimea began to escalate.

Russia – alongside ministers from Yanukovych’s Party of Regions – has consistently alleged that the violence which has marked the protests has been initiated by the protesters. It argues that the protest movement has been infiltrated by or has contained within and enabled far-right nationalists, quick to adopt violent measures. The symbols and signa of nationalists have been apparent during some of the protest’s fiercest clashes; the Right Sector collective have been implicated in some of the protest’s most critical – and bloodiest – battles. In contrast, the protest movement and opposition leaders have squarely blamed a brutal and reactionary police force for the number of injured and dead; arguing that they were ordered by governmental ministers fighting to remain in power whatever the cost. In particular, the Minister for Internal Affairs, Vitaliy Zakharchenko, has been labelled a criminal for supporting the use of deadly force by the Berkut, the special police force governed by his Ministry. Immediately following the deal struck on 21 February, the Ukrainian parliament voted unanimously to suspend Zakharchenko; also voting to restore the amendments made to the Ukrainian constitution in 2004, which sought to weaken the powers of the President. Zakharchenko’s successor, the acting Minister for Internal Affairs Arsen Avakov, has since dissolved the Berkut.

In tune with their allegations regarding the involvement of far-right nationalists, Russia calls the impeachment of Yanukovych and the formation of a new government illegal, an anti-constitutional coup achieved by force. They point to the cabinet positions the interim government – led by interim Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk – has afforded three protest leaders, along with four members of the controversial nationalist party Svoboda. To the protesters and to the politicians of the opposition, this marks instead the success of a popular uprising, and the deposition of a Presidency and a government who had rendered themselves illegitimate. It could certainly be argued that – disregarding any prior instances of corruption – the grotesque actions of the Berkut were sufficient to delegitimise Yanukovych’s regime. The view of the opposition is the view which appears predominant in Western Europe and North America, and it is the view strongly forwarded by the governments of these countries. One of the problems with this view, however – and preventing any clear delineation of right and wrong – is the apparent lack of political process, the apparent absence of diplomacy, which has marked events in Kiev in the aftermath of 21 February.

The deal signed by Yanukovych and opposition leaders and impelled by the Foreign Ministers of Poland, Germany, and France called for a restoration of the 2004 constitution to prefigure further constitutional reform; the formation of a new unity government; amnesty for protesters arrested from 17 February; and presidential elections to be held no later than December. Yet in the twenty-four hours following its agreement, protesters – who condemned the deal – continued to rally and to occupy public buildings across Ukraine. Police officers abandoned the capital, whether recalled from Kiev to face protests in their home cities, fearful of riots, or refusing to uphold Yanukovych’s position any longer. Presidential buildings became unguarded; Yanukovych hurried to Kharkiv, in the north east of the country; and the Euromaidan protesters entered peacefully and unfettered the governmental buildings of the capital. With around 40 Party of Regions MPs leaving their posts or defecting, and with the tenor in the Verkhovna Rada having fundamentally altered, a new coalition was formed and parliament voted to impeach Yanukovych. Disembodied in the east, Yanukovych responded by asserting the legality of his position as Ukraine’s lawfully elected president, and denouncing events in Kiev as a coup.

Russia had already, during the course of the protests, accused Western governments – particularly the United States – of funding the opposition. But the breakdown of diplomacy immediately following the 21 February agreement increased the sense of Western meddling and Western hypocrisy, and made Russian intervention in some form all but inevitable. Russia undoubtedly perceives the hands of the West behind the ultimate ousting of Yanukovych; and considers that attempts to reach a political compromise were abandoned once the EU and the US saw their preferred outcome emerge via extra-political means. If the West portrays itself as upholding the right for Ukrainians to decide how and by whom they are governed, free from the interference of their often repressively violent and overbearing neighbour, then Russia sees the West acting out of self-interest: heralding and supporting the attempts for independence of those who would seek closer ties with it, while decrying those who would associate with alternative areas of power.

The moral case of the West inevitably implicates democracy as the system of government which best establishes and upholds the rights of the human beings who fall under it. To this supposition, democracy itself must be opened out and questioned, both for its fundamental principles and in its historical development. It is debatable whether modern democracy, as practised in the EU and US, truly allows individuals a significant say regarding how they are governed. This covers a range of concerns, from the lack of choice afforded by too-similar politicians, to revolving door policies and the power of lobbying groups, to the bailout of big banks at the expense of taxpayers, to apparently flawed electoral systems, to a perceived democratic deficit in the governance of the EU.

A notable facet of modern democracies appears to be how efficiently they stifle protest – at an ideological level, before it comes to the legal restrictions placed upon the right to protest and excessive policing of those protests which do take place. Protesters in modern democratic societies are routinely cast and outcast as dangerous and extremist regardless of the specificities of their views. Little over a week ago, 1,000 environmental protesters protested peacefully outside the White House in Washington, over the controversial fourth phase of the Keystone oil pipeline project. 400 of these protesters were arrested, their appeals dismissed as constituting ‘an extreme position…well outside the American mainstream’. De Tocqueville warned of the ‘soft despotism’ inherent in the democratic system, and always to be considered and guarded against:

‘Thus, after having thus successively taken each member of the community in its powerful grasp and fashioned him at will, the supreme power then extends its arm over the whole community. It covers the surface of society with a network of small complicated rules, minute and uniform, through which the most original minds and the most energetic characters cannot penetrate, to rise above the crowd. The will of man is not shattered, but softened, bent, and guided; men are seldom forced by it to act, but they are constantly restrained from acting. Such a power does not destroy, but it prevents existence; it does not tyrannize, but it compresses, enervates, extinguishes, and stupefies a people, till each nation is reduced to nothing better than a flock of timid and industrious animals, of which the government is the shepherd.‘

Nor can the recent history of Russian-Western relations beyond Ukraine and Crimea be dismissed. Russia can justifiably mock US Secretary of State John Kerry’s assertion that ‘You just don’t in the 21st century behave in 19th century fashion by invading another country on completely trumped up pretext’, given the invasion of Iraq – which Kerry voted for – based on alleged but nonexistent weapons of mass destruction. Meanwhile, the West’s analysis of the ongoing conflict in Syria seems increasingly open to debate. One prominent study of rocket trajectories argues that the rockets which delivered sarin gas to Ghouta, near Damascus, last August could not have been fired from within areas controlled by the Syrian government.

Thus Russia’s engagement in Crimea implicates Russian concern over Western influence, Western sleight-of-hand, and a breakdown in diplomacy; it has been encouraged by some of the protest movement’s association with aspects of the far-right; and it reflects Russia’s dislike of Ukraine’s change in political regime, as well as a perception that the Ukrainian political class is disorganised, self-absorbed, backed by various competing oligarchs, and incapable of providing the stability that could be conducive to its purposes as well as to the Ukrainian populace. Reading between the lines, there is a sense that many Ukrainian citizens would welcome close cooperation with both Russia and the EU, for economic and cultural reasons; but the more the situation in the country escalates, the more they are forced to pick sides. One of the reshaped parliament’s least helpful measures was its overturning, on 23 February, of a minority languages law, which allowed Russian to function as an official second language in those regions with a sizeable Russian population.

What Russia desires as the result of its excessively militarised response remains unclear. The annexation of Crimea is presumed, based upon the example set in Georgia, but any serious attempt towards this end would be met with international opposition: there would undoubtedly be sanctions, and a serious deterioration in Russia’s international relationships. Russia would have much to lose by perceived annexation: without the ethnic Russian population of Crimea to balance opinion in the west, and in response to such an outcome, Ukraine could slip decisively, electorally and ideologically, from its powers of influence. Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, founded along with the city of Sevastopol in 1783, is now small and old and in need of modernisation; but access to the Black Sea from Crimea remains a strategic and economic imperative for Russia. In 1997, a partition treaty divided the Black Sea Fleet and effectively formed the Ukrainian Navy; as part of the treaty, Russia was ensured military access to Crimea, and the base of its fleet in Sevastopol, until 2017. In 2010 this agreement was extended until 2042. According to its terms, Russia are allowed to station 25,000 troops on Crimea – more than the 16,000 which Ukraine claims are currently present – but, of course, these troops are not allowed to assert themselves off base and unidentified. It is plausible that Russia is endeavouring to secure primarily its military access to the region. At this point in time, any further excursions appear as unlikely as they would be unwarranted.

More than a swift reaction to recent political events, Russia’s intervention in Crimea must be read from a longer cultural and historical perspective. The broader response from the populace of Crimea to the protests in the west of the country must equally be viewed not merely within their immediate context – portrayed in opposition to the protesters’ successes in Kiev – but with an understanding of the Crimea’s own highly distinct history and culture. The trajectory of the Crimea does not merely parallel or diametrically oppose what is happening elsewhere in Ukraine: it has unique roots and currents.

The short history of Crimea as part of Ukraine began on 19 February 1954, when the Crimean Oblast was transferred from the authority of Soviet Russia to the authority of Soviet Ukraine. The rationale behind this transfer remains a subject of debate: some have considered it essentially a gift, marking the 300th anniversary of Ukraine as part of the Russian Empire; others have stressed the close cultural, economic, and practical links between the region and the Ukrainian mainland. In January 1991, Crimea was upgraded from an Oblast to an Autonomous Republic. Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, it remained part of independent Ukraine, with much autonomy and its own parliament. Across 1992 the Crimean parliament agreed to retain unity with Ukraine, but only after securing even greater autonomy from Kiev; in May, the parliament also established a Crimean constitution.

In October 1993, the Crimean parliament established the post of President of Crimea. At the same time, it agreed upon parliamentary representation for Crimea’s Tatars: the Crimean Tatars were given 14 seats in the body of 100, despite their protests that Crimea should not possess a president distinct from the President of Ukraine. After a pro-Russian President of Crimea was voted into power in 1994, in March 1995 the Ukrainian parliament unilaterally abolished the post and scrapped the Crimean constitution. A new constitution was formed and finally ratified by the Ukrainian parliament in 1998; while the treaty of friendship of 1997 regarding the division of the Black Sea Fleet calmed differences between Kiev and Moscow concerning the region.

————

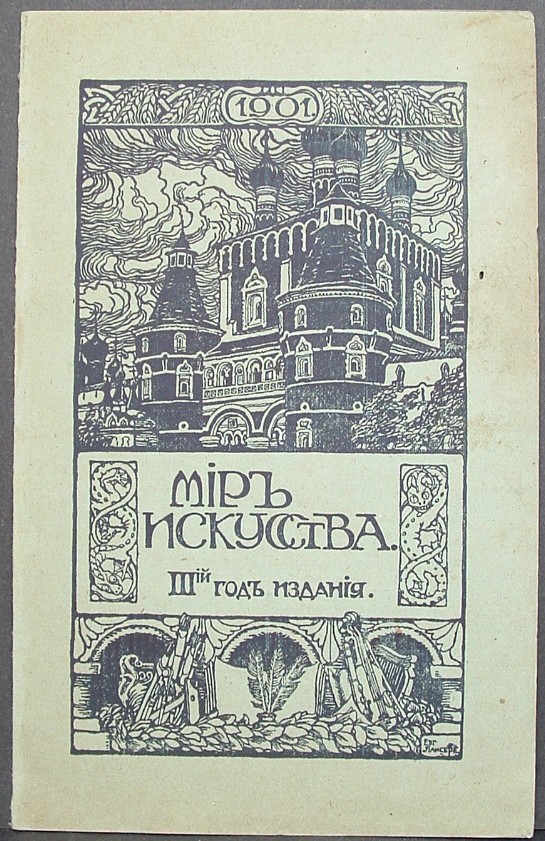

For those who desire a retreat from such densely political frontiers; who would extend their political understanding via other contexts; or else derive pleasure or relaxation through incidental knowledge – what follows is the long history of Crimea, seen through the eyes and down the nibs of some of the great men of Russian letters. It is a political history, a cultural history, and a literary history.

Kievan Rus flourished from about 882 – when Prince Oleg moved the capital of the Rus from Novgorod to Kiev – until the 13th century, when the Mongol Empire invaded and destroyed their major cities. While Russia gradually threw off the ‘Mongol-Tatar Yoke’, and began to emerge round the city of Moscow as a powerful independent state, Kiev and much of what is now northern and central Ukraine came under Polish-Lithuanian control. The Russo-Polish War of 1654-1667 ended in a truce, but one which forced the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to relinquish Kiev and the lands east of the Dnieper River (plus Smolensk further north) to the Tsardom of Russia. These lands continued to rule themselves with some autonomy for the next hundred years, the period of the Cossack Hetmanate; but this autonomy was successively diminished during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762-1796), and the region came to be fully incorporated into the Russian Empire. Russia often considers the union between Kiev and Moscow to extend back to the beginnings of the the Russo-Polish War in 1654.

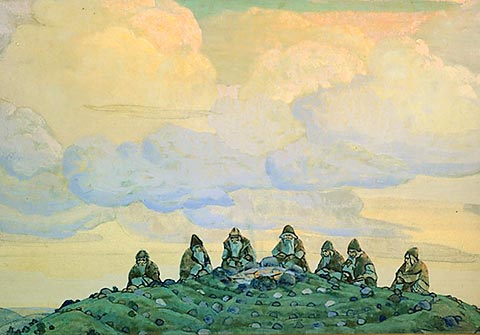

The history of Crimea is distinct from the history of Kiev and mainland Ukraine. The region passed through the firm and fragile hands of the Cimmerians, Greeks, Bulgars, and Kievan Rus, among hordes of others, before the 13th century, when it became implicated in the Venetian-Genoese Wars, between the rival Republics of Venice and Genoa. The Republic of Genoa ruled Crimea for two centuries, its rule authorised by the Golden Horde which had fragmented from the Mongol Empire. As the Golden Horde itself began to fragment and dissolve, Tatars who had settled in the region came to power and established the Crimean Khanate in 1441. This Crimean Khanate, ruled by Crimean Tatars, came under Ottoman rule in 1475, but functioned as a protectorate, with significant autonomy from the Ottoman Empire.

The Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774 resulted in a decisive victory for Russia. It annexed the area of land which is now southern Ukraine; and while the Crimean Khanate became nominally independent, in reality it came under Russian control and was annexed in 1783. Thus by the late 1700s, all of modern Ukraine was part of the Russian Empire. The lands of southern Ukraine and Crimea were referred to as Novorossiya (‘New Russia’), and many of the region’s prominent cities were founded at this time: including Sevastopol in 1783, and Simferopol a year later, both in Crimea; and further north-west, on the mainland overlooking the Black Sea, Odessa in 1794.

Odessa grew rapidly, governed in its early years by the Duc de Richelieu, becoming a free port in 1819, and emerging as a truly multinational and multilingual city: Italian was the lingua franca, spoken alongside Russian and French (Binyon, 154). Pushkin, exiled from Saint Petersburg for writing revolutionary epigrams, spent several months in the Caucasus and Crimea in 1820. He joined the company of General Nikolay Raevksy, famous for his feats on Russia’s behalf during the Napoleonic Wars; and Pushkin formed enduring friendships with Raevsky’s sons and daughters. According to D. S. Mirsky, these months, ‘spent in the company of the Rayévskys…were one of the happiest periods of Pushkin’s life. It was from the Rayévskys also that he got his first knowledge of Byron’ (Mirsky, 81). Then, between exiles, Pushkin would spend a year in Odessa from July 1823 until July 1824. The period was particularly fruitful for his work. He had begun writing Eugene Onegin in May, and completed most of the first three chapters, including Tatyana’s letter, in Odessa. Meanwhile, he published the narrative poem The Fountain of Bakhchisaray; and Odessa also proved the source for a number of his greatest love lyrics. Personal intrigue and the proclamation of atheism in one of Pushkin’s letters was enough for the authorities to force Pushkin’s departure from Odessa; he spent the next two years at Mikhailovskoe, his family estate near Pskov.

The Crimean War (1853-1856) would come to centre upon Sevastopol, after impacting Odessa along with many of the major Russian and Ottoman cities by the Black Sea. The war may be perceived as a culmination of the Russo-Turkish wars of the previous three centuries. Provisionally, it was the result of a series of political intrigues concerning the status of Christianity in Palestine, which was then controlled by the Ottomans. Ever since the fall of the Byzantine Empire, Russia had considered itself the protector of the Eastern Orthodox Christian faith. The see of Moscow had been accepted as an Orthodox patriarchate in 1589; though rather than taking the traditional place of Rome as the first patriarchate, it was listed fifth, behind the patriarchates of Constantinople, Antioch, Alexandria, and Jerusalem. One of the consequences of the Russo-Turkish War of 1768-1774 had been the assertion of Russia’s right to protect all Orthodox Christians under Ottoman rule. Roman Catholic France, during the reign of Napoleon III, sought to alter this state of affairs, and began to negotiate with the Ottoman Empire demanding that it be given power over the Christian peoples and places of Palestine.

After the Ottoman Empire initially upheld the position of Russia, France undertook a show of force, sending the warship Charlemagne to the Black Sea. Cowed by the superior naval capacity of the French, the Ottomans ceded to their demands, allowing France and the Roman Catholic Church authority over Christianity in Palestine, and reverting to Latin an inscription at the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem, symbolically placing it under French control. Attempts towards a diplomatic resolution made little progress, and the Russian Empire responded by sending soldiers through Moldavia and Wallachia (regions of modern-day Moldova and Romania), and to the Caucasus, which it was in the long process of annexing. (Lermontov was twice exiled as an officer to the Caucasus, and depicted the region in his novel A Hero of Our Time, published in 1840, in the middle of the Caucasian War). With both the Russians and the Ottomans also building their fleets in the Black Sea, this first phase of the Crimean War reached a climax with the Battle of Sinop. Sinop, historically called Sinope, was itself the birthplace of important writers, philosophers and theologians: Diogenes of Sinope is noted as the founder of philosophical Cynicism, and his witticisms, bold manners, and frequent quarrels with Plato are amusingly recounted in Diogenes Laertius’s Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers; Aquila of Sinope completed a translation of the Old Testament into Greek, the influence of which was recognised ans assured when Origen included it as part of his Hexapla: and Marcion of Sinope was ultimately declared a heretic for his rejection of the God of the Old Testament, but his writings encouraged the formation of the New Testament biblical canon. The battle which took place in the waters of Sinop in November 1853 saw Russian warships attack an anchored Ottoman patrol force, and come away with a significant victory.

This forced the hand of the French and the British, both of whom desired to prevent the expansion of the Russian Empire into the weakening Ottoman state. In March 1854, both declared war on the Russian Empire. By September, the focus of the war had turned to Crimea, and the allied forces of the French, British and Ottomans laid siege to Sevastopol, Crimea’s largest city and home to the Russian Empire’s Black Sea Fleet. Battles were fought in nearby towns and ports, and Sevastopol was repeatedly bombarded by the allies; despite the death of the Russian Emperor Nicholas I in March 1855, the Siege of Sevastopol persisted throughout the year, until the Russian forces withdrew the following September.

The fall of Sevastopol meant Russian defeat in the Crimean War. The Treaty of Paris, signed in March 1856, saw the Russian Empire return land to the Ottoman Empire, and relinquish all claims to the Danubian Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which became independent. France won authority over the Christian peoples of the Holy Land. Crimea – which had been devastated, and seen the departure of much of its population – was restored to Russian control, but the Black Sea was declared a neutral territory, diminishing the Russian Empire as a military force. The failed war effort had also hurt the Empire economically, and the practical and psychological ramifications had far-reaching consequences: they encouraged the Alexander reforms of the 1860s, where Alexander II – Nicholas I’s son and successor – emancipated the serfs, and later reformed the Russian judiciary and military; and they impelled the sale of Alaska to the United States in 1867, with Russia struggling for funds and fearing they may lose the region without recompense in future military engagement.

Tolstoy had travelled to the Caucasus in 1851, and was motivated to sign up for the Russian army, serving in the same artillery regiment as his brother Nikolay. For two and a half years he participated in the Caucasian War; he was based in modern-day Chechnya. It was during this period that he began in earnest his artistic career: he completed, and saw published in The Contemporary, his first novel Childhood; wrote and published his second novel Boyhood; and in between published his first short story, ‘The Raid’, a realistic portrayal drawing upon his experiences in the region. In 1853, he attempted to resign from the army, but as an officer, his resignation was refused owing to the onset of the Crimean War.

So Tolstoy became an active participant in the Crimean War, serving in Bucharest from March 1854, then in November travelling to Odessa, then on to Sevastopol, where he was to be based for the next year. He began work on Youth, the final novel in his autobiographical trilogy; and wrote three reports on the war, ‘Sevastopol in December’, ‘Sevastopol in May’, and ‘Sevastopol in August’. ‘Sevastopol in December’ was published in June in The Contemporary. While his first two novels had resulted in literary acclaim, this first piece of war reportage brought Tolstoy a wider reputation across Russia. ‘Sevastopol in May’, a harsher, bleaker, and anti-militaristic depiction of the war, was butchered by the censor. The three texts would be published as the Sevastopol Sketches after the war had ended; together, they comprise Tolstoy’s claim to being the first modern war correspondent (an accolade often bestowed upon William Howard Russell, who covered the Crimean War for The Times). The Siege of Sevastopol would provide another first within the realm of Russian art and letters: Defence of Sevastopol was the Russian Empire’s first feature film, premiering at the Livadia Palace in Crimea in October 1911. The Livadia Palace near Yalta, a summer estate of the Russian Emperors from the 1860s, rebuilt by Nicholas II, would host the Yalta Conference towards the close of World War II.

Numerous biographers depict Tolstoy’s year in Sevastopol as decisive for his personal and artistic development. Both Henri Troyat and Rosamund Bartlett cite a diary entry he made in March:

‘Yesterday a conversation about divinity and faith led me to a great and stupendous idea, the realisation of which I feel capable of devoting my whole life to. This idea is the foundation of a new religion corresponding to the development of mankind – the religion of Christ, but purged of dogma and mystery, a practical religion, not promising future bliss but providing bliss on earth. I realise that to bring this idea to fruition will take generations of people working consciously towards this goal. One generation will bequeath this idea to the next, and one day fanaticism or reason will implement it. Working consciously to unite people with religion is the foundation of the idea which I hope will occupy me.‘

Bartlett comments that, ‘In a sense all of Tolstoy’s future career is here, as he was always a religious writer, concerned with seeking the truth. In his early works this concern was implicit, but it became increasingly explicit as he evolved as an artist’. Troyat writes, ‘The whole of Tolstoy’s future doctrine is summed up in these few lines scribbled in his notebook: refusal to submit to Church dogma, return to early Christianity based on the Gospels, simultaneous search for physical well-being and moral-perfection…The time was undoubtedly not yet ripe for a full spiritual flowering. But a slow process of fermentation had begun, deep within this unquiet soul, a subterranean and painful preparation for apostolate…in the state of perpetual mental upheaval which he lived, one idea remained constant: write’.

Tolstoy’s perspective on ‘the religion of Christ, but purged of dogma and mystery’ reverberates in the works of Dostoevsky, particularly in the Grand Inquisitor passage from The Brothers Karamozov. Tolstoy’s religious and ethical views, his Christian anarchism, his pacifism, and his focus on man’s relationship with the land, would also profoundly influence foreign thinkers, including Wittgenstein and James Joyce. Still, other historians view the decisive impact of Sevastopol upon Tolstoy in material rather than spiritual-artistic terms.

Tolstoy remained at this point in his life a fervent gambler and womaniser. Orlando Figes recounts, ‘In 1855 Tolstoy lost his favourite house in a game of cards. For two days and nights he played shtoss with his fellow officers in the Crimea, losing all the time, until at last he confessed to his diary ‘the loss of everything – the Yasnaya Polyana house. I think there’s no point writing – I’m so disgusted with myself that I’d like to forget about my existence’. Much of Tolstoy’s life can be explained by that game of cards. This, after all, was no ordinary house, but the place where he was born, the home where he had spent his first nine years, and the sacred legacy of his beloved mother which had been passed down to him’. Tolstoy returned to Yasnaya Polyana towards the end of May 1856, after several months in Saint Petersburg and Moscow. With the family house sold and dismantled to pay his debts, he lived in one of the remaining wings and, ‘as if to atone for his sordid game of cards, he set about the task of restoring the estate to a model farm’. Tolstoy would continue at Yasnaya Polyana for the remainder of his life, leaving just over a week before his death in the stationmaster’s house at Astapovo; he was buried at Yasnaya Polyana, amid thousands of mourners, in a treasured spot of the woods by his home.

The Crimean War had also seen the allied forces lay siege to Taganrog, a port city on the Sea of Azov, in the Rostov region of Russia which borders modern Ukraine. Taganrog withstood the siege by British and French forces between June and August 1855, though it suffered significant damage; consequently, the city was exempted from taxes in 1857. In 1860, Chekhov was born in Taganrog. When he was diagnosed with tuberculosis in 1897, he was required to seek warmer climes than those of Moscow or Melikhovo, the estate twenty miles south of Moscow where he had lived since 1892. So at the end of August 1899, Chekhov sold Melikhovo and moved to Yalta, where he had built a villa. East of Sevastopol and overlooking the Black Sea, since the Crimean War Yalta had emerged as the most popular resort within the Russian Empire. Chekhov was not overly fond of Yalta, which he called a ‘hot Siberia…there is nothing here to interest me’; and he bemoaned the tendency of Russian doctors to proscribe time in Crimea for anyone suffering the slightest cough. He would have preferred to return to Taganrog, but the city did not have an adequate water supply. Still, Chekhov lived in Yalta until June 1904 when, his health deteriorating, he travelled to the spa town of Badenweiler in Germany, dying there the following month.

In Yalta – aside from receiving visitors, and spending some time with Tolstoy, who stayed at nearby Gaspra between 1901 and 1902 – Chekhov wrote his two final plays, Three Sisters and The Cherry Orchard. Both were written for the Moscow Art Theatre, who produced them under the direction of Constantin Stanislavski. Chekhov wrote the part of Masha in Three Sisters specifically for Olga Knipper, a leading actress with whom Chekhov had corresponded since she appeared in The Seagull in 1896. The pair would marry in May 1901. Also in Yalta, Chekhov wrote some of his greatest short stories, including ‘In the Ravine’ and ‘The Lady with the Little Dog’. The latter begins in Yalta: a middle-aged man and a young woman, both married but visiting alone, meet there and become lovers. They return to their different lives, but eventually begin meeting secretly in Moscow. They talk to each other, they feel that they are in love, and the story ends:

‘And it seemed as though in a little while the solution would be found, and then a new and glorious life would begin; and it was clear to both of them that the end was still far off, and that what was to be most complicated and difficult for them was only just beginning.‘

Nabokov described Chekhov’s story: ‘All the traditional rules of story telling have been broken in this wonderful short story of twenty pages or so. There is no problem, no regular climax, no point at the end. And it is one of the greatest stories ever written’.

Nabokov’s father would be a key figure during the next tumultuous period in Crimea’s history, as the Russian Empire succumbed to revolution and civil war. The February Revolution of 1917, centred on Saint Petersburg – which had been rechristened Petrograd during World War I, an attempt to remove all vestiges of German from the name – and in fact emerging out of protests to mark International Women’s Day, resulted in the abdication of Nicholas II, who had lost popular, political, and military support. He named the Grand Duke Michael, his brother, as his successor, but the political situation was not conducive for any succession, and Michael declined to accept until the formation of an elected Constituent Assembly, which could approve his role. It was Nabokov’s father, Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov, who wrote Michael’s abdication letter; and in the Provisional Government which formed under Alexander Kerensky in the absence of a ruler, Vladimir Dmitrievich served as secretary.

Kerensky’s government was progressive, but struggled to assert a new political structure. It made numerous missteps of its own; angered the populace by refusing to withdraw from the war; and suffered fierce opposition, from the Petrograd Soviet within the capital, and from the Bolsheviks further afield. It fell in the October Revolution of 1917 which saw the Bolsheviks seize power. Vladimir Dmitrievich would later write an important memoir of this period, entitled The Provisional Government. More immediately, Nabokov’s family were forced to hurry from Petersburg, and they moved to Crimea. Nabokov’s biographer, Brian Boyd, summarises the political climate:

‘Three main political currents swirled around the Crimea late in 1917: the Socialist Revolutionary influence dominant in the countryside and in the local zemstvos; the nationalism of the Tatars, one-third of the population, who during the power vacuum of 1917 had set up their own parliament to administer Tatar affairs; and the anarchism of the sailors and soldiers in the port cities, especially Sebastapol, headquarters of the Black Sea fleet. While most of the unruly sailors at Sebastapol felt themselves full of revolutionary spirit, they had little inclination to Bolshevism until heavily armed Baltic sailors were dispatched from Petrograd late in the year. A takeover of the Sebastapol Soviet in December gave Bolsheviks power in the city and set in motion the first of the region’s massacres (more than a hundred officers killed). Elsewhere the Crimea was calm, with Tatar military detachments holding the area around Simferopol.‘

It was these Tatars, making up around a third of the population in late 1917, and setting up their own government – the Crimean People’s Republic, which lasted for only one month between December 1917 and January 1918, but may be considered an attempt to form the first secular Muslim state – who would be forcibly deported from the region during World War II. The Soviet Union under Stalin accused the Crimean Tatars of collaborating with the Nazis, and the population of 200,000 were deported, the vast majority to the Uzbek SSR. It is thought that 46% of these people died during deportation. The Tatars only began returning to Crimea during the 1980s; today, they comprise around 250,000 of the region’s population of just over two million.

Staying at Gaspra, the Nabokov family initially sought to stay out of current affairs, Vladimir Dmitrievich’s political past making him vulnerable to arrest or worse. As the Russian Civil War progressed and the Bolsheviks endeavoured to assert themselves in Crimea, World War I continued, German troops advanced and, in late April 1918, occupied the region. This was a welcome relief for much of the populace, a respite from the tension and potential bloodshed of the Bolsheviks clashing with their opponents. Crimea became a relative stronghold of the opposition, and authority in the region would pass between the Bolsheviks and their opponents over the next few years.

When the Germans withdrew from Crimea and the puppet government they had installed fell in November 1918, the Crimean Regional Government formed under Solomon Krym. This Crimean Regional Government was opposed to the Bolsheviks, but was not closely allied to the White Army, drawing its members from both socialists and non-socialists, and concerned with the specifics of the local situation. Vladimir Dmitrievich Nabokov became the government’s minister of justice, and served until April 1919 when, weakened by its differences with the White Army, the Bolsheviks again seized power. Nabokov’s family were again forced to depart, and they eventually made their way, through Greece, to England, where Nabokov would study at Cambridge. Crimea would become the site of the last stand of the White Army: the defeat of the White Army, under the command of General Wrangel, in November 1920 effectively marked the end of the Russian Civil War. The Crimean Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic was formed a year later, and converted to the Crimean Oblast, fully part of Soviet Russia, in 1945. Nabokov’s father Vladimir Dmitrievich died in Berlin in March 1922, shot in the process of defending one of his liberal political rivals from far-right gunmen.

————————

For the political overview of this piece, I have used a variety of news sources – including Reuters, the BBC, The Guardian, The New York Times, Foreign Policy, Slate, and RT; online encyclopedias, notably Wikepedia; and each of the books listed below.

A selection of sources:

The BBC’s timeline of the Ukrainian crisis: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-26248275

A depiction of the role of the far-right in the protest movement: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-26468720

A New York Times piece on the fall of Yanukovych: http://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/24/world/europe/as-his-fortunes-fell-in-ukraine-a-president-clung-to-illusions.html

RT’s response to the interim Ukrainian government’s cancellation of the minority languages law: http://rt.com/news/minority-language-law-ukraine-035/

‘Facts you may not know about Crimea’: http://rt.com/news/russian-troops-crimea-ukraine-816/

On the arrest of Keystone pipeline protesters in Washington: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/03/us-usa-keystone-protest-idUSBREA210RI20140303

A study suggesting that chemical weapons used in Syria could not have been fired from within areas controlled by the Syrian government: http://www.mcclatchydc.com/2014/01/15/214656/new-analysis-of-rocket-used-in.html

An opposing perspective: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/06/sarin-gas-attack-civilians-syria-government-un

Literature:

Rosamund Bartlett Chekhov: Scenes from a Life (Free Press, 2005)

Rosamund Bartlett Tolstoy: A Russian Life (Profile Books, 2010)

T. J. Binyon Pushkin: A Biography (New York: Vintage, 2002)

Brian Boyd Vladimir Nabokov: The Russian Years (London: Vintage, 1993)

Anton Chekhov Selected Stories of Anton Chekhov (trans. R. Pevear & L. Volokhonsky) (Modern Library, 2000)

R. F. Christian (ed.) Tolstoy’s Diaries (London: Flamingo, 1994)

Norman Davies Europe: A History (Pimlico, 1997)

Orlando Figes Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (Penguin, 2003)

D. S. Mirsky A History of Russian Literature (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968)

Vladimir Nabokov Lectures on Russian Literature (Harcourt, 1981)

Henri Troyat Tolstoy (Penguin, 1980)

![Pierrot and Harlequin [Mardi-Gras] (1888-1890) - Paul Cezanne - Gallery of European and American Art - Moscow Musts](https://culturedallroundman.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/cezanne-pierrot-and-harlequin.jpg?w=467&h=580)