In early April, I began a series on the art of Vincent van Gogh. Propelled by a thematic display of his works at the Hermitage Amsterdam, my series continued on as these works were removed and transported back across the city for the reopening of the Van Gogh Museum, on 1 May, and with a new exhibition, entitled Van Gogh at Work.

The first piece in my series centred on psychological interpretations of the use of red and green in a number of Van Gogh’s paintings: Gauguin’s Chair, La Berceuse, and The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital. The second piece provided an overview of Van Gogh’s early artistic career, through Brussels, Etten, The Hague, and Nuenen, before viewing the emboldening of his art during the time he spent in Antwerp and Paris. The third piece considered new research undertaken by the Van Gogh Museum into Van Gogh’s artistic practices and use of pigments; and compared his Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background with Vermeer’s The Milkmaid. So in turn these three short essays saw Van Gogh in Arles from late 1888 to the spring of 1889, prior to his installation in the asylum at Saint-Rémy; in Antwerp from late 1885 to early 1886, then in Paris over the next two years; and towards the very close of his year in Saint-Rémy, just as he was about to move on to Auvers-sur-Oise.

It is rare that any endeavour is completed – so many of our tasks are cyclical, looping, or intermittently repeating; and work started upon tends to encourage more ideas, to bring about new prospects, to demand ever-more work. This piece in my series draws from the research and the concerns of the others, and views Van Gogh during his early days in Arles, in the spring of 1888. Van Gogh left Paris for Arles in February. Just as he moved from Antwerp to Paris struggling with ill health – the effects of an insufficient diet, and excessive drinking and smoking – so the move further south was made with Van Gogh ill and seeking a kinder climate. More, he had become exhausted with life in Paris, and sought for his art to be reinvigorated by Arles’ light and its exotic atmosphere.

Though he had become close with Paul Signac living in Paris, and had experimented with pointillism, Van Gogh met Georges Seurat for the first time only in the hours before his departure from the city. Vincent arrived in Arles on 20 February. He found the town under a cover of snow; and began staying in accommodation at the Restaurant Carrel. Immediately setting about his work, between the beginning of March and the end of April he completed fifteen paintings of trees and orchards in blossom. These were prefaced by two still life studies, ‘Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass’ and ‘Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass with a Book’: the movement between indoors and outdoors, between still life paintings and painting en plein air, was always a fluid movement for Van Gogh; and he kept objects and themes in mind, dwelling on them in sustained short bursts, often returning to them in the longer term.

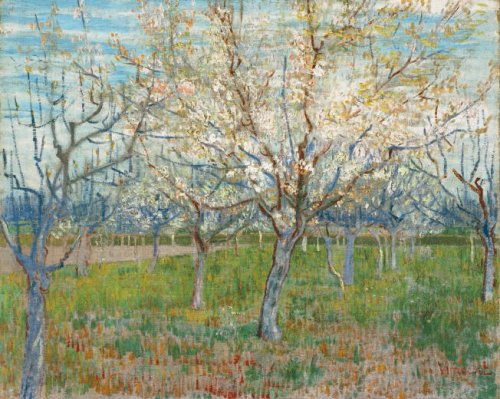

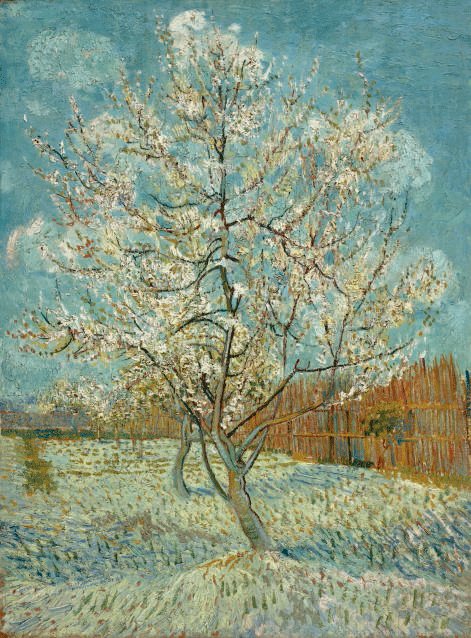

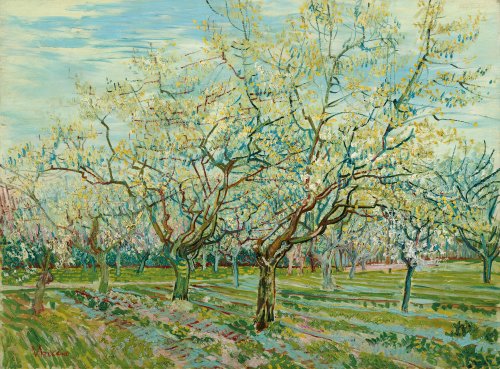

Of the fifteen blossoming orchard scenes he completed, three stand out because, in a letter to Theo on or around 13 April, Vincent explicitly tied them together as a triptych. These are The Pink Orchard (also known as Orchard with Blossoming Apricot Trees), The Pink Peach Tree (or Peach Tree in Blossom), and The White Orchard. Vincent included in his letter a sketch of this triptych. He was increasingly fond of linking his works in such a way, and would later envision his Sunflowers in triptychs, one either side of a La Berceuse. While stating his desire to paint repetitions of his blossom paintings, and his hope to complete at least nine canvases in total – with the implication that these nine canvases would divide into three triptychs – we have no information regarding which of the other finished paintings Vincent may have intended to go together.

In fact, even Vincent’s ink-sketch is not decisive: The Pink Peach Tree is almost identical in composition with The Pink Peach Tree (Souvenir de Mauve), which was the second painting in the blossom series, completed just after The Pink Orchard (The Pink Orchard and Souvenir de Mauve were the first two paintings in the series, from March; whereas The Pink Peach Tree and The White Orchard were the last two, finalised towards the end of April). We can conclude that The Pink Peach Tree is the painting Van Gogh conceived for the triptych because, in a letter to his sister Willemien on 30 March, he expressed his intention to send the earlier painting to the widow of Anton Mauve. Mauve was Vincent’s cousin-in-law and had been an important figure in Van Gogh’s early artistic development; Vincent sent Souvenir de Mauve to Theo in May, and it was subsequently passed on to Mauve’s widow Jet.

Together, the three paintings of the triptych show Van Gogh developing upon the techniques and inspirations of his time in Paris. There is the bold use of vivid colour; and the influence of ukiyo-e Japanese prints evident in his cropped, asymmetrical compositions and his rhythmic lines and contours. In fact, Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige), from the autumn of 1887, is a distinct precursor to the series.

Just as in some of his later paintings – including The Bedroom, painted in Arles in October 1888, and Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, painted in May 1890 in Saint-Rémy – the canvases here too demonstrate the diminishing of red pigment over time, for the pink blossom which was present in the first two paintings of the triptych, as indicated by their titles, has faded and become predominantly white.

In The Bedroom and Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, Van Gogh would mix red pigment with blue to arrive at violet-purple. Contrasting this purple with a range of yellows, Van Gogh was thereby remaining true to traditional colour theory, which he had studied in Antwerp. As the red pigment which he utilised has faded, the palette of these two paintings has changed from yellow-purple to yellow-blue; two colours which, while not strictly opposing on the colour-wheel, remain highly complementary. The disappearance of so much pink in Van Gogh’s blossom paintings perhaps represents, therefore, a greater change to the nature of these works and the way they are viewed and considered. With the red pigment’s absence leaving only the white behind, these works take on a luminous, spiritual quality.

The Pink Orchard well demonstrates the range of painterly techniques which Van Gogh had by this point developed. It features short brushstrokes of red and green for the grass in the foreground, painted thinly and with the canvas showing through – characteristics of some of his paintings of Parisian streets and gardens in Montmartre. Its trees rise in tones of ultramarine, with blue contour lines and bare branches. The composition moves diagonally, from the near left to the far right; this was the first blossom painting Van Gogh painted, early in the season after a long winter, and many of the trees are not in bloom; the handful of trees in the centre which are blooming show flowers painted in impasto, now predominantly white, but with highlights of pink and orange. Set against the contours of the trees and a light-blue, almost turquoise sky, which moves horizontally behind the branches, the painting divides loosely into two colour contrasts: the red/green of the ground, and the blue/oranges of the sky above.

The Pink Peach Tree shows an impasto application of paint throughout, with flowers painted so thickly that they all but hang from the canvas. The central colours here are in the white of the ground and the blossom, in their green highlights, and in the thick blue-turquoise sky painted and suspended around the blossom flowers. The fence to the right of the composition is painted in long verticals and with a diversity of colours again reminiscent of Van Gogh’s 1887 Montmartre paintings; its oranges, browns and reds offset the central, titular, sky-bearing tree, and juxtapose with the lower greens and upper blues.

The White Orchard is the most evenly painted of the three works, and appropriately the one with the least pink in the blossom of its trees. Their white and green blossom, resting upon blue branches, is counterbalanced by the pinks and purples – in fact, mauves – which highlight the ground. This orchard appears in full blossom, the branches of its trees entangling against a delicate sky.

The popular conception of Van Gogh often seems one of a headstrong, difficult and solitary artist; whose relationships with the opposite sex were ill-conceived and ultimately short-lived; who concluded perhaps the most famous co-habitation in the history of art by cutting off his own ear; who went unrecognised in his lifetime; and who died alone in Auvers-sur-Oise. The difficulties he had within specific relationships cannot be denied, and that there was a strong solitary strain to his personality is also clear. In October 1876, years before he embarked upon his artistic career, in a Methodist church in Richmond, England, Van Gogh delivered his first sermon, and opened with the belief ‘I am a stranger on the earth’. Yet this sense of Van Gogh alone does not account for the complexities of his personality, or for the connections he sought and the very real connections he made.

In Paris, Van Gogh became acquainted with Émile Bernard, with whom he began corresponding, especially during his time in Arles, and with Lucien Pissarro; both men would attend Van Gogh’s funeral in Auvers. Of the older Pissarro, Van Gogh would frequently ask Theo to pass on any painterly advice he gave; and he entertained the idea of lodging with Camille, for the sake of Camille’s finances, and towards his own improvement as an artist. In addition to Signac, in Paris Van Gogh worked closely with Toulouse-Lautrec. Toulouse-Lautrec’s use of the peinture à l’essence technique, where oil paint first rests on paper for several hours so that some of its oil is absorbed, and is then thinned with turpentine before being applied to canvas – a technique which Toulouse-Lautrec himself derived from Degas – was borrowed and experimented with by Van Gogh for some of his paintings of Paris and Montmartre.

From the very first, Van Gogh had moved to Arles not only for its light and vibrant colours, but also with the conception of forming an artist’s colony – or at least a retreat which his fellow artists could visit, and from which there would derive inspiration, and the intermingling of diverse ideas. The Yellow House was to be the centre of this vision, and Van Gogh encouraged Gauguin to come and stay there and decorated the house for his arrival. Even after Gauguin left Arles after only two months, at the end of December 1888, still he and Vincent remained in contact, and would resume friendly terms. On 20 March, 1890 – whilst Van Gogh suffered through a sudden, prolonged illness – Gauguin sent him a letter commenting on the recent display of ten of Van Gogh’s paintings at the Artistes Indépendants exhibition in Paris:

It’s above all at this latter place that one can properly judge what you do, either because of things positioned beside each other, or because of the neighbouring works. I offer you my sincere compliments, and for many artists you are the most remarkable in the exhibition. With things from nature you’re the only one there who thinks.

At the Les XX exhibition in Brussels a couple of months earlier, the Belgian Symbolist painter Henry de Groux had taken exception to being exhibited alongside Van Gogh, and had insulted those of Van Gogh’s works on show. In his absence, Van Gogh was defended by Toulouse-Lautrec and Signac, who both challenged De Groux to a duel. De Groux was expelled from Les XX.

Van Gogh’s blossoming orchard triptych hangs today in the Van Gogh Museum, the three paintings shown in white frames alongside a work by the Danish artist Christian Mourier-Petersen. Mourier-Petersen was another painter who Vincent readily befriended and worked alongside. From a wealthy Danish family, he had been a student of medicine before turning to art, which he studied in Copenhagen in 1880. Having undertaken a proposed three-year Grand Tour of Europe, he spent from around 10 October, 1887 until 22 May, 1888 in Arles; before moving on to Paris, where he lodged with Theo from 6 June to 15 August. Van Gogh wrote warmly of Mourier-Petersen and regarded his intelligence, but thought little of his paintings. Mourier-Petersen – who admitted finding Van Gogh a little mad at first – would send Vincent a friendly letter in January 1889, having returned to Denmark upon the conclusion of his travels.

Mourier-Petersen painted with Van Gogh in Arles during the months of March and April. His Blossoming Peach Tree views precisely the same scene as Van Gogh’s The Pink Peach Tree. Perhaps seated slightly to the right of Van Gogh when he painted the scene, Mourier-Petersen’s work features three trees: aside from the one upon which Van Gogh’s composition centres, there appears a tree just behind and to the right in even fuller blossom, and a small shrub positioned in the foreground which serves to frame the work. The shrub’s flowers are white; but Mourier-Petersen’s flowers for the other two trees have remained a vivid pink.

Where the impasto of Van Gogh’s flowers makes their blossoming palpable, felt as vigorous explosions of the spring, Mourier-Peterson’s paint is thinner and his style gentler, with his trees elongated, stretching upwards in their frailty in contrast to Van Gogh’s relatively squat and sturdy depictions. A golden-yellow hue stretches across the extent of the fence in the middle of Mourier-Peterson’s canvas; his fence lilts forwards; the ground comes in tones of pink-orange with silver-blue highlights; and the sky distends in heavy purple-blue.

________

The full text of Van Gogh’s first sermon, Sunday, 29 October, 1876: http://www.vggallery.com/misc/sermon.htm

![Pierrot and Harlequin [Mardi-Gras] (1888-1890) - Paul Cezanne - Gallery of European and American Art - Moscow Musts](https://culturedallroundman.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/03/cezanne-pierrot-and-harlequin.jpg?w=467&h=580)