Archives For November 30, 1999 @ 12:00 am

And so here lies a second painting, in ink and watercolour, of the view from the rear balcony of my old apartment in the Oud-Zuid neighbourhood of Amsterdam.

While the first looked down from the balcony toward two sheds, showing their roofs and yards in autumn with the patternation of fallen leaves, this watercolour shows a perspective across the complex of apartments. I always appreciated the view sitting out on this balcony because – while enclosed – the distance and design was sufficient so that you could be aware of the presence of bodies on other balconies, but rarely noticed anything egregious in their expressions or behaviours. In short, you were well secluded – and the situation reminded me a little of Rear Window, though to the cinema’s potential loss, I never suffered while living there a broken leg.

At the end of last October, my partner and I departed Amsterdam and returned to York. The cause was my commencing a PhD in literature at the University of York. While there were possibilities for undertaking doctoral research at a university which would have enabled us to continue living in Amsterdam – including an excellent opportunity with the University of Antwerp – we ultimately decided that York presented the best scenario for study. Preparations for the move occupied much of late October; there was the fact of the move itself; and then followed the process of finding and inhabiting an apartment in York while also developing a working habit at the University.

That serves as a loose explanation for my lack of posts between last September and mid-March; but as much as I was preoccupied with other things, I simply fell out of the habit of posting. More, during September and October, I began and wrote significant portions and passages for articles which were intended for the site, but never finished. Aside from no longer possessing a surfeit of time, and aside from the diminishing of a regular article-writing habit, the existence of these unfinished pieces served to further pervert the end of publication. As those articles which I had begun became less and less relevant, the inclination was to consider how their material could be repurposed – rather than focusing on what else I ought to write. What had been written became a barrier to further work. The situation in Ukraine and Crimea compelled several pieces last month, and marked my return to posting.

In the last few weeks before we left Amsterdam, I painted a small number of paintings comprising views from the rear balcony of our apartment, in the ‘Oud-Zuid’ of the city. The paintings are in watercolour and ink. Some of their views will be visible in earlier collections of photographs posted on this site; or else via my Instagram account. This first painting looks down upon two sheds, and contains all of the relevant fallen leaves and foliage.

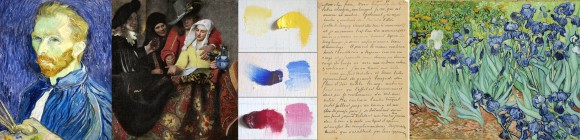

In early April, I began a series on the art of Vincent van Gogh. Propelled by a thematic display of his works at the Hermitage Amsterdam, my series continued on as these works were removed and transported back across the city for the reopening of the Van Gogh Museum, on 1 May, and with a new exhibition, entitled Van Gogh at Work.

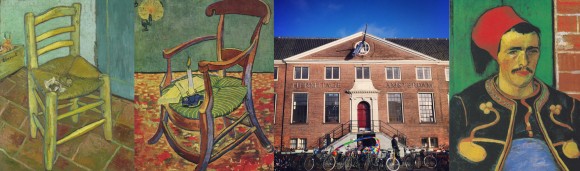

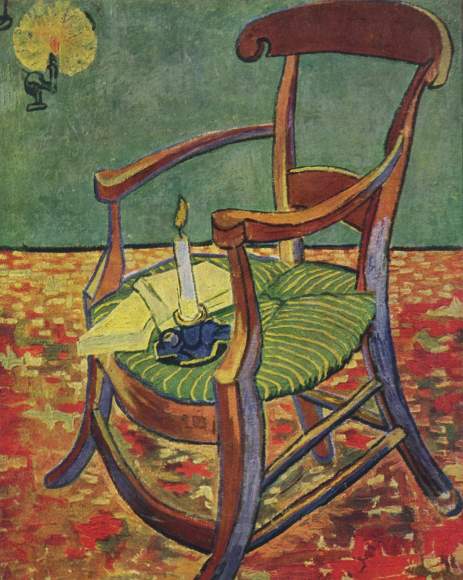

The first piece in my series centred on psychological interpretations of the use of red and green in a number of Van Gogh’s paintings: Gauguin’s Chair, La Berceuse, and The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital. The second piece provided an overview of Van Gogh’s early artistic career, through Brussels, Etten, The Hague, and Nuenen, before viewing the emboldening of his art during the time he spent in Antwerp and Paris. The third piece considered new research undertaken by the Van Gogh Museum into Van Gogh’s artistic practices and use of pigments; and compared his Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background with Vermeer’s The Milkmaid. So in turn these three short essays saw Van Gogh in Arles from late 1888 to the spring of 1889, prior to his installation in the asylum at Saint-Rémy; in Antwerp from late 1885 to early 1886, then in Paris over the next two years; and towards the very close of his year in Saint-Rémy, just as he was about to move on to Auvers-sur-Oise.

It is rare that any endeavour is completed – so many of our tasks are cyclical, looping, or intermittently repeating; and work started upon tends to encourage more ideas, to bring about new prospects, to demand ever-more work. This piece in my series draws from the research and the concerns of the others, and views Van Gogh during his early days in Arles, in the spring of 1888. Van Gogh left Paris for Arles in February. Just as he moved from Antwerp to Paris struggling with ill health – the effects of an insufficient diet, and excessive drinking and smoking – so the move further south was made with Van Gogh ill and seeking a kinder climate. More, he had become exhausted with life in Paris, and sought for his art to be reinvigorated by Arles’ light and its exotic atmosphere.

Though he had become close with Paul Signac living in Paris, and had experimented with pointillism, Van Gogh met Georges Seurat for the first time only in the hours before his departure from the city. Vincent arrived in Arles on 20 February. He found the town under a cover of snow; and began staying in accommodation at the Restaurant Carrel. Immediately setting about his work, between the beginning of March and the end of April he completed fifteen paintings of trees and orchards in blossom. These were prefaced by two still life studies, ‘Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass’ and ‘Blossoming Almond Branch in a Glass with a Book’: the movement between indoors and outdoors, between still life paintings and painting en plein air, was always a fluid movement for Van Gogh; and he kept objects and themes in mind, dwelling on them in sustained short bursts, often returning to them in the longer term.

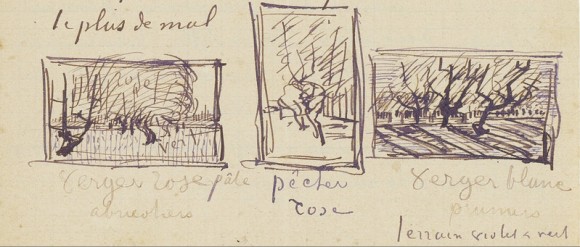

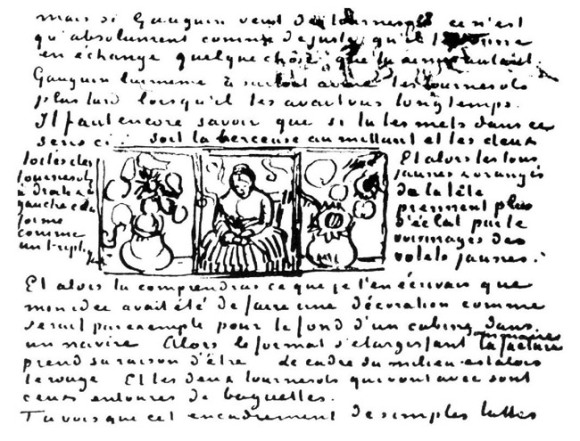

Of the fifteen blossoming orchard scenes he completed, three stand out because, in a letter to Theo on or around 13 April, Vincent explicitly tied them together as a triptych. These are The Pink Orchard (also known as Orchard with Blossoming Apricot Trees), The Pink Peach Tree (or Peach Tree in Blossom), and The White Orchard. Vincent included in his letter a sketch of this triptych. He was increasingly fond of linking his works in such a way, and would later envision his Sunflowers in triptychs, one either side of a La Berceuse. While stating his desire to paint repetitions of his blossom paintings, and his hope to complete at least nine canvases in total – with the implication that these nine canvases would divide into three triptychs – we have no information regarding which of the other finished paintings Vincent may have intended to go together.

In fact, even Vincent’s ink-sketch is not decisive: The Pink Peach Tree is almost identical in composition with The Pink Peach Tree (Souvenir de Mauve), which was the second painting in the blossom series, completed just after The Pink Orchard (The Pink Orchard and Souvenir de Mauve were the first two paintings in the series, from March; whereas The Pink Peach Tree and The White Orchard were the last two, finalised towards the end of April). We can conclude that The Pink Peach Tree is the painting Van Gogh conceived for the triptych because, in a letter to his sister Willemien on 30 March, he expressed his intention to send the earlier painting to the widow of Anton Mauve. Mauve was Vincent’s cousin-in-law and had been an important figure in Van Gogh’s early artistic development; Vincent sent Souvenir de Mauve to Theo in May, and it was subsequently passed on to Mauve’s widow Jet.

Together, the three paintings of the triptych show Van Gogh developing upon the techniques and inspirations of his time in Paris. There is the bold use of vivid colour; and the influence of ukiyo-e Japanese prints evident in his cropped, asymmetrical compositions and his rhythmic lines and contours. In fact, Japonaiserie: Flowering Plum Tree (after Hiroshige), from the autumn of 1887, is a distinct precursor to the series.

Just as in some of his later paintings – including The Bedroom, painted in Arles in October 1888, and Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, painted in May 1890 in Saint-Rémy – the canvases here too demonstrate the diminishing of red pigment over time, for the pink blossom which was present in the first two paintings of the triptych, as indicated by their titles, has faded and become predominantly white.

In The Bedroom and Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, Van Gogh would mix red pigment with blue to arrive at violet-purple. Contrasting this purple with a range of yellows, Van Gogh was thereby remaining true to traditional colour theory, which he had studied in Antwerp. As the red pigment which he utilised has faded, the palette of these two paintings has changed from yellow-purple to yellow-blue; two colours which, while not strictly opposing on the colour-wheel, remain highly complementary. The disappearance of so much pink in Van Gogh’s blossom paintings perhaps represents, therefore, a greater change to the nature of these works and the way they are viewed and considered. With the red pigment’s absence leaving only the white behind, these works take on a luminous, spiritual quality.

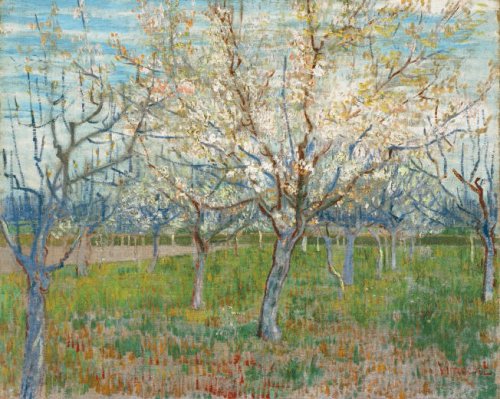

The Pink Orchard well demonstrates the range of painterly techniques which Van Gogh had by this point developed. It features short brushstrokes of red and green for the grass in the foreground, painted thinly and with the canvas showing through – characteristics of some of his paintings of Parisian streets and gardens in Montmartre. Its trees rise in tones of ultramarine, with blue contour lines and bare branches. The composition moves diagonally, from the near left to the far right; this was the first blossom painting Van Gogh painted, early in the season after a long winter, and many of the trees are not in bloom; the handful of trees in the centre which are blooming show flowers painted in impasto, now predominantly white, but with highlights of pink and orange. Set against the contours of the trees and a light-blue, almost turquoise sky, which moves horizontally behind the branches, the painting divides loosely into two colour contrasts: the red/green of the ground, and the blue/oranges of the sky above.

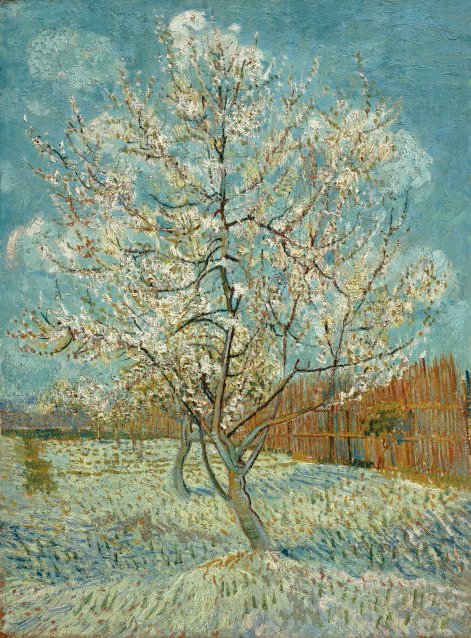

The Pink Peach Tree shows an impasto application of paint throughout, with flowers painted so thickly that they all but hang from the canvas. The central colours here are in the white of the ground and the blossom, in their green highlights, and in the thick blue-turquoise sky painted and suspended around the blossom flowers. The fence to the right of the composition is painted in long verticals and with a diversity of colours again reminiscent of Van Gogh’s 1887 Montmartre paintings; its oranges, browns and reds offset the central, titular, sky-bearing tree, and juxtapose with the lower greens and upper blues.

The White Orchard is the most evenly painted of the three works, and appropriately the one with the least pink in the blossom of its trees. Their white and green blossom, resting upon blue branches, is counterbalanced by the pinks and purples – in fact, mauves – which highlight the ground. This orchard appears in full blossom, the branches of its trees entangling against a delicate sky.

The popular conception of Van Gogh often seems one of a headstrong, difficult and solitary artist; whose relationships with the opposite sex were ill-conceived and ultimately short-lived; who concluded perhaps the most famous co-habitation in the history of art by cutting off his own ear; who went unrecognised in his lifetime; and who died alone in Auvers-sur-Oise. The difficulties he had within specific relationships cannot be denied, and that there was a strong solitary strain to his personality is also clear. In October 1876, years before he embarked upon his artistic career, in a Methodist church in Richmond, England, Van Gogh delivered his first sermon, and opened with the belief ‘I am a stranger on the earth’. Yet this sense of Van Gogh alone does not account for the complexities of his personality, or for the connections he sought and the very real connections he made.

In Paris, Van Gogh became acquainted with Émile Bernard, with whom he began corresponding, especially during his time in Arles, and with Lucien Pissarro; both men would attend Van Gogh’s funeral in Auvers. Of the older Pissarro, Van Gogh would frequently ask Theo to pass on any painterly advice he gave; and he entertained the idea of lodging with Camille, for the sake of Camille’s finances, and towards his own improvement as an artist. In addition to Signac, in Paris Van Gogh worked closely with Toulouse-Lautrec. Toulouse-Lautrec’s use of the peinture à l’essence technique, where oil paint first rests on paper for several hours so that some of its oil is absorbed, and is then thinned with turpentine before being applied to canvas – a technique which Toulouse-Lautrec himself derived from Degas – was borrowed and experimented with by Van Gogh for some of his paintings of Paris and Montmartre.

From the very first, Van Gogh had moved to Arles not only for its light and vibrant colours, but also with the conception of forming an artist’s colony – or at least a retreat which his fellow artists could visit, and from which there would derive inspiration, and the intermingling of diverse ideas. The Yellow House was to be the centre of this vision, and Van Gogh encouraged Gauguin to come and stay there and decorated the house for his arrival. Even after Gauguin left Arles after only two months, at the end of December 1888, still he and Vincent remained in contact, and would resume friendly terms. On 20 March, 1890 – whilst Van Gogh suffered through a sudden, prolonged illness – Gauguin sent him a letter commenting on the recent display of ten of Van Gogh’s paintings at the Artistes Indépendants exhibition in Paris:

It’s above all at this latter place that one can properly judge what you do, either because of things positioned beside each other, or because of the neighbouring works. I offer you my sincere compliments, and for many artists you are the most remarkable in the exhibition. With things from nature you’re the only one there who thinks.

At the Les XX exhibition in Brussels a couple of months earlier, the Belgian Symbolist painter Henry de Groux had taken exception to being exhibited alongside Van Gogh, and had insulted those of Van Gogh’s works on show. In his absence, Van Gogh was defended by Toulouse-Lautrec and Signac, who both challenged De Groux to a duel. De Groux was expelled from Les XX.

Van Gogh’s blossoming orchard triptych hangs today in the Van Gogh Museum, the three paintings shown in white frames alongside a work by the Danish artist Christian Mourier-Petersen. Mourier-Petersen was another painter who Vincent readily befriended and worked alongside. From a wealthy Danish family, he had been a student of medicine before turning to art, which he studied in Copenhagen in 1880. Having undertaken a proposed three-year Grand Tour of Europe, he spent from around 10 October, 1887 until 22 May, 1888 in Arles; before moving on to Paris, where he lodged with Theo from 6 June to 15 August. Van Gogh wrote warmly of Mourier-Petersen and regarded his intelligence, but thought little of his paintings. Mourier-Petersen – who admitted finding Van Gogh a little mad at first – would send Vincent a friendly letter in January 1889, having returned to Denmark upon the conclusion of his travels.

Mourier-Petersen painted with Van Gogh in Arles during the months of March and April. His Blossoming Peach Tree views precisely the same scene as Van Gogh’s The Pink Peach Tree. Perhaps seated slightly to the right of Van Gogh when he painted the scene, Mourier-Petersen’s work features three trees: aside from the one upon which Van Gogh’s composition centres, there appears a tree just behind and to the right in even fuller blossom, and a small shrub positioned in the foreground which serves to frame the work. The shrub’s flowers are white; but Mourier-Petersen’s flowers for the other two trees have remained a vivid pink.

Where the impasto of Van Gogh’s flowers makes their blossoming palpable, felt as vigorous explosions of the spring, Mourier-Peterson’s paint is thinner and his style gentler, with his trees elongated, stretching upwards in their frailty in contrast to Van Gogh’s relatively squat and sturdy depictions. A golden-yellow hue stretches across the extent of the fence in the middle of Mourier-Peterson’s canvas; his fence lilts forwards; the ground comes in tones of pink-orange with silver-blue highlights; and the sky distends in heavy purple-blue.

________

The full text of Van Gogh’s first sermon, Sunday, 29 October, 1876: http://www.vggallery.com/misc/sermon.htm

Here are a selection of documents and sources – videos, images, and text – relating to and referred to in the piece I just published, on the influence of Nicholas Roerich and Asiatic culture on Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

____

Mikhail Glinka, Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842) – Overture

____

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, Op. 35 (1888)

____

Vladimir Soloviev, ‘Pan Mongolism’ (1894)

–

Pan Mongolism! The name is monstrous

Yet it caresses my ear

As if filled with the portent

Of a grand divine fate.

–

While in corrupt Byzantium

The altar of God lay cooling

And holy men, princes, people and king

Renounced the Messiah –

–

Then He invoked from the East

An unknown and alien people,

And beneath the heavy hand of fate

The second Rome bowed down in the dust.

–

We have no desire to learn

From fallen Byzantium’s fate,

And Russia’s flatterers insist:

It is you, you are the third Rome.

–

Let it be so! God has not yet

Emptied his wrathful hand.

A swarm of waking tribes

Prepares for new attacks.

–

From the Altai to Malaysian shores

The leaders of Eastern isles

Have gathered a host of regiments

By China’s defeated walls.

–

Countless as locusts

And as ravenous,

Shielded by an unearthly power

The tribes move north.

–

O Rus’! Forget your former glory:

The two-headed eagle is ravaged,

And your tattered banners passed

Like toys among yellow children.

–

He who neglects love’s legacy,

Will be overcome by trembling fear…

And the third Rome will fall to dust,

Nor will there ever be a fourth.

____

Golden bull figurine, from the Maikop kurgan (excavated 1897)

____

World of Art magazine, 3rd Edition (1901)

____

Nicholas Roerich, Guests from Overseas (1901)

____

Nicholas Roerich, Set Design for Act III of The Polovtsian Dances (1909)

____

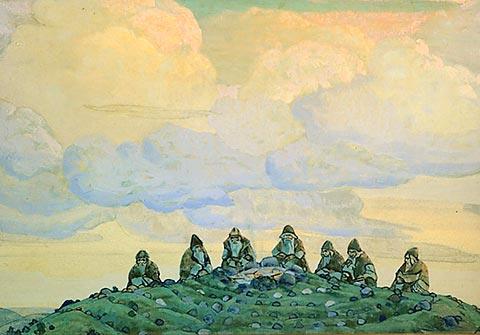

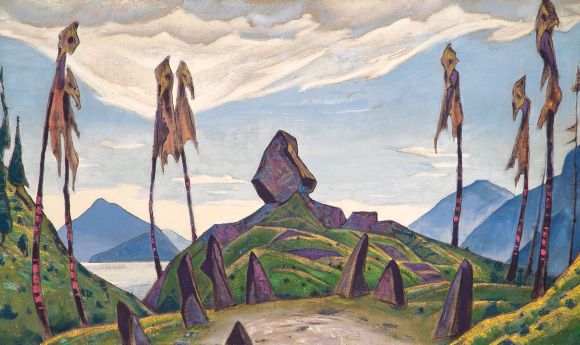

Nicholas Roerich, Preliminary Paintings for ‘The Great Sacrifice’ (the working title of The Rite of Spring) (1910)

____

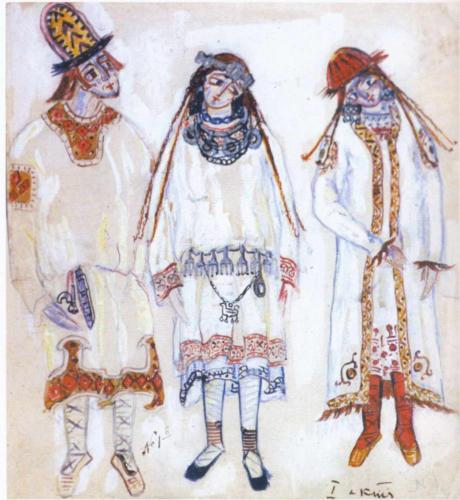

Nicholas Roerich, Costume Designs for The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

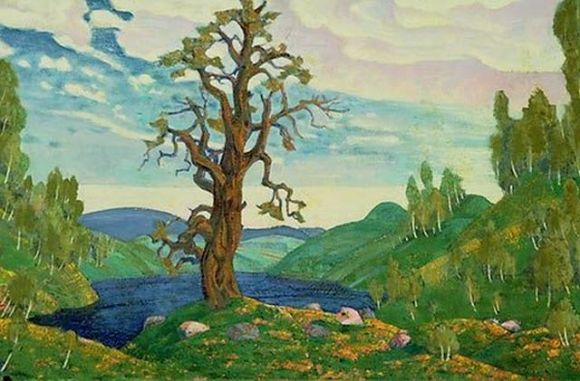

Nicholas Roerich, Set Designs for The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Original Costumes for The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Alexander Blok, The Scythians (1918)

–

You are millions. We are hordes and hordes and hordes.

Try and take us on!

Yes, we are Scythians! Yes, we are Asians –

With slanted and greedy eyes!

–

For you, the ages, for us a single hour.

We, like obedient slaves,

Held up a shield between two enemy races –

The Tatars and Europe!

–

For ages and ages your old furnace raged

And drowned out the roar of avalanches,

And Lisbon and Messina’s fall

To you was but a monstrous fairy tale!

–

For hundreds of years you gazed at the East,

Storing up and melting down our jewels,

And, jeering, you merely counted the days

Until your cannons you could point at us!

–

The time is come. Trouble beats its wings –

And every day our grudges grow,

And the day will come when every trace

Of your Paestums may vanish!

–

O, old world! While you still survive,

While you still suffer your sweet torture,

Come to a halt, sage as Oedipus,

Before the ancient riddle of the Sphinx!..

–

Russia is a Sphinx. Rejoicing, grieving,

And drenched in black blood,

It gazes, gazes, gazes at you,

With hatred and with love!..

–

It has been ages since you’ve loved

As our blood still loves!

You have forgotten that there is a love

That can destroy and burn!

–

We love all- the heat of cold numbers,

The gift of divine visions,

We understand all- sharp Gallic sense

And gloomy Teutonic genius…

–

We remember all- the hell of Parisian streets,

And Venetian chills,

The distant aroma of lemon groves

And the smoky towers of Cologne…

–

We love the flesh – its flavor and its color,

And the stifling, mortal scent of flesh…

Is it our fault if your skeleton cracks

In our heavy, tender paws?

–

When pulling back on the reins

Of playful, high-spirited horses,

It is our custom to break their heavy backs

And tame the stubborn slave girls…

–

Come to us! Leave the horrors of war,

And come to our peaceful embrace!

Before it’s too late – sheathe your old sword,

Comrades! We shall be brothers!

–

But if not – we have nothing to lose,

And we are not above treachery!

For ages and ages you will be cursed

By your sickly, belated offspring!

–

Throughout the woods and thickets

In front of pretty Europe

We will spread out! We’ll turn to you

With our Asian muzzles.

–

Come everyone, come to the Urals!

We’re clearing a battlefield there

Between steel machines breathing integrals

And the wild Tatar Horde!

–

But we are no longer your shield,

Henceforth we’ll not do battle!

As mortal battles rages we’ll watch

With our narrow eyes!

–

We will not lift a finger when the cruel Huns

Rummage the pockets of corpses,

Burn cities, drive cattle into churches,

And roast the meat of our white brothers!..

–

Come to your senses for the last time, old world!

Our barbaric lyre is calling you

One final time, to a joyous brotherly feast

To a brotherly feast of labor and of peace!

____

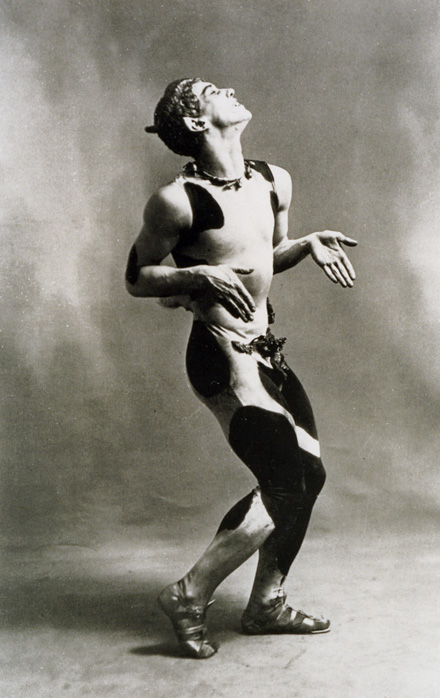

Vaslav Nijinsky

____

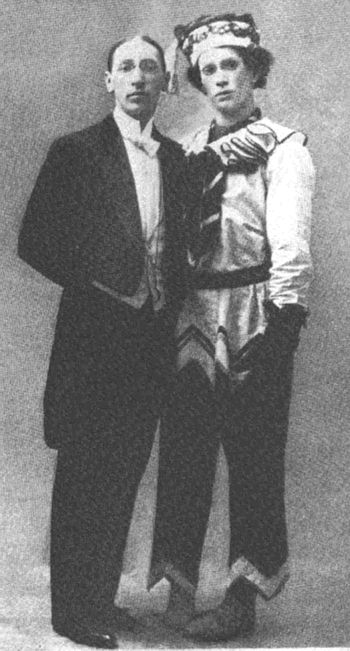

Stravinsky and Nijinsky

____

Credit for the two poems goes to From the Ends to the Beginning: A Bilingual Anthology of Russian Verse; a project hosted at: http://max.mmlc.northwestern.edu/~mdenner/Demo/index.html

The Van Gogh Museum in Amsterdam reopened after seven months a few days ago, 1 May – the culmination of a renovation process which I briefly discussed over at amsterdamarm. The new exhibition which marks the museum’s reopening is entitled Van Gogh at Work, and is the product of eight years of research undertaken by the Van Gogh Museum, the Cultural Heritage Agency of the Netherlands, and researchers from Royal Dutch Shell. This research has brought various confirmations and some new insights regarding Van Gogh’s working practices, his artistic techniques, and his use of materials. We now know, for instance, that during Van Gogh’s two years in Paris, he bought his canvases from the same shop as his colleague Toulouse-Lautrec; and have gained a sense of the frequency with which he recycled canvases, painting over works or utilising both canvas sides.

The research also extends and establishes our understanding of the way in which some of Van Gogh’s pigments have changed and faded through the course of years. The resulting change in the colour of some of Van Gogh’s paintings is the central theme of articles written about the reopening in The New York Times (‘Van Gogh’s True Palette Revealed‘) and The Guardian (‘Van Gogh’s true colours were originally even brighter‘).

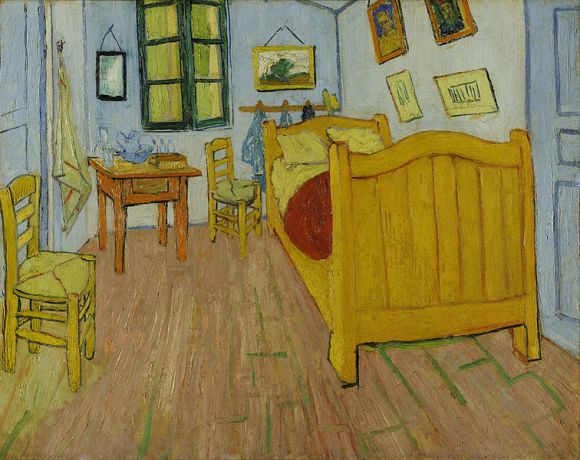

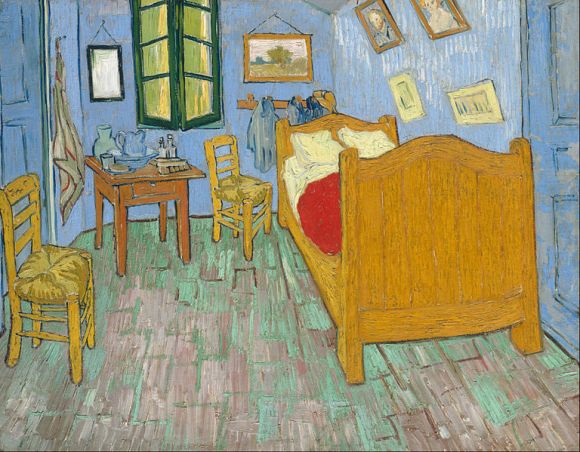

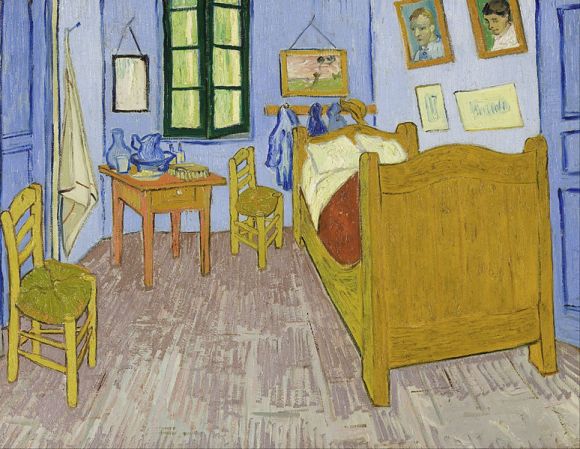

The New York Times piece discusses in particular Van Gogh’s The Bedroom (or Bedroom in Arles). The title refers to three oil paintings: the first painted in Arles in October 1888; the subsequent two painted after the original, in September 1889, whilst Van Gogh was a patient at the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, in Saint-Rémy. The New York Times focuses on the initial painting, held by the Van Gogh Museum; and explains that, whilst its ‘honey-yellow bed pressed into the corner of a cozy sky-blue room’ is so familiar to us today, in fact Van Gogh originally painted the walls of the room in violet. The red pigment which he used to mix this violet has faded over time, leaving only the blue. Marije Vellekoop, the Van Gogh Museum’s head of collections, research and presentation, comments, ‘For me, the purple walls in the bedroom make it a softer image. It confirms that he was sticking to the traditional colour theory, using purple and yellow, and not blue and yellow’.

This diminishing of pigment is less evident in the two Saint-Rémy paintings. The second version of The Bedroom, in the collection of the Art Institute of Chicago, shows more intense, cornflower-blue walls. This version is on loan from Chicago for the duration of the Van Gogh Museum’s exhibition, displayed side-by-side with the Arles rendition. The third version of the painting, held by the Musée d’Orsay, bears more trace of the original violet, the colour of its walls approaching lavender.

The emphasis in the New York Times on these particular colour combinations – on violet and yellow becoming blue and yellow – relates to my series on Van Gogh, inspired by the previous collection of his works at the Hermitage Amsterdam. The first piece in that series, published early last month, is titled ‘Gauguin’s Chair and La Berceuse: Conceptualising Red and Green in the Art of Van Gogh‘. The second piece, published at the start of this week, discusses ‘Van Gogh in Paris: The Radicalising of a Palette and a Brush‘. In it, I depict the months he spent in Antwerp, between late 1885 and early 1886, as crucial to Van Gogh’s artistic development. It was in Antwerp that he studied colour theory and began to broaden his palette; inspired as he was upon arriving in the city by the busy, varied life of its docks, and by the Japanese woodcuts he found on sale there.

This, the third piece in my series, considers precisely the occurrence of a violet and yellow contrast becoming a contrast of yellow and blue. Namely, I want to view Van Gogh’s Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, and compare it with Johannes Vermeer’s The Milkmaid.

Still Life: Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background was one of the last paintings Van Gogh worked on in Saint-Rémy. He completed it in May 1890, before leaving the hospital and moving to Auvers-sur-Oise; where – after achieving dozens more canvases, including his innovative double-square paintings – he would die at the end of July. In marked contrast with the rest of his artistic career, Van Gogh painted relatively few still lifes during his time at Saint-Rémy, painting instead outdoors, in the hospital’s gardens and then in the surrounding countryside. Though he frequently appreciated the order imposed by life at the hospital, and painted prolifically, he continued to experience periods of deep anguish and physical illness.

After suffering what the director of the asylum described as an ‘attack’ on 22 February, Van Gogh kept painting, but wrote few letters over the next two months (he received letters meanwhile from Theo and Gauguin among others; his paintings had recently been shown at Les XX’s annual exhibition in Brussels, and with the Artistes Indépendants in Paris, to the warm acclaim of his fellow artists). This attack motivated his decision, made in early May, to leave for Auvers. Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background was therefore presumably undertaken with his move already firmly in mind. In a couple of letters, Van Gogh writes of working in a ‘frenzy’ during his last few days in Saint-Rémy.

He had completed two studies of irises, out in the garden of Saint-Paul, the previous May, soon after committing himself to the asylum following his time in Arles. Theo greatly admired these, and submitted them to the Société des Artistes Indépendants’ annual exhibition in September. Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background was one of two still lifes with irises which Van Gogh painted a year after these studies. In his own words, in a letter to Theo,

At the moment the improvement is continuing, the whole horrible crisis has disappeared like a thunderstorm, and I’m working here with calm, unremitting ardour to give a last stroke of the brush. I’m working on a canvas of roses on bright green background and two canvases of large bouquets of violet Irises, one lot against a pink background in which the effect is harmonious and soft through the combination of greens, pinks, violets. On the contrary, the other violet bouquet (ranging up to pure carmine and Prussian blue) standing out against a striking lemon yellow background with other yellow tones in the vase and the base on which it rests is an effect of terribly disparate complementaries that reinforce each other by their opposition.

The crisp contours of the leaves and the Japanese-influenced diagonals of the flowers are set against a background which moves thickly around them. Indeed, Van Gogh painted this background last, after the flowers and vase. Yet in the painting as it appears today, the carmine – that pure, rich red which Van Gogh mentions as a facet of it – only faintly remains. As with The Bedroom‘s walls, the violet flowers have turned blue. In this manner, Van Gogh’s art makes explicit the idea that all art is involved in a continual process of becoming. In the particular case of Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background, Van Gogh’s painting has become a perfect Vermeer: echoing in its current form Vermeer’s predisposition for the bold and brilliant use of yellow and blue.

Vermeer’s The Milkmaid evinces both this predisposition for colour and his strikingly modern painterly techniques. It was painted around 1668, when Vermeer was just twenty-five years old. In some respects Vermeer is a difficult artist to analyse, for only 34 paintings remain attributed to him, and there is a dearth of material and information relating to his studies and preparatory methods. He appears about 1665 already remarkably accomplished and mature. Broadly, there is something readier, a little rougher, more captured than composed about his earlier works.

Yellow and blue are the dominant colours of The Milkmaid. In the organisation of these, Van Gogh’s Vase with Irises Against a Yellow Background appears like The Milkmaid reversed. The distinguishing feature of Vermeer’s palette, when contrasted with those of his contemporaries, was his use of expensive natural ultramarine: this gives his blues here an exceptional vividness, in tune with his similarly luminous handling of lead-tin yellow. Yet the colour combinations in The Milkmaid are complex and various, and not limited to yellow and blue. The contrast in these colours is repeated in the rich contrast between the green of the tablecloth and the maid’s carmine-red skirt.

The same green depicts the milkmaid’s rolled oversleeves, which Vermeer painted alla prima (wet-on-wet), mixing and working the yellow and blue of the maid’s shirt and apron. This method was not uncommon amongst Early and Golden Age Dutch painters: it was adopted by Jan van Eyck and by Rembrandt for several of their compositions. It became a characteristic of many Impressionist and Post-Impressionist paintings, aided by the new availability of pigments in portable tubes, which allowed artists like Van Gogh to go out into nature and paint rapidly en plein air.

A further aspect which links Vermeer to the art of the Impressionists is his use of a pointillé technique – patterns of small dots which, to a modern eye, evoke the pointillism of Seurat and Signac, with which Van Gogh experimented. Collections of small, white dots add texture and suggest the play of light in Vermeer’s painting, noticeable especially on the bread and on the top of the maid’s apron; highlighting also her cap, oversleeves, and the lip of the jug with which she pours. They enhance the atmosphere of softly diffusing light which characterises this brilliant but gentle, boldly restrained, most harmonious of works.

A few weekends ago, I began what is intended as a short series, impelled by the selection of paintings by Vincent van Gogh which have been on show at the Hermitage Amsterdam. The exhibition there, entitled Vincent, comprised a thematic arrangement of seventy-five paintings whilst the Van Gogh Museum was undergoing refurbishment. It came to a close – having run since September – at the end of last week; with the Van Gogh Museum to reopen this Wednesday, 1 May.

The purpose of my series is to consider and draw out some of the aspects and juxtapositions which the thematic display at the Hermitage Amsterdam suggested. I gave the first piece in my series the title ‘Gauguin’s Chair and La Berceuse: Conceptualising Red and Green in the Art of Van Gogh’. This is the second of the series; a third part will be published here over the next week.

Having essentially foregone an early career as an art dealer; then failing on his explicitly religious mission; Van Gogh turned to art around 1880, at the age of twenty-seven. He had drawn frequently while pursuing a religious ministry in the Borinage through 1879; dismissed from his post there by the authorities – due to his unkempt appearance and squalid living conditions, which rendered him indistinguishable from the miners and peasants he was supposed to be ministering to – Van Gogh embarked in earnest on an artistic pathway; and in 1880 was encouraged to travel to Brussels, where he enrolled, in November, at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts, to study drawing formally.

He was in Brussels only a few months before moving with his parents to Etten, where he resumed drawing the countryside and the locals. After a string of arguments with his family concerning his lifestyle, his prospects, and his forceful and hasty attempts to begin a relationship with his widowed cousin, Kee Vos-Stricker, Van Gogh departed from his family in late 1881, and moved to The Hague. It was here that Van Gogh began painting. He was instructed in oil and watercolour by his cousin-in-law, the realist painter Anton Mauve. Though he continued to admire Mauve, and held him as a model artist, the pair soon fell out – owing, Van Gogh believed, to Mauve discovering and disapproving of his nascent relationship with Clasina Maria Hoornik, ‘Sien’, a prostitute who was pregnant when she and Van Gogh first met. Van Gogh lived with Sien, her young daughter, and her infant son, from the middle of 1882 until the autumn of 1883 – when he abruptly left, moving to Drenthe, then soon on to Nuenen.

Van Gogh’s first acclaimed artistic compositions were painted in Nuenen. Commencing at the beginning of 1884, the numerous studies Van Gogh made of weavers, of still lifes, of peasants’ heads, culminated in The Potato Eaters, which he completed in April 1885. There are some consistencies in these early paintings with Van Gogh’s later works: shared compositional characteristics, for instance a perspective when painting buildings whereby the top and front of the building comes towards the viewer, appearing both sturdy and dynamic (compare The Cottage (1885) and Old Cemetery Tower at Nuenen (1885) with The Church at Auvers (1890)); and a thick application of paint. Yet these Nuenen scenes were dark, often dimly lit and with brown the predominant colour; there are none of the vivid colour combinations, bold lines and lively brushstrokes for which Van Gogh is most recognised.

Van Gogh’s art changed in stages and owing to key influences. He left Nuenen for Antwerp in November 1885. Immediately enthralled by Antwerp’s bustling docks, and by the Japanese woodcuts on sale there, he conflated the two in a letter to Theo soon after arriving, on 28 November. In this letter, he evocatively describes the mass of contrasting figures and scenes which have caught his eye on walks about the docks; and tellingly for his art explains:

One of De Goncourt’s sayings was ‘Japonaiserie for ever’. Well, these docks are one huge Japonaiserie, fantastic, singular, strange — at least, one can see them like that.

I’d like to walk with you there to find out whether we look at things the same way.

One could do anything there, townscapes — figures of the most diverse character — the ships as the central subject with water and sky in delicate grey — but above all — Japonaiseries.

I mean, the figures there are always in motion, one sees them in the most peculiar settings, everything fantastic, and interesting contrasts keep appearing of their own accord.

…

The overall effect of the port or of a dock — sometimes it’s more tangled and fantastic than a thorn-hedge, so tangled that one can find no rest for the eye, so that one gets dizzy, is forced by the flickering of colours and lines to look now here and now there, unable to tell one thing from another even after staring at a single spot for a long while.

Whilst in Antwerp, Van Gogh took exams at the city’s Academy of Fine Arts. However, he was drinking heavily and became sick, and in March moved to Paris where he stayed, despite his brothers’ reservations, with Theo. The two years Van Gogh spent in Paris before departing for Arles were full of experimentation; he was able to view the Impressionists and Cézanne, but was propelled most by his fervour for ‘Japonaiseries’, his introduction to the works of Monticelli, and his acquaintance with Paul Signac. His palette became progressively brighter and more colourful, and towards the end of 1886, and through the spring of 1887, his brush came to life.

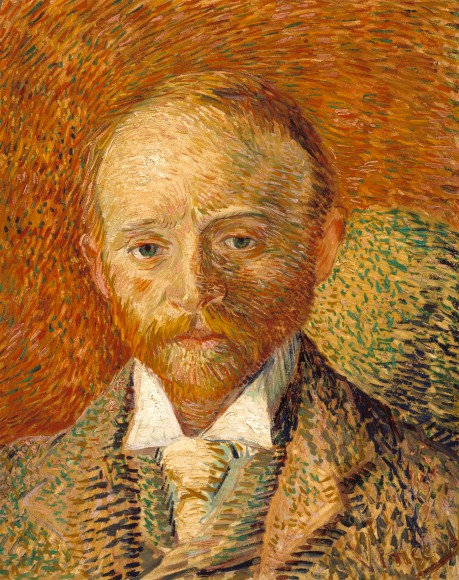

A number of paintings from this period – the endpoints and focal paintings of this piece – demonstrate this conflux of influences. In late 1886 Van Gogh began a group of portraits which evince looser brushstrokes and highlights, resulting in more nuanced and energetic works of art. These include Self-Portrait with Grey Felt Hat; Portrait of a Man with a Skull Cap, the first two of three portraits of Père Tanguy (the first a typical portrait, the second highly colourised with Tanguy seated in front of a Japanese screen and Japanese prints – which Van Gogh reworked a year later for the third piece); and Portrait of the Art Dealer Alexander Reid.

Compared with these portraits, around March 1887, Agostina Segatori Sitting in the Café du Tambourin is less posed, Van Gogh capturing Agostina from a short distance, seemingly lost in thought, with a single Japanese print suggested on the wall behind. All of these paintings are radical extensions – in colour and in brushwork – upon the portraits Van Gogh had painted previously. Some of the street scenes and landscapes which Van Gogh produced in the same spring appear more radical departures than extensions in any linear sense.

Boulevard de Clichy is comprised of short, narrow, but consistent lines, and an almost neon palette with prominent greens and pink-purples. The thin application of paint, with the canvas apparent between brushstrokes, is quite unlike the impasto of Van Gogh’s later career. The colours and the dress and poise of the figures show the effects of the Japanese woodcuts Van Gogh was continuing to collect. View of Paris (or View of Paris from Vincent’s Room in the Rue Lepic) demonstrates a thicker application of paint, and the marked influence of the pointillism practiced by Seurat and Signac; quick lines are joined and overlaid by dots of paint, with juxtapositions of blue and yellow, green and red.

The Stedelijk Museum recently altered those Van Goghs showing from its collection; La Berceuse has left the wall, and in its place has appeared one of a group of paintings Van Gogh made of vegetable gardens in Montmartre. Completed towards that summer, Vegetable Gardens in Montmartre (also known as Kitchen Gardens in Montmartre) shows the same utilisation of thin lines and vibrant colours, here moving rhythmically in all directions to produce a coherent composition. These paintings, as much as Van Gogh’s emerging qualities as a painter, emphasise his skill as a draughtsman; echoing his drawings, predating his revolutionary use of the reed pen in Arles.

The Hermitage Amsterdam’s exhibition Vincent – bringing together seventy-five of the paintings of Vincent van Gogh, plus drawings and letters, whilst the Van Gogh Museum undergoes refurbishment – is into its final few weeks. The exhibition, which began 29 September last year, will run until 25 April; with the works then being relocated to the Museumplein for the reopening of the Van Gogh Museum on 1 May.

Van Gogh’s temporary stay at the Hermitage Amsterdam has allowed his paintings to be shown in a novel way: his works are displayed not chronologically, but according to seven themes – in order, ‘Practice makes perfect’, ‘A style of his own’, ‘The effect of colour’, ‘Peasant painter’, ‘Looking to Japan’, ‘The modern portrait’, and ‘The wealth of nature’ – with a room or section devoted to each theme, and each section’s walls a different colour. The strength of this approach is that it juxtaposes the broad range of techniques by which Van Gogh painted; shows where subject matter and method remained consistent despite a divergence of painterly styles; and highlights illuminating points of connection between paintings which might not otherwise be displayed together. Over the final few weeks of the exhibition, I intend to discuss and compare here a few of the paintings which Vincent has encouraged me to consider and appreciate.

As its heading indicates, the third theme and the third room of the exhibition has as its focus Van Gogh’s use of colour. In particular, it consists of a group of paintings significant for their use of bold colour and bold colour contrasts (the room itself is notable for bearing one of the paintings from Van Gogh’s Arles Sunflowers series). Two of the paintings which have most stood out for me from this room are Gauguin’s Chair and The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital: painted a year apart; featured a few paintings apart in the room; and both predominating in reds and greens.

The caption the museum provides for The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital notes Van Gogh’s psychological interpretation of the colours in the painting. It draws upon a letter Van Gogh sent to his fellow painter Émile Bernard on 26 November, 1889, whilst finishing off work on the canvas. That letter can be read in full here; the two paragraphs in which Van Gogh depicts his painting read:

Here’s description of a canvas that I have in front of me at the moment. A view of the garden of the asylum where I am, on the right a grey terrace, a section of house, some rosebushes that have lost their flowers; on the left, the earth of the garden — red ochre — earth burnt by the sun, covered in fallen pine twigs. This edge of the garden is planted with large pines with red ochre trunks and branches, with green foliage saddened by a mixture of black. These tall trees stand out against an evening sky streaked with violet against a yellow background. High up, the yellow turns to pink, turns to green. A wall — red ochre again — blocks the view, and there’s nothing above it but a violet and yellow ochre hill. Now, the first tree is an enormous trunk, but struck by lightning and sawn off. A side branch thrusts up very high, however, and falls down again in an avalanche of dark green twigs.

This dark giant — like a proud man brought low — contrasts, when seen as the character of a living being, with the pale smile of the last rose on the bush, which is fading in front of him. Under the trees, empty stone benches, dark box. The sky is reflected yellow in a puddle after the rain. A ray of sun — the last glimmer — exalts the dark ochre to orange — small dark figures prowl here and there between the trunks. You’ll understand that this combination of red ochre, of green saddened with grey, of black lines that define the outlines, this gives rise a little to the feeling of anxiety from which some of my companions in misfortune often suffer, and which is called ‘seeing red’. And what’s more, the motif of the great tree struck by lightning, the sickly green and pink smile of the last flower of autumn, confirms this idea.

The notion that the interplay of reds and greens in the painting relate to a ‘feeling of anxiety’ is interesting in its own right, and conducive for comparison; especially since the same combination is to be found in Gauguin’s Chair.

Gauguin’s Chair was completed in December, 1888. Van Gogh had moved to Arles from Paris in February of that year, enticed by the warmer climate – his health was poor; he was suffering from a persistent cough – and having some idea of forming an artists’ colony. Staying at a couple of hotels, he signed a lease for what would become known as the Yellow House, 2 Place Martine, on 1 May; but didn’t move into the house until late September when, furnishing it with two beds, he began to prepare for the arrival of Gauguin, whom he had enthusiastically encouraged to come and stay. Gauguin arrived 23 October; but just a couple of months later tensions between the pair had reached such a point that, so the account goes, on the evening of 23 December, Van Gogh stalked Gauguin through the streets of Arles with a razor, before ultimately cutting off part of his own ear.

Gauguin returned to Paris. Van Gogh spent the next few months in and out of hospital until, on 8 May, 1889, he entrusted himself to the care of the asylum of Saint-Paul-de-Mausole, in Saint-Rémy. Van Gogh was initially confined by his doctor to the asylum’s walled garden; though he gradually began taking trips out into the surrounds, he painted numerous paintings of the garden and of details within it, its trees, tree branches and flowers. The canvas The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital showing at the Hermitage Amsterdam is one of two nearly identical paintings of the Saint-Paul garden, which Van Gogh painted between November and December (within Van Gogh’s catalogue, F numbers 659 and 660).

Van Gogh mentioned Gauguin’s Chair in four letters to his brother Theo (letters 721, 736, 751, and 767, written between November 1888 and May 1889) and in one to the art critic Albert Aurier (letter 853, in February 1890). He calls the ‘twin studies’ – that is, Gauguin’s Chair and Van Gogh’s Chair, the painting of his own chair, with pipe, which he completed in tandem – ‘rather funny’; notes their ‘thick impasto’; and describes the former’s ‘broken tones of red and green’ in the letter to Aurier, in which he writes warmly of Gauguin and states that he owes Gauguin ‘a great deal’. Yet Van Gogh offered no analysis of the work, nor suggested any revealing purpose for it.

It is tempting to view the twin studies as comprising, together, a piece of artistic symbolism – a mode of expression, incidentally, more associated with Gauguin. The empty chairs themselves encourage a symbolical interpretation; and knowing the difficulties in the two painters’ relationship, and the disastrous climax of their time spent living together in Arles, it is easy to see Van Gogh’s Chair – with its soft blues and bright yellows and oranges – representing warmth and openness, the reds and greens of Gauguin’s Chair Van Gogh’s way of suggesting something agitated, even deceptive in his companion. There are other points which could be made – Van Gogh’s chair appears less sturdy, more prone to flight, where Gauguin’s merges with the floor – but Van Gogh’s remarks concerning the palpable anxiety of The Garden of Saint-Paul Hospital support this point-of-view.

Yet at the same time as Van Gogh was working on Gauguin’s Chair, he began a group of paintings of Augustine Roulin which feature a decidedly similar palette and thick application of paint. Augustine Roulin and her husband, Joseph, a postman, became close friends with Van Gogh during his time in Arles, and he painted numerous studies of both husband and wife, as well as their three children. Completing his first painting of Augustine in December 1888, Van Gogh would repeat the same composition four more times: twice in January, and once in February and March. He entitled these paintings La Berceuse, which means ‘The Lullaby’. The March repetition is in the collection of and has been recently showing at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam.

As implied by the title he gave to the paintings, Van Gogh saw La Berceuse evoking a sense of maternal affection and comfort. He considered the painting first in a letter which he sent to Gauguin, on 21 January, after Gauguin’s departure; then expanded on his thoughts to Theo on 28 January:

On the subject of that canvas, I’ve just said to Gauguin that as he and I talked about the Icelandic fishermen and their melancholy isolation, exposed to all the dangers, alone on the sad sea, I’ve just said to Gauguin about it that, following these intimate conversations, the idea came to me to paint such a picture that sailors, at once children and martyrs, seeing it in the cabin of a boat of Icelandic fishermen, would experience a feeling of being rocked, reminding them of their own lullabies. Now it looks, you could say, like a chromolithograph from a penny bazaar. A woman dressed in green with orange hair stands out against a green background with pink flowers. Now these discordant sharps of garish pink, garish orange, garish green, are toned down by flats of reds and greens. I can imagine these canvases precisely between those of the sunflowers – which thus form standard lamps or candelabra at the sides, of the same size; and thus the whole is composed of 7 or 9 canvases.

In a letter to Theo around 23 May, Van Gogh detailed his strengthening conception that the Berceuse paintings should form tritptychs with the Arles Sunflowers series. Van Gogh’s idea was that a La Berceuse should sit in between two Sunflowers; and he wanted both Theo and Gauguin to possess versions. A consideration of the colour combinations this would entail – red and green flanked by orange and yellow – emphasises that Van Gogh may have considered his two chair paintings decidedly complementary, rather than somehow opposed or antagonistic. Exhibitions which feature the paintings routinely display the chairs facing away from one another, thereby running with a symbolic interpretation which is in tune with the popular account of relations between the artists. Van Gogh, of course, painted the Arles Sunflowers to greet Gauguin and to decorate the house he hoped they would contentedly and productively share.

Van Gogh’s contemplating on La Berceuse eschews any simple analysis of Gauguin’s Chair. As viewers we may have recourse to look also towards the rhythms and contours of Van Gogh’s painting; and may wonder at the differences which demarcate and define portraits, studies of objects, and paintings of and in nature. There are other paintings too in Van Gogh’s oeuvre which play on contrasts between red and green: for instance, Paul Gauguin (Man in a Red Beret), which Van Gogh is believed to have painted in early December 1888, with its swirls of green in Gauguin’s jacket, his rich red beret set against the lime-coloured walls, and a peculiar grey brushstroke serving as his nose; and The Zouave, whose red cap is backed by a green door, painted in June 1888.

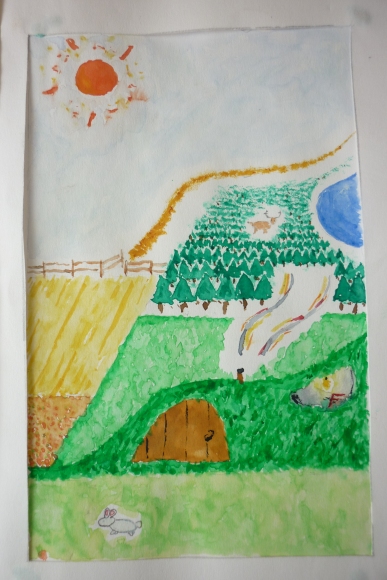

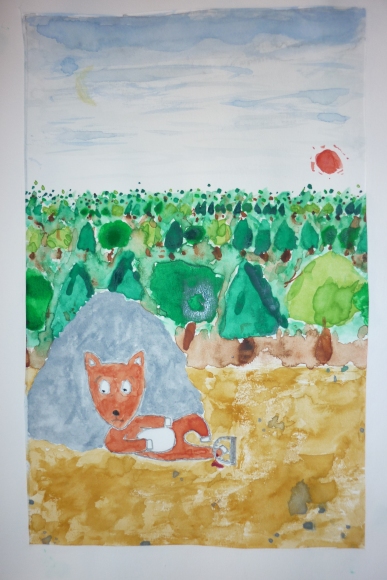

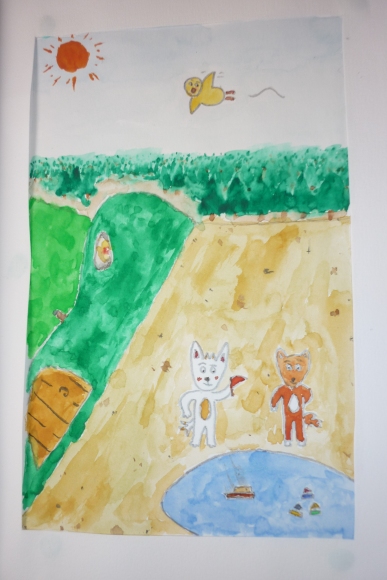

A number of years ago, with my partner and I living in Umeå in the north of Sweden, my partner was afforded the opportunity to study for six months in Istanbul. So we went and we lived in Istanbul for about six months, from the beginning of a September until the latter days of the subsequent February.

My partner was able to study a variety of courses in Istanbul, some only tenuously related to her degree; and one of these courses saw her tasked with writing a children’s story. I provided the illustrations, twelve small watercolour paintings.

I wanted to use the fox for a cutout animation I intend to play around with, so we found the book, or booklet; and I thought I’d post images of the paintings here.

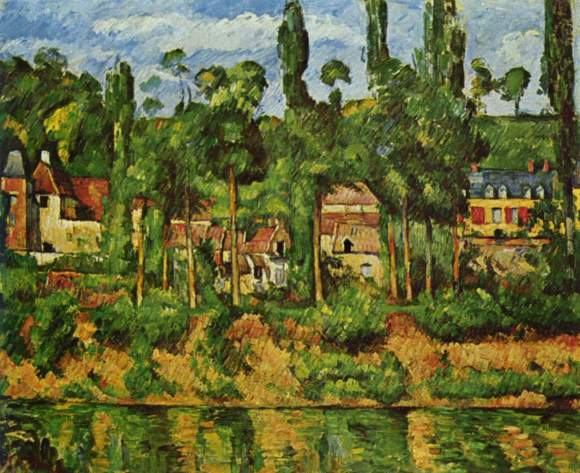

In a piece on Cézanne’s Banks of the Marne, published on this site several weeks ago, I mentioned and briefly considered, by way of comparison, the painting Zola’s House at Médan. The painting is just as often referred to as Le Château de Médan; it was painted between 1879 and 1881; and is now part of the Burrell Collection in Glasgow.

Over the last week I have been reading through a book on Cézanne by Hajo Düchting, published by Taschen, entitled on the front cover simply Cézanne; with the title page expanding upon this via the provision of a subtitle, 1839-1906, Nature into Art. The book makes particular mention of Zola’s House at Médan; and includes a lengthy quotation by Gauguin which I thought was worth republishing here.

Gauguin is recorded as the painting’s first owner, purchasing it from the Parisian art supplier and art dealer Julien François Tanguy. Over the course of years, Tanguy established in his shop quite a collection of Impressionist paintings, owing to the fact that, where money was lacking, he accepted paintings in exchange for paints. He was called Père by his artists, and sold, or attempted to sell, works by Monet, Sisley, Seurat and Van Gogh alongside Cézanne and Gauguin. Van Gogh painted him three times, the latter two paintings increasingly experimental, Japanese-inspired portraits.

Gauguin’s remarks provide us with his own sense of the interplay of colours in Cézanne’s painting. They continue with a second-hand account of an occurrence which took place with Cézanne mid-paint. This account is humorous in its evocation of the professorial passer-by, it provides a nice depiction of Cézanne’s character, and it is also a suggestive shot of a perhaps not atypical contemporary response to Cézanne’s work. Here is Gauguin:

Cézanne is painting a shimmering landscape against an ultramarine background, with intense shades of green and ochre gleaming like silk. The trees are stood in a row like tin soldiers, and through the tangle of branches you can make out his friend Zola’s house. Thanks to the yellow reflections on the whitewashed walls, the vermilion window shutters take on an orange tone. A crisp Veronese green convey the sumptuous leafage in the garden, and the sobre, contrasting shade of bluish nettles in the foreground renders the simple poem even more sonorous.

A presumptuous passer-by takes a shocked glance at what seems, in his eyes, to be a dilettante’s wretched daubing, and asks Cézanne in a professorial voice, with a smile,

‘Trying your hand at painting?’

‘Yes – but I’m no expert!’

‘I can see that. Look here, I was once a pupil of Corot. If you don’t mind, I’ll just add a few well-placed strokes and set the whole thing right. What count are the valeurs, and the valeurs alone.’

And sure enough, the vandal adds a few strokes of paint to the shimmering picture, utterly unabashed. The oriental silk of this symphony of colour is smothered in dirty greys. Cézanne exclaims: ‘Monsieur, you have an enviable talent. No doubt when you plant a portrait you put shiny highlights on the tip of the nose just as you would on the bars of a chair.’

Cézanne picks up his palette once more and scratches off the mess he has made. Silence reigns for a moment. Then Cézanne lets fly a tremendous fart, and, gazing evenly at the man, declares: ‘That’s better.’