Igor Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring (in French, Le Sacre du printemps) – the third ballet which Stravinsky composed for Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes, after The Firebird (1910) and Petrushka (1911) – was written for the 1913 Paris season, and premiered just over a hundred years ago, on 29 May, in the newly-opened Théâtre des Champs-Élysées. The centenary of this most notorious premiere is the occasion for numerous celebrations: new performances, revivals, and festivals which will extend across the next year. The Théâtre des Champs-Élysées is hosting a range of balletic and orchestral performances, in a programme led by Saint Petersburg’s Mariinsky Ballet. In Moscow, four choreographies of the work have been shown by the Bolshoi Ballet over the last two months; with their performance of Pina Bausch’s interpretation set to travel worldwide. The Barbican and the Southbank Centre in London will feature orchestral performances of Stravinsky’s music. Carolina Performing Arts at Chapel Hill have devoted the next year to various showings of the work.

In Amsterdam, as part of the Holland Festival, the Chinese-born choreographer Shen Wei has produced a new version for Het Nationale Ballet. The Paul Sacher Foundation in Basel – which houses the Stravinsky archive – and Boosey & Hawkes are publishing a three-volume centenary edition comprising essays and an annotated facsimile of the score. In Zurich, David Zinman – who studied under and served as assistant to Pierre Monteux, the conductor of The Rite of Spring premiere – will investigate the musical and literary facets of the Rite with the Tonhalle Orchestra on 8 and 9 June. It is something of this endeavour which this piece will also attempt: an exploration of the cultural currents in Russia, centring on conceptions of the East, which led to the development of The Rite of Spring.

The influence of Asiatic art on Russian art, and in the realm of music in particular, was especially evident from the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Mikhail Glinka, the father of Russian classical music, drew extensively in his compositions from Russian folk music, which he had heard growing up as a child near Smolensk, and which was being annotated and collected from the last decade of the 1700s. Glinka’s Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842), an opera in five acts based on Pushkin’s poem, is considered an example of orientalism in music owing to its use of dissonance, chromaticism, and folk melodies. Following Glinka’s lead, Mily Balakirev began combining folk patterns with the received body of European classical music.

Balakirev utilised syncopated rhythms, while Orlando Figes – in Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia – argues that his key innovation was the introduction into Russian music of the pentatonic scale. The pentatonic scale has five notes per octave, in contrast to the heptatonic scale, which has seven and which characterised much of the European music of the common practice era between 1600 and 1900. While the pentatonic scale has been diversely used, it is a prominent aspect of South-East Asian music, and is a facet of many Chinese and Vietnamese folk songs. Figes asserts that Balakirev derived his use of the pentatonic scale from his transcriptions of Caucasian folk songs; and writes that this innovation gave ‘Russian music its ‘Eastern feel’ so distinct from the music of the West. The pentatonic scale would be used in striking fashion by every Russian composer who followed…from Rimsky-Korsakov to Stravinsky’.

Balakirev was the senior member of the group of composers also comprising Modest Mussorgsky, Alexander Borodin, Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, and César Cui – known variously as The Five, The Mighty Handful, and the kuchkists (‘handful’ in Russian being ‘kuchka’, (кучка)). Balakirev’s compositional manner aside, the central philosophical force upon this group was Vladimir Stasov, who as a critic relentlessly forwarded a national school in the Russian arts. Balakirev’s King Lear (1861), Mussorgsky’s Pictures at an Exhibition (1874), and Rimsky-Korsakov’s Sadko (the name for a tone poem of 1867, and for the opera of 1896) and Scheherazade (1888) were all dedicated to Stasov.

From the early 1860s, Stasov researched and wrote a series of analyses demonstrating the influence of the East ‘manifest in all the fields of Russian culture: in language, clothing, customs, buildings, furniture and items of daily use, in ornaments, in melodies and harmonies, and in all our fairy tales’. His extensive study of the byliny, traditional Russian epic narrative poems, led him to conclude ‘these tales are not set in the Russian land at all but in some hot climate of Asia or the East…There is nothing to suggest the Russian way of life – and what we see instead is the arid Asian steppe’.

While positing the influence of the East was one thing, stating that these traditional Russian songs were in fact not Russian, but had originated entirely elsewhere, drew for Stasov considerable criticism. Any picture of the relationship between Russian and Asiatic art is complex: the developing understanding of this relationship in Russia throughout the 1800s is entwined with so many political and artistic movements and events: the emergence of orientalism after Russia’s annexing of the Crimea in 1783, and while they fought the Caucasian War between 1817 and 1864, which gave Russians a new awareness of and access to the south, and which impelled Lermontov’s A Hero of Our Time; the persisting influence of Western Europe, encouraged in literature by the critic Vissarion Belinsky; and the Slavophilism which opposed the predominance of the West, seeking instead the emergence of a truly distinct Russia rooted in its own past. This Slavophilism gained momentum after the Crimean War from 1853-1856, which saw the British and French empires join the Ottomans against Russia. It was inextricably linked with the Orthodox religion; bore the related pochvennichestvo ‘native soil’ movement; and implicated in different ways Nikolai Gogol and Fyodor Dostoevsky.

Such complexities are encapsulated in a piece Dostoevsky wrote for his A Writer’s Dairy – a periodical he wrote and edited, containing polemical essays and occasional short fiction – in 1881. Dostoevsky, an ardent Slavophile for much of the second-half of his life, advocates for the progress of Russia through an engagement with Asia which will, at the same time, renew Russia’s relationship with Europe:

‘It is hard for us to turn away from our window on Europe; but it is a matter of our destiny…When we turn to Asia, with our new view of her, something of the same sort may happen to us as happened to Europe when America was discovered. With our push towards Asia we will have a renewed upsurge of spirit and strength…In Europe we were hangers-on and slaves, while in Asia we shall be the masters. In Europe we were Tatars, while in Asia we can be Europeans.’

All this is the long background to The Rite of Spring. The Symbolists who would achieve a Silver Age of Russian Literature were influenced by a combination of orientalism, folk tales, European literature, their Russian forebears, and some of those philosophers and mystics who were a product of the heightened religious thinking that was so much a part of Slavophilism. The philosopher Vladimir Soloviev – a close friend of Dostoevsky – has been characterised by D. S. Mirsky as ‘the first Russian thinker to divorce mystical and Orthodox Christianity from the doctrines of Slavophilism’, thereby establishing a metaphysics apart from nationalist sentiment. Mirsky depicts Soloviev as leaning towards Rome in matters of theology, and as a Westernising liberal politically. Yet he too was fascinated with the East. An important figure for Andrei Bely – whom Mirsky places alongside Gogol and Soloviev as the three ‘most complex and disconcerting figures in Russian literature’ – and for Alexander Blok, Blok’s The Scythians takes for its epigraph two lines from Soloviev’s 1894 poem ‘Pan-Mongolism’: ‘Pan-Mongolism! What a savage name!/Yet it is music to my ears’.

The Scythians was Blok’s last major poem, completed in 1918, just after The Twelve. Mirsky calls it an eloquent piece of writing, but ‘on an entirely inferior level’ as compared with ‘musical genius’ of The Twelve. Its title references the group of poets of the same name: an offshoot of Russian Symbolism in so far as it consisted of its two leading figures, Bely and Blok, plus the writer Ruzumnik Ivanov-Razumnik.

The Scythians as an ethnographic group were nomadic Iranian-speaking tribes, who inhabited the Eurasian steppes around the Black and Caspian seas from about the eighth century b.c.. Herodotus believed that, after warring with the Massagetae, they left Asia and entered the Crimean Peninsula. In literature, ‘Scythian’ increasingly became a derogatory term to describe savage and uncivilised people. Shakespeare refers to ‘The barbarous Scythian’ in King Lear; while Edmund Spenser sought to declaim the Irish by positing that they and the Scythians shared a common descent.

Alexander Pushkin used the term more warmly in his poetry, writing ‘Now temperance is not appropriate/I want to drink like a savage Scythian’; and in the Russia of the late nineteenth century, it came to be used to infer those qualities of the Russian people which marked them apart from Western Europeans. Abetted by archaeological excavations of Scythian kurgans (burial mounds) on Russian soil, a shared heritage with the Scythians was hypothesised as ‘Scythian’ became a byword for Russia’s historical past, Russian character, Russian otherness, and thereby also for Russia’s future.

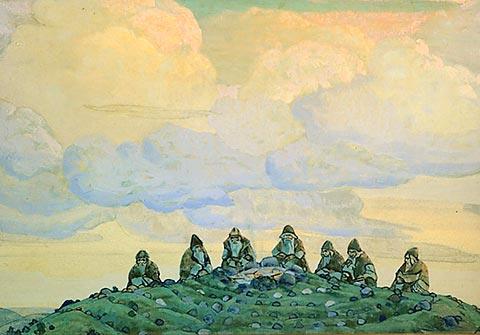

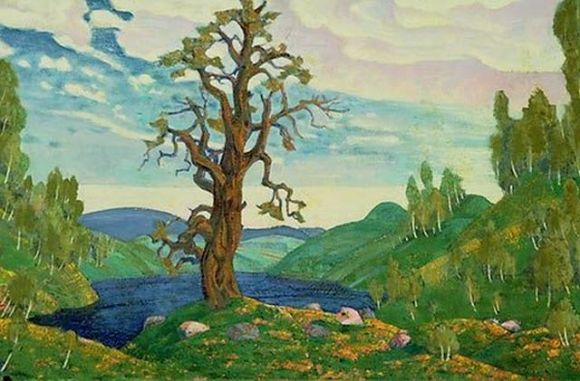

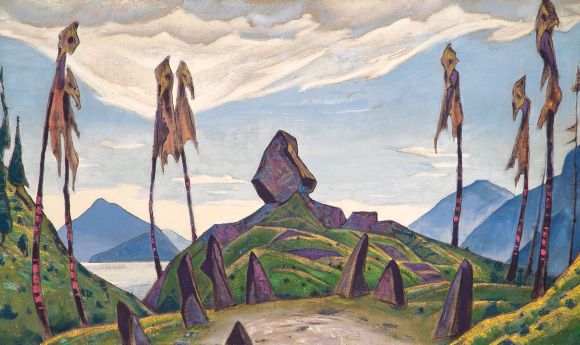

Emphasising the conflux of Eastern influences in The Rite of Spring, Orlando Figes argues that Stravinsky’s ballet ought to be viewed particularly as a manifestation of this interest in all things Scythian. The painter Nicholas Roerich had initially trained as an archaeologist. He had worked with the archaeologist and orientalist Nikolay Veselovsky in excavating the Maikop kurgan in Maikop, Southern Russia, in 1897. The Maikop kurgan was dated as far back as the third millenium b.c., and revealed two burials, containing rich artifacts including a bull figurine made of gold. Roerich was an adherent of Stasov, and when he began work on a series of paintings depicting the early Slavs, he sought Stasov’s advice regarding ethnographic details. Stasov advised him that wherever there was a lack of local evidence, it was appropriate to use artistic and cultural details from the East since ‘the ancient East means ancient Russia: the two are indivisible’.

Though the specifics of his background and his orientalism were not entirely fluent with the group’s more worldly outlook, Roerich became an entrenched figure in Diaghilev’s World of Art movement. After designing the sets for The Polovtsian Dances – a ballet excerpted from Borodin’s opera Prince Igor, which featured during the Ballets Russes first season in 1909 – Roerich went on to work with Stravinsky on the concept, setting and costumes for The Rite of Spring.

The idea for The Rite of Spring had emerged by 1910; Petrushka, which premiered a year later, two years before The Rite of Spring‘s own premiere, was the product of a very different core of people. While Diaghilev quickly became the prominent figure in the movement – owing to his bold entrepreneurial personality; his appetite for and ability to synthesise knowledge; and driving the publication of the magazine of the same name from 1899 – the World of Art (‘Mir iskusstva’ (Мир иску́сств)) originally comprised a group of Petersburg students around Alexandre Benois and Léon Bakst. Mirsky describes Benois as ‘the greatest European of modern Russia, the best expression of the Western and Latin spirit. He was also the principal influence in reviving the cult of the northern metropolis and in rediscovering its architectural beauty, so long concealed by generations of artistic barbarity…But he was never blind to Russian art, and in his work…Westernism and Slavophilism were more than ever the two heads of a single-hearted Janus’.

The World of Art embodied these two poles, and was part of the energetic and diverse avant-garde in Russia in the first decade of the 1900s. This avant-garde also included the Symbolists in literature, and Alexander Scriabin in music – an influential composer who experimented with forms of atonal music, and who was much loved by Stravinsky. After Diaghilev’s successes staging Russian opera and music in Paris towards the end of the decade, the Ballets Russes was formed. Bakst produced scenery for the company’s adaptation of Scheherazade in 1910; while Benois designed the sets for many of its earliest productions. He worked especially on Petrushka. Mirsky suggests that not only the set design but the very idea of the ballet ‘belongs to Benois, and once more he revealed in it his great love for his native town of Petersburg in all its aspects, classical and popular’. Both Scheherazade and Petrushka were choreographed by the established dancer and choreographer Michel Fokine.

When it comes to locating the genesis of The Rite of Spring, Lawrence Morton has asserted the probable influence on Stravinsky of Sergey Gorodetsky’s mythological poetry collection Yar. Stravinsky set two of Yar‘s poems to music between 1907 and 1908. He claimed that the idea for the ballet came to him as a vision, of a ‘solemn pagan rite’ in which a girl danced herself to death for the god of spring. Yet Roerich had written in 1909 an essay, entitled ‘Joy in Art’, which depicted ancient Slav spring rituals of human sacrifice. Figes argues the concept for the ballet was originally Roerich’s, and that ‘Stravinsky, who was quite notorious for such distortions, later claimed it as his own’; Thomas F. Kelly, in writing a history of the ballet’s premiere, has argued much the same thing.

Whatever, by May 1910 Stravinsky and Roerich were discussing together their ideas for the ballet. A provisional title, ‘The Great Sacrifice’, was quickly decided upon. Stravinsky spent much of the next year working on Petrushka. Then in July 1911, he visited Roerich at Talishkino, an artist’s colony presided over by the patron Princess Maria Tenisheva, where the scenario for the Rite – ‘a succession of ritual acts’ – was fully plotted out.

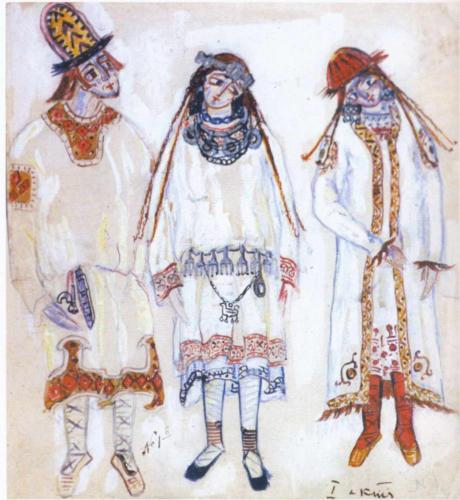

Figes considers that the ritual which the ballet explicitly evokes may have been based on Roerich’s archaeological research, during which he had found some evidence of midsummer human sacrifice among the Scythians. The switch from summer to spring was motivated partly by an attempt to link the rite to traditional Slavic gods; and ‘was also based on the findings of folklorists such as Alexander Afanasiev, who had linked these venal cults with sacrificial rituals involving maiden girls’. While Stravinsky composed the ballet, Roerich worked on the sets and costumes, which were rich in ethnographic details: drawing from his archaeological studies, from medieval Russian ornament, and from collections of traditional peasant dress.

The controversy of the ballet’s premiere in Paris is often conceived as Stravinsky’s. He wrote in his autobiography of the mockery of some members of the audience upon hearing the opening bars of his score, which built upon Lithuanian folk songs; and the orchestra were littered with projectiles as they performed. Other critics, however, have forwarded Roerich’s costumes as the ballet’s most shocking aspect. Others still, including the composer Alfredo Casella, felt that it was Vaslav Nijinsky’s choreography which most drew the audience’s ire. Figes writes:

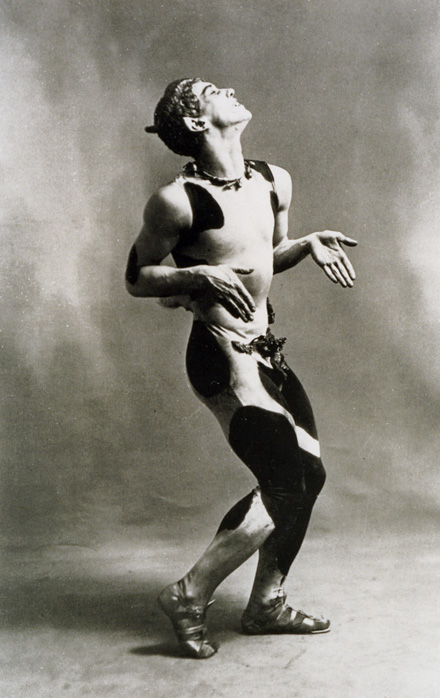

‘the music was barely heard at all in the commotion…Nijinsky had choreographed movements which were ugly and angular. Everything about the dancers’ movements emphasised their weight instead of their lightness, as demanded by the principles of classical ballet. Rejecting all the basic positions, the ritual dancers had their feet turned inwards, elbows clutched to the sides of their body and their palms held flat, like the wooden idols that were so prominent in Roerich’s mythic paintings of Scythian Russia.’

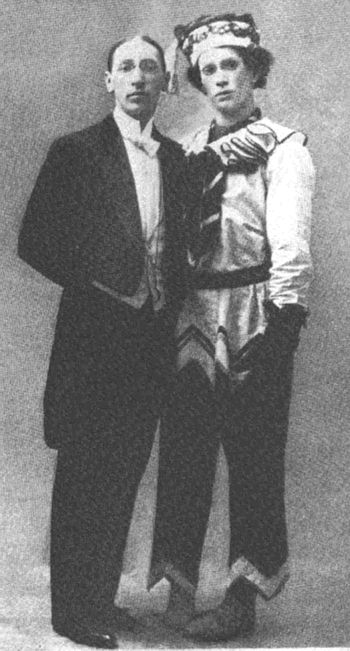

Nijinsky had been a leading dancer for the Ballets Russes since 1909. His first choreographic enterprise came with L’après-midi d’un faune, based on music by Debussy, which premiered in 1912. This debut choreography proved controversial: among mixed responses to the ballet’s premiere, Le Figaro‘s Gaston Calmette wrote, in a dismissive front-page review, ‘We are shown a lecherous faun, whose movements are filthy and bestial in their eroticism, and whose gestures are as crude as they are indecent’. Nijinsky’s second choreographic work, again after Debussy, was Jeux, which premiered just a couple of weeks before The Rite of Spring.

Nijinsky and Diaghilev had become lovers after first meeting in 1908. In the aftermath of Nijinsky marrying Romola de Pulszky in September 1913, while the Ballets Russes – without Diaghilev – toured South America, Diaghilev fired Nijinsky from his company. He reappointed Michel Fokine as his lead choreographer, despite feeling that Fokine had lost his originality. Fokine refused to perform any of Nijinsky’s choreography. A despairing Stravinsky wrote to Benois, ‘The possibility has gone for some time of seeing anything valuable in the field of dance and, still more important, of again seeing this offspring of mine’.

When Fokine returned to Russia upon the onset of World War I, Diaghilev began to negotiate for Nijinsky to return to the Ballets Russes. However, Nijinsky was in Vienna, an enemy Russian citizen under house arrest, and his release was not secured until 1916. In that year, Nijinsky choreographed a new ballet, Till Eulenspiegel, and his dancing was acclaimed; but he was showing increasing signs of the schizophrenia that would rule the rest of his life, and he retired to Switzerland with his wife in 1917. Without Nijinsky to offer guidance, the Ballets Russes were incapable of reviving his choreography for The Rite of Spring. His choreography was considered lost until 1987, when the Joffrey Ballet in Los Angeles performed a reconstruction based on years of painstaking research. Meanwhile, after the 1913 premiere, Stravinsky would continue to revise his score over the next thirty years.

Nicholas Roerich is perhaps best known today for his own paintings, for his spirituality, and for his cultural activism. His interest in Eastern religion and in the Bhagavad Gita flourished through the 1910s, inspired in part by his reading of the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore. Emigrating to London in 1919, then to the United States in 1920, in 1925 Roerich and his family embarked on a five-year expedition across Manchuria and Tibet. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize several times; while the Roerich Pact – an inter-American treaty signed in Washington in 1935 – established legally the precedence of cultural heritage over military defence. His art and his life is celebrated by the Nicholas Roerich Museum, which holds more than 200 of his paintings, located on Manhattan’s Upper West Side.

________

Figes, O. Natasha’s Dance: A Cultural History of Russia (London; Penguin, 2003)

Gibian, G. (ed.) The Portable Nineteenth Century Russian Reader (Penguin, 1993)

Mirsky, D. S. A History of Russian Literature (London; Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1968)