Pierrot, the sad clown, with white face and loose white blouse, expressing slowly and subtly and in the absence of and beyond words, emerged in the nineteenth century from his roots in stock comedies and pantomimes to become the embodiment of a certain artistic type, a specific strain of artistic emotion: sensitive, melancholy and solitary, and at once playful and daring in subverting language and suggesting the fraught but still facile and fluctuating nature of gender.

The character of Pierrot can be traced back to Molière’s Don Juan, or The Feast with the Statue, first performed in February 1660 at the Palais-Royal theatre in Paris, and with Molière playing the role of Sganarelle. Pierrot is the name of a peasant character who appears in the second act of the play, the fiancé of Charlotte. The Palais-Royal theatre had been established by Cardinal Richelieu, in the east wing of the Palais-Royal, in 1637; and by 1662, Molière’s acting troupe was sharing the venue with a troupe of Italian Commedia dell’Arte performers, including Domenicio Biancolelli, famous for his performances in the role of Harlequin. The Italian Commedia dell’Arte flourished throughout the seventeenth century in France, and in fact the character of Molière’s Sganarelle already drew from the Italian comedians. With Molière and Biancolelli’s troupes in such proximity, this interplay and cross-pollination continued, the Commedia dell’Arte incorporating Pierrot into its repertoire and well establishing the figure by the time of the Italians’ expulsion from France, by Royal decree, in 1697.

So Pierrot persisted on in Italy, and then again in France after Italian troupes were permitted to return during the second decade of the following century. Through the 1700s, though the character began to appear in performances in European centres outside of Italy and France, the Pierrot on display often featured in lesser and disparate roles: the basis of the character, his unrequited love for Columbine, who prefers Harlequin, was sometimes lost, and he was frequently portrayed in a purely comic, or even bumbling and foolish manner. It was in the 1800s that Pierrot gained stature, and began his reach into the other arts, developing in literature and painting as an emblem and as a muse.

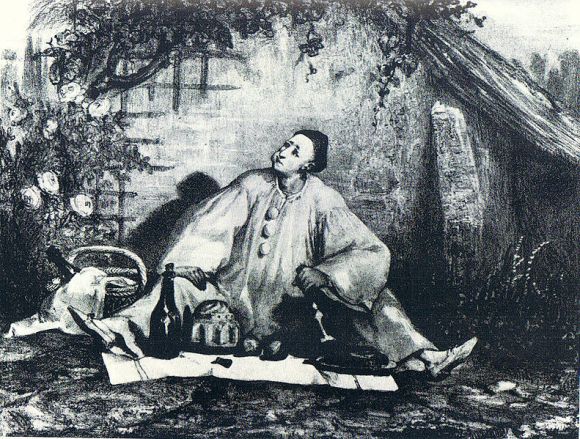

Jean-Gaspard Deburau, a mime from Kolín, in what is now the Czech Republic but was then Bohemia, was most responsible for this recreation of Pierrot. Born in 1796, he began appearing in Paris at the Théâtre des Funambules some time around 1819, under the stage-name ‘Baptiste’. The Funambules had opened in 1816, on the Boulevard du Temple, otherwise known as the Boulevard du Crime owing to the volume of crime dramas shown nightly in the Boulevard’s numerous theatres – all but one of which, including the Funambles, were demolished during Haussmann’s rebuilding of Paris in the 1860s. The Funambules originally hosted only acrobats and mimes; and Deburau, taking the role of Pierrot as a young man, would continue at the part until his death in 1846. He extended and deepened Pierrot, his restrained and nuanced acting style replacing the tendency towards bold and gesticulating comedy; gaining recognition and increasing fame towards the end of the 1820s, Deburau’s Pierrot would even be compared to the works of Shakespeare when, in 1842, the versatile and distinctly modern man-of-letters Théophile Gautier wrote a fictionalised review entitled, ‘Shakespeare at the Funambules’.

Other mimes would continue to have success playing Pierrot after Deburau’s death. These included his son, Jean Charles, and most notably Paul Legrand. Still, it was Deburau who enshrined Pierrot within French culture, and established the sense of Pierrot as a sensitive and anguished artist. This conception of Pierrot was celebrated, explored and entrenched in 1945 with Marcel Carné’s film, Les Enfants du Paradis, often considered one of the greatest films of all time; which suffered its own anguishes as it was made in occupied France, with damaged sets, short of supplies, with a cast and crew short of food and comprising several Jews who had to work secretely or risk production shutting down; and consisting of a fictionalised story drawing upon real figures from early nineteenth century France. Deburau is portrayed in the film as ‘Baptiste’, a lovelorn mime who achieves success in the Funambules, in a magnificent performance by Jean-Louis Barrault.

Gautier’s piece on Deburau’s Pierrot was but one of the first entwinements of Pierrot with literature. Writers including Flaubert (who, early in his career, wrote an unperformed pantomime entitled Pierrot au sérail), Verlaine and Huysmens incorporated Pierrot into their works. Most extensively, he was the central figure in the poetry of Jules Laforgue. Laforgue – a French Symbolist poet who died in 1887 aged just twenty-seven years old – wrote three of the ‘complaints’ in his first selection of poems, Les Complaintes (1885), in Pierrot’s voice; then devoted his second collection, L’Imitation de Notre Dame de la Lune (1886), entirely to Pierrot and his moonlit world, influenced by Albert Giraud’s poetry cycle published a couple of years previously.

In his book, The Symbolist Movement in Literature, first published in 1899, which served to introduce French Symbolism to an English readership, Arthur Symons devoted a chapter to Laforgue. Symons describes Laforgue’s verse and prose as,

‘alike a kind of travesty, making subtle use of colloquialism, slang, neologism, technical terms, for their allusive, their factitious, their reflected meanings, with which one can play, very seriously. The verse is alert, troubled, swaying, deliberately uncertain, hating rhetoric so piously that it prefers, and finds its piquancy in, the ridiculously obvious…It is an art of the nerves, this art of Laforgue, and it is what all art would tend towards if we followed our nerves on all their journeys.’

and defines Laforgue’s laughter in the following terms:

‘His laughter, which Maeterlinck has defined so admirably as ‘the laughter of the soul’, is the laughter of Pierrot, more than half a sob, and shaken out of him with a deplorable gesture of the thin arms, thrown wide. He is a metaphysical Pierrot, Pierrot Lunaire, and it is of abstract notions, the whole science of the unconscious, that he makes his showman’s patter.’

Laforgue was a great influence upon a young T. S. Eliot. Later in his life, Eliot would write that, ‘Of Jules Laforgue I can say that he was the first to teach me how to speak, to teach me the poetic possibilities of my own idiom of speech’, and, ‘I have written…nothing about Jules Laforgue, to whom I owe more than to any one poet in any language’. In this way the figure of Pierrot maintained a relevance beyond French Romanticism and Symbolism, on into the literature of the Anglophone Modernists. He also appeared in canvases by painters who led their art-form into modernity: in Seurat’s Pierrot with a White Pipe (1883); in Cézanne’s Pierrot and Harlequin (1888); whilst Picasso’s Pierrot and Columbine (1900) was the first of several pieces in which he depicts Pierrot.

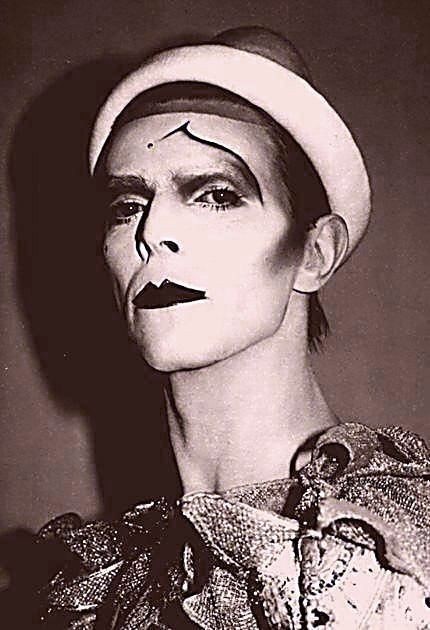

Pierrot became a canonised figure within twentieth century classical music with Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21, a setting of twenty-one poems from a German translation of Albert Giraud’s cycle. Schoenberg’s work was premiered in Berlin, on 16 October, 1912, with Albertine Zehme the solo vocalist. Theodor Adorno, theorist, philosopher and musicologist, wrote some of his earliest pieces on Schoenberg; including a 1922 review of a performance of Pierrot Lunaire in Frankfurt, in which Adorno puts it that Schoenberg’s piece characterises ‘the homelessness of our souls’. Musically and aesthetically, Pierrot has exerted his influence too on popular music: Björk, a fervent admirer of Schoenberg, sang Pierrot Lunaire in a one-off performance at the Verbier Festival in 1996; whilst David Bowie, after studying theatre and mime, played a role in the 1967 theatrical production Pierrot in Turquoise, and appeared as Pierrot in the video to his 1980 song, ‘Ashes to Ashes’.

____________

Jean-Louis Barrault in Les Enfants du Paradis

Jean-Louis Barrault in Les Enfants du Paradis

____________

Jules Laforgue – ‘Autre Complaint de Lord Pierrot’ (‘Another Complaint of Lord Pierrot’). In French; then translated into English courtesy of Paul Staniforth and brindin.com

——–

Celle qui doit me mettre au courant de la Femme!

Nous lui dirons d’abord, de mon air le moins froid:

“La somme des angles d’un triangle, chère âme,

Est égale à deux droits.”

–

Et si ce cri lui part: “Dieu de Dieu! que je t’aime!”

– “Dieu reconnaîtra les siens.” Ou piquée au vif:

– “Mes claviers ont du coeur, tu seras mon seul thème.”

Moi: “Tout est relatif.”

–

De tous ses yeux, alors! se sentant trop banale:

“Ah! tu ne m’aimes pas; tant d’autres sont jaloux!”

Et moi, d’un oeil qui vers l’inconscient s’emballe:

“Merci, pas mal; et vous?”

–

– “Jouons au plus fidèle!” – “à quoi bon, ô Nature!

Autant à qui perd gagne!” Alors, autre couplet:

– “Ah! tu te lasseras le premier, j’en suis sûre…”

– “Après vous, s’il vous plaît.”

–

Enfin, si, par un soir, elle meurt dans mes livres,

Douce; feignant de n’en pas croire encor mes yeux,

J’aurai un: “Ah! ça, mais, nous avions De Quoi vivre!

C’était donc sérieux?”

——–

The one who’ll give an update on her sex!

We’ll tell her first in our least frigid air

“The sum of a triangle’s angles makes

exactly two right angles, dear.”

–

And should she peal “O God! how I love you!”,

‘God’ll know his own’ – or, cut to the quick:

“My heart knows love’s keys; I’ll play but of you!”,

then I: ‘All’s relativistic.’

–

Then, with all eyes, feeling too commonplace

“You don’t love me whom men crave with each muscle?”

And I, with an eye on Unconsciousness,

‘Oh, not so bad, ta, and yousel’?’

–

“Let’s vie in fidelity!” – ‘Might as well play

(Nature!) loser wins.’ And after those, these:

“Oh, you’ll tire of me first, you’ll go away…”

‘Oh no: ladies first, if you please.’

–

Last, if one night she die in my ‘Divan’,

soft … with fake disbelief in my closet

I’ll go ‘Well, now, we’d something to live on –

it was serious then, was it?’

____________

Pierrot with a White Pipe, by Seurat

Pierrot with a White Pipe, by Seurat

____________

![Pierrot and Harlequin [Mardi-Gras] (1888-1890) - Paul Cezanne - Gallery of European and American Art - Moscow Musts](https://culturedallroundman.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/cezanne-pierrot-and-harlequin.jpg?w=467&h=580) Pierrot and Harlequin, by Cézanne

Pierrot and Harlequin, by Cézanne

____________

Pierrot and Columbine, by Picasso

Pierrot and Columbine, by Picasso

____________

Schoenberg’s Pierrot Lunaire, Op. 21

____________

____________

Raine, C. T. S. Eliot (Oxford University Press, 2006)

Symons, A. The Symbolist Movement In Literature (Dutton & Company, 1919)

Wiggerhaus, R. The Frankfurt School: Its History, Theories, and Political Significance (MIT Press, 1995)