With the situation in Crimea apparently resolved, at least for the time being, attention is turning to other sites in Ukraine and beyond. The withdrawal of Ukrainian forces at the beginning of this week – after Russian troops seized the Belbek airbase and Feodosia naval base – marked the interim Ukrainian government’s tacit acceptance that Crimea has been lost. Russian military action in the region following the Crimean referendum on 16 March has been efficient – threatening rather than violent, utilising unidentified pro-Russian groups to storm bases, backed up by official military personnel – as a lack of explicit direction from Kiev has left Ukrainian troops seemingly little more than caretakers, waiting for Crimea to pass into Russian hands. Six of the eleven senior Ukrainian officers held by Russia following these takeovers have now been released. Meanwhile, following the assent of the Crimean parliament, the city council of Sevastopol, and Vladimir Putin, both the Federation Council and the State Duma have ratified Crimea’s integration into the Russian Federation. Two Crimean senators are scheduled to join Russia’s Federation Council from 16 April.

Across the West, the international community continues to decry Russia’s intervention in Crimea, and will not accept the legitimacy of Crimea’s separation from Ukraine. A symbolic vote in the UN on Thursday saw 100 countries affirm that the Crimean referendum took place illegally; 11 countries disagreed, while 58 abstained. The US, Canada, the United Kingdom, Germany, France, Italy and Japan have opted to temporarily suspend Russia from the G8 group of nations, and will continue to meet without Russia, reverting to the G7. Russia has described this as ‘no great tragedy’; while other commentators, including former German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt, have dismissed this and other sanctions as ineffective, stressing that the G8 has been superseded as an economic forum by the G20, which incorporates emerging economies and still includes Russia.

There is a certain pragmatism in all parties accepting the current state of affairs in Crimea. Putin has achieved a show of force, asserting his position back home and emboldening nationalist sentiment, while bolstering Russia’s military authority across the Crimean peninsula. As things stand, Ukraine has maintained the territorial integrity of its mainland, and the ability to move towards presidential elections and constitutional reform come May. The sanctions imposed by the EU, the US and Canada will continue to be decried as weak, especially by those on the right of politics; but they went perhaps further than expected in targeting some prominent Russian officials and businessmen. Both Ukraine and the West must really content themselves with their mutual sympathies, and with Russia’s loss of international sway, given the impracticality of attempting to keep Crimea as part of Ukraine. While Ukraine’s interim Prime Minister, Arseniy Yatsenyuk, has stressed that the country’s financial position remains perilous, the International Monetary Fund has promised it $18 billion in loans – which, for good or ill, will provide the IMF and its backers with significant influence over the country’s future economic development. The US Congress has guaranteed a $1 billion loan of its own, plus $150 million in direct aid. It is the Crimeans themselves who have arguably lost the most, in so far as they have been forced to choose between Russia on the one hand and Ukraine and the EU on the other; but the choice they have made seems clear, and it enables them to retain their crucial economic and close cultural ties with Russia.

Still, what spoke for the Russians restraining their ambitions, and embarking on a lesser show of force in order to secure only military access to Crimea – while leaving the region perhaps with greater autonomy from Ukraine, but still politically part of the country – was that it would have maintained Russia’s influence over Ukraine, ideologically and electorally. Russia will not settle gladly for an antagonistic Ukraine: it values its economic role in the country; their shared cultural bonds; and Russia has always protected itself in terms of land, seeking to maintain buffer regions between its capital and the outposts of its supposed enemies. But Putin perhaps presumes that by manipulating tensions in eastern Ukraine when it suits, and owing to Ukraine’s financial dependence on Russia, especially when it comes to gas, Ukraine can scarcely afford to sever their relationship completely.

It is to Ukraine’s east that attention has now turned. Ukraine and the West allege that Russia is poised to launch an invasion into eastern Ukraine, which has seen a wave of demonstrations since the ousting of President Yanukovych towards the end of last month. The region has a significant ethnic Russian populace, and its economy is reliant on Russian trade. A history of separatist feeling in the east extends back to the foundations of the Ukrainian state. Russia has carried out military exercises on the Ukrainian border, but the extent of its interest in eastern Ukraine is hard to gauge amid inevitable claim and counterclaim. Russia asserts that it has no desire to divide Ukraine, and argues that violence in the east has been incited by far-right Ukrainian nationalists and by American defence contractors. Ukraine and the US suggest instead that Russian soldiers have infiltrated the east, that pro-Russian protesters are being transported across the border into Ukraine, and that Russia is amassing its military with intent. NATO’s Supreme Allied Commander Europe, Philip Breedlove, has raised additional concerns that Russian forces could sweep through southern Ukraine into neighbouring Transdniestria, which broke away from Moldova in 1990 as the Soviet Union began to fall, but has never been given international recognition. The half-million population of Transdniestria is evenly split between Moldovans, Russians, and Ukrainians. Russia has continued, since Moldovan independence in 1992, to maintain a contested military presence of 1,200 troops in the region. Fears over Russian incursions into the Baltic states appear at this point unfounded, and would be impeded by their memberships of the EU and NATO.

————

Following my history of Crimea – which summarised the course of the region until its absorption into the Russian Empire in the 1700s; from which I looked at events in Crimea in more depth, through the eyes of Pushkin, Tolstoy, Chekhov, and Nabokov – what proceeds is a brief but involved history of Ukraine. It begins in the early middle ages, with Kievan Rus as a loose federation of the East Slavic peoples. Taking a paragraph from my earlier piece:

Kievan Rus flourished from about 882 – when Prince Oleg moved the capital of the Rus from Novgorod to Kiev – until the 13th century, when the Mongol Empire invaded and destroyed their major cities. While Russia gradually threw off the ‘Mongol-Tatar Yoke’, and began to emerge round the city of Moscow as a powerful independent state, Kiev and much of what is now northern and central Ukraine came under Polish-Lithuanian control. The Russo-Polish War of 1654-1667 ended in a truce, but one which forced the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth to relinquish Kiev and the lands east of the Dnieper River (plus Smolensk further north) to the Tsardom of Russia. These lands continued to rule themselves with some autonomy for the next hundred years, the period of the Cossack Hetmanate; but this autonomy was successively diminished during the reign of Catherine the Great (1762-1796), and the region came to be fully incorporated into the Russian Empire. Russia often considers the union between Kiev and Moscow to extend back to the beginnings of the the Russo-Polish War in 1654.

The partitioning of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in the late 1700s added to the Russian Empire the lands west of the Dnieper. Together, the lands won from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth between 1654 and the end the 18th century would come to comprise much of modern mainland Ukraine. With the span and diversity within the enlarged Russian Empire, the concept of an All-Russian nation was promulgated as an attempt to unify its collected peoples under one state. The concept recognised the differences between the peoples of modern-day Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, but endeavoured to subsume them, positioning them as deviations which obscured a fundamental cultural and historical unity.

Nevertheless, within the Russian Empire the people spread east and west of the Dnieper came to be called Little Russians, while the region was referred to as Little Russia (‘Малороссия’, Malorossiya). These labels were readily embraced by those wealthy members of the populace who quickly rose to positions of prominence within the Empire. However, the larger population identified instead as Ruthenian – a historical term for the East Slavic people who lived in an area between modern west-Ukraine and Poland, broadly equivalent with the geographic territory of Galicia. This larger population of the region maintained a common language discrete from Russian: while both were rooted in Old East Slavic, which had been established during the period of Kievan Rus, the language they spoke had developed differently, owing to internal forces and to the influence of Polish-Lithuanian rule.

Fearful that nationalist sentiment would emerge among their ‘Little Russians’, in the early 1800s the Russian Empire banned the use of the regional language and enforced Russian as the language of political administration and education. Nationalist sentiment still arose, notably in Kiev, where in the middle of the 1840s it grew around the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius. This secretive nationalist political society had as one of its party the poet Taras Shevchenko. Born on 9 March 1814 in Moryntsi, a couple of hundred kilometres south of Kiev, Shevchenko moved to Saint Petersburg in 1831, and towards the end of the decade enrolled there in the Academy of Arts. Painting landscapes, portraits and rural idylls, he began writing poetry in the language of his homeland. His first collection, Kobzar, was published in 1840.

Shevchenko visited the regions of ‘Little Russia’ on several occasions in the following years; then in 1847, he was arrested, preliminarily owing to his connection with the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius. As an artist rather than an activist, he was set to escape severe punishment, until Emperor Nicholas I uncovered one of his poems which mocked both the Emperor and his wife. Shevchenko was imprisoned in Petersburg, then exiled to Orsk near the Ural Mountains, where he would spend the next decade. After a further two years in Nizhniy Novgorod, in May 1859 he was finally allowed to return to Kiev; but this respite proved short lived, for in July he was arrested again, remaining in Petersburg until his death on 10 March 1861. Buried initially in Petersburg, his remains were transported by his friends to a hill on the banks of the Dnieper River, near Kaniv.

Shevchenko is esteemed today as Ukraine’s national poet; the anniversary of his birth celebrated several weeks ago was the occasion of marked clashes between opposing groups in Crimea and eastern Ukraine. His poetry is considered foundational in the development of Ukrainian literature, and influential too in the emergence of the modern Ukrainian tongue. As he wrote in the regional language, and expressed nationalist views in a number of his works, to call Shevchenko a Ukrainian poet seems entirely warranted. In the case of Nikolai Gogol – the most famous of writers born on Ukrainian soil – attempted recastings of him as a Ukrainian writer remain controversial, open to the charge of anachronism. Gogol was born on 31 March 1809 in Sorochyntsi, on the left-bank of the Dnieper, and grew up in a family that spoke both Russian and the regional language. He moved to Saint Petersburg in 1828, then travelled abroad in 1836, spending most of the next twelve years in Rome. After returning to the Russian Empire in 1848, via a curtailed pilgrimage to Jerusalem, he died in Moscow on 4 March 1852.

Gogol drew for his earliest stories from Ukrainian settings, customs, folklore, and theatre. His first collections of short stories – Evenings on a Farm Near Dikanka, published in two volumes in 1831 and 1832, and Mirgorod, published in 1835 – are set with fondness in the rural ‘Little Russia’ of his youth. Working on these in Petersburg, Gogol would write home for points of detail on which to elaborate his fiction. He maintained until his final years friendships with scholars of Ukrainian language and history, who shared friendships also with Shevchenko. At the same time, Gogol wrote solely in Russian. His mature stories are set predominantly in Petersburg. According to Gogol, several of them took their plot from ideas given to the author by Pushkin. The loosely political sentiments which may be derived from Gogol’s letters and his notoriously peculiar Selected Passages from Correspondence with Friends, published in 1847, speak towards a vaguely pan-Slavic spiritual identity, conceived as Russian, rather than to any nationalist movement. He would write:

‘We Little Russians and Great Russians need a common poetry, a calm, strong and everlasting poetry of truth, goodness and beauty. The Little and the Great Russian are the souls of twins who complement each other, who are closely related and equally strong. It is impossible to prefer one of them at the cost of the other.’

Gogol’s art was adopted so wholly into the great body of Russian literature which followed, from Dostoevsky to Bely to Nabokov – three of his most perceptive interpreters – that disengaging him from this mainstream of Russian letters proves difficult, and would appear to bear relatively little fruit. On the other hand a full understanding of his art must contemplate its distinctly Ukrainian beginnings. Whatever, unlike Shevchenko, Gogol today is not regarded in any way a symbol of Ukrainian statehood.

While national sentiment began to grow on the banks of the Dnieper, it was not until the late 1800s that the concept of a ‘Ukrainian’ people – and of the word ‘Ukraine’ as the proper name for the region – began to appear. This marked a rejection of the diminutive ‘Little Russian’ and of the historical term ‘Ruthenian’, considered insufficient to represent the sense and the aims of the emerging nationalist movement. The word ‘ukraina’ had been used from the 1500s to essentially mean ‘borderland’: derived from the Proto-Slavic ‘krajь’, meaning border or edge, the term had referred to the frontiers of the Kingdom of Poland in and around Kiev. It was used informally to denote the region during the rule of the Cossack Hetmanate. By the 1840s, the Brotherhood of Saints Cyril and Methodius were calling the people of the region ‘Ukrainians’ – though the appellation was never adopted by Shevchenko, who used ‘Little Russian’ even in his nationalist texts. By the turn of the century, the usage ‘Ukrainian’ was entrenched among nationalists, and referred to themselves as a distinct ethnic group. The usage would only become standard beyond the banks of the Dnieper over the next two decades.

Politically, Ukraine’s existence as an independent state can be traced back to 1917 and the February Revolution which effectively marked the end of the Russian Empire. Within days of the Provisional Government under Alexander Kerensky forming in Saint Petersburg (then called Petrograd), the nationalist movement in Kiev consolidated and established a central council, called the Tsentralna Rada. The Tsentralna Rada issued an early declaration calling on ‘the Ukrainian people’ to support Kerensky’s Provisional Government. It then elected the prominent nationalist academic Mykhailo Hrushevskyi as its head, and formed a parliament of 150 which effectively began administering Ukrainian affairs. Towards the end of June, after back-and-forth with Kerensky, the Rada issued its ‘First Universal’, declaring Ukrainian autonomy as part of the Russian Republic. A Ukrainian government was formed, called the General Secretariat and comprising nine ministers, and it was recognised by Kerensky.

Disagreements between the Provisional Government in Petrograd and the Tsentralna Rada regarding the degree of autonomy the General Secretariat should possess were rendered irrelevant following the October Revolution, which saw the Bolsheviks seize power in Petrograd. Initially maintaining relations with the Bolsheviks, in November the Rada, via another ‘Universal’ decree, proclaimed the Ukrainian People’s Republic. The extent of the autonomous state’s jurisdiction was also defined: it would govern over the majority of the regions which comprise modern Ukraine, including the Kharkiv region, but not including Crimea. As relationships with the Bolsheviks broke down, and with the Bolsheviks setting up base in Kharkiv, in late January 1918 the Tsentralna Rada issued its ‘Fourth Universal’, declaring the full independence of the Ukrainian People’s Republic.

The Bolsheviks had continued to press within the newly emerged state. Regions within the Ukrainian People’s Republic were encouraged to break away, and to establish their own Soviet republics. Lacking a strong military capacity, the Ukrainian People’s Republic sought foreign aid, turning to the Russian Empire’s opponents in the ongoing First World War, the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary. The first treaty of Brest-Litovsk, signed by the Ukrainian People’s Republic and the Central Powers on 9 February, in theory secured Ukrainian sovereignty, but in practise made the Republic a German protectorate. Amidst Ukrainian resentment, on 29 April a German-backed coup saw the Tsentralna Rada dismissed and a former Russian General, Pavlo Skoropadskyi, installed as the state’s new ruler.

Skoropadskyi styled himself Hetman of Ukraine. Where under Hrushevskyi’s leadership the Tsentralna Rada had been broadly socialist, the new Hetmanate was conservative. When it too fell following the defeat of the Central Powers in World War I in November, a socialist Directorate was formed to govern; but within a month, fighting broke out as the Republic became fully embroiled in the Russian Civil War. At the same time, Austria’s defeat saw its province of Galicia become divided between the claims of Ukrainians and Poles. Ukrainians in the region proclaimed the West Ukrainian People’s Republic days before the restoration of the Polish state on 11 November 1918. On 22 January 1919, a Unification Act was signed between the West Ukrainian People’s Republic and the Ukrainian People’s Republic in Kiev. The Polish-Ukrainian War over Galicia lasted until July, and ended in a Polish victory.

Meanwhile Ukraine saw battle between the Soviet Red Army and the anti-Bolshevik White Army, and authority in Kiev fluctuated back and forth between the Ukrainian People’s Republic and the Bolsheviks. By the spring of 1920, the Ukrainian People’s Republic was again in desperate need of foreign intervention, and now allied with Poland, whose forces over the coming months repelled the Bolshevik advance. A decisive Polish victory at the Battle of Warsaw in August forced Soviet Russia to sue for peace. The drawing to a close of Polish-Soviet hostilities, allied to General Wrangel’s defeat in Crimea – the last bastion of the White Army – in November, effectively ended the Russian Civil War. The Treaty of Riga – signed between Poland and Soviet Russia on 18 March 1921 – ensured for Poland Galicia and a significant area of western Ukraine; while Soviet Russia established control over the central and eastern Ukrainian mainland. Poland’s victory in the Polish-Soviet War was crucial in the development of 20th century Europe: beyond securing the status of Poland, it is perceived as halting Soviet ambitions towards ‘international revolution’, the spreading of communist revolution by force. The Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic – Soviet Ukraine – was confirmed, and inaugurated as part of the Soviet Union on 30 December 1922.

Power in the Soviet Union was centralised by Stalin in Moscow, and nationalist sentiment in the Soviet Republics was suppressed. The Holodomor of 1932-33 saw from 2 million to as many as 7 million Ukrainians die of starvation, owing to famine. It remains contentious whether the famine was a product of negligent economic policy, in the period of rapid Soviet industrialization and forced collectivisation; or whether it was in fact deliberately engineered, thereby constituting a genocide of the Ukrainian people. At the close of World War II, the Soviet Union would retain those Polish regions adjoining Soviet Ukraine which it had annexed during the war. It thus regained all of the western territories which Ukraine had lost by the Treaty of Riga in 1921: including, most controversially, Lviv, the old capital of Galicia. Ukraine would gain its independence following the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, in a process depicted in my most recent post.

————

While the above deals with western Ukraine and the formation of the Ukrainian state, it is necessary to consider in more detail the major cities of eastern Ukraine. Many of the major cites of today’s south-eastern Ukraine once comprised the Yekaterinoslav Governorate, established in the Russian Empire in 1802, and continuing in its administration through until 1925. The Yekaterinoslav Governorate included Yekaterinoslav – a city on the Dnieper which was renamed Dnipropetrovsk in 1926, and became closed to foreigners, serving as a centre of the Soviet arms and space industries – and extended east to the cities of Luhansk, Mariupol, and what would become Donetsk. Briefly, the Yekaterinoslav Governorate even took in Rostov-on-Don, deep into modern-day Russia; though the port of Taganrog remained outside the Governorate, with special city status and its own Governor. Taganrog and Rostov-on-Don would both become part of the Don Host Oblast in 1887, the precursor to today’s Rostov Oblast.

Donetsk traces its history to 1869, when a small settlement built up around a metal works developed by the Welsh industrialist, John Hughes. The settlement took the name ‘Hughesovka’, rendered Yuzovka, and grew rapidly as the metal works became one of the most productive in the Russian Empire. In 1917, Yuzovka was given the status of a city. During the Russian Civil War, it became part of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic. This was one of the self-proclaimed republics encouraged into fruition by the Bolsheviks: it sought to break from the fledgling Ukrainiain People’s Republic, and comprised the cities and towns of the Donets Basin, the cities of Yekaterinoslav and Luhansk, parts of the Kherson Governorate and the Don Host Oblast and, momentarily, also Kharkiv. Kharkiv then Luhansk served as the short-lived breakaway republic’s capital: established in early February 1918, it went unrecognised and collapsed the following month with the second treaty of Brest-Litovsk. This second treaty, signed between Soviet Russia and the Central Powers on 3 March, removed Soviet Russia from World War I, with the Central Powers ensuring that the Bolsheviks recognised the Ukrainian People’s Republic, by the time effectively a German protectorate.

As part of Soviet Ukraine, Yuzovka was renamed Stalin in 1924, then Stalino in 1928. In 1920, the Donetsk Governorate had been formed, taking from the Yekaterinoslav Governorate administrative control over the Donets Basin. In 1932 – following the transitional ‘okruha’ system of administration, which saw Soviet Ukraine’s Governorates subdivided into smaller districts – the Donetsk Governorate became the Donetsk Oblast. As the population of Stalino and of the wider region quickly grew – with the city building new tram lines, theatres and opera houses, and installing a water system in 1931 followed by a sewage system two years later – in 1938 the oblast was split into two, with the creation of the Stalino Oblast and the Voroshilovgrad Oblast. The Nazi occupation during World War II devastated the city’s development, and it was forced to rebuild. In 1961, Stalino became Donetsk.

Luhansk too traces its foundation to a British industrialist, growing out of a metal works established by Charles Gascoigne in 1795. Luhansk achieved city-status in 1882. It was renamed Voroshilovgrad in 1935, and became the centre of the oblast created in 1938. After suffering Nazi occupation during the war and rebuilding, the city was retitled Luhansk in 1958; Voroshilovgrad was restored as its name in 1970; and Luhansk reemerged again in 1990. Both Donetsk and Luhansk remain today important centres of industry, particularly in coal and steel.

Kharkiv in the north east has a longer past. The Cossack uprising which prefaced the Russo-Polish War of 1654-1667, and the civil war which continued until the ascension of Ivan Mazepa as Cossack Hetman in 1687, caused many to flee from the banks of the Dnieper. Settlers had formed what would become the city of Kharkiv by 1656. Voivodes were appointed by Moscow to govern the new settlement, and soon a fortress had been built to secure it from quarrelsome neighbours. The settlement grew into a city as part of the Russian Empire, establishing the University of Kharkiv in 1804 (the second oldest in Ukraine, after the University of Lviv), and acquiring running water in 1870. Throughout the 1800s it became an important centre of nationalist sentiment outside Kiev: a nationalist society was formed, and the city saw published the first newspaper in the Ukrainian language. The prominent nationalist Mykola Mikhnovsky gave a speech in Kharkiv in 1900 – during celebrations commemorating the anniversary of Taras Shevchenko – which would be published as the pamphlet ‘Independent Ukraine’. Mikhnovsky was the first to propound the idea of independent Ukrainian statehood, and was one of the founders of the Revolutionary Ukrainian party and the radical Ukrainian People’s party, which would propel the nationalist cause in the first decade of the 1900s.

After the Bolsheviks had used Kharkiv as their base of power during the Ukrainian War of Independence from 1917, and after its brief role as part of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic, Kharkiv served as the capital of Soviet Ukraine following its establishment, until the capital was transferred to Kiev at the end of 1934. The Kharkiv Oblast suffered severely during the Holodomor; and it was the site of major battles during World War II, as the city of Kharkiv passed between the Soviets and Nazi occupation. Much of the city was destroyed, and tens of thousands killed; including 30,000 people from the city’s sizeable Jewish minority. As the city was rebuilt, it became a centre of Soviet science and industry.

Today the cities of the east are some of the most populous in Ukraine. Kharkiv is the country’s second most-populous city, with 1.5 million inhabitants. After Odessa and Dnipropetrovsk, with about one million citizens each, Donetsk is fifth, with 960,000. Nearby Makiivka has a population of 360,000, and is merging with Donetsk as the two cities expand, forming a conurbation. Mariupol has a population of just under 500,000, including the largest Greek population in Ukraine, with more than 50,000 Greeks living in the area. 450,000 people live in Luhansk. The Luhansk Oblast is the easternmost oblast in Ukraine, with the Kharkiv Oblast immediately west, the Donetsk Oblast to the south-west, and the Rostov Oblast east, across the border in Russia. Comprising the cities of Donetsk, Mariupol and Makiivka, the Donetsk Oblast is Ukraine’s most populous. Where ethnic Russians make up about 17% of Ukraine’s total population – against 78% ethnic Ukrainians – in the east this overview is skewed: 44% in Kharkiv are ethnic Russian, 50 % ethnic Ukrainian; and in Donetsk, 48% are ethnic Russian, 47% Ukrainian. Again, the east is the industrial heart of Ukraine, and remains heavily dependent on the Russian economy, with which it carries out most of its trade.

While there have been smaller protests in Dnipropetrovsk, in Odessa, and in Mykolayiv (a shipbuilding city in the south), it is Donetsk, Luhansk and Kharkiv which have seen the strongest pro-Russian expression. These cities have seen protests gathering in excess of 10,000 people, as rival pro-Ukrainian and pro-Russian – or pro and anti-interim government, or pro and anti-Ukrainian far-right, or pro and anti-Yanukovych, or pro and anti-Putin – demonstrators have clashed, sometimes violently, amid the waving and hoisting of national and regional flags (the old flag of the Donetsk-Krivoy Rog Soviet Republic has made several appearances). At the beginning of March – compelled in part by the inclusion of members of Svoboda in the interim Ukrainian government, and by the proposed repeal of a law establishing Russian as an official second language – pro-Russian supporters took control of administrative buildings in Kharkiv and Donetsk. ‘People’s Governors’, calling for referendums on union with Russia, were elected in Donetsk and Luhansk. The proclaimed ‘People’s Governor’ of Donetsk, Pavel Gubarev, was arrested on 6 March by Ukraine’s Security Service, the SBU, charged with separatism. On 10 March, Mikhail Dobkin, the pro-Russian former Governor of Kharkiv Oblast and Mayor of Kharkiv, was also arrested by the SBU. The interim Ukrainian government has stated its hope to try such individuals at the International Criminal Court.

These conflicts turned bloody when, on 13 March, a pro-Ukrainian protester was stabbed to death in Donetsk, as rival groups fought on the city’s Lenin Square. On 15 March, two men – reportedly a pro-Russian protester and a passerby – were shot dead in Kharkiv, by a group of Ukrainian nationalists. Since then, and in the aftermath of the Crimean referendum, the situation in the east has calmed. Both Vladimir Putin and Sergei Lavrov, the Russian Foreign Minister, have repeatedly stressed no desire to invade or annex eastern Ukraine. In the speech he gave to both houses of the Federal Assembly last week – full of his own increasingly nationalistic rhetoric as Crimea’s integration with the Russian Federation moved a step closer – Putin asserted ‘we do not need a divided Ukraine’.

————

One of the most important facets of many major revolutions is the degree to which they have centred on capital cities. The French Revolution was spurred when – seeking to uphold the newly formed National Constituent Assembly, and fearful of the gathering foreign mercenaries who might fight to preserve the old regime – the people of Paris rioted and stormed the Bastille. The Russian revolutions of February and October centred entirely on Petersburg (then Petrograd): the former the result of a series of protests culminating on International Women’s Day; the latter achieved when the Bolsheviks seized an empty Winter Palace, from which proceeded the Russian Civil War. In a related vein, whatever one terms the culmination of events in Ukraine last month – whether they constituted a revolution, an uprising, or a coup – the impetus for the ousting of President Yanukovych was in Kiev. The public feeling and the political machinations displayed there were not acutely representative of the shades of feeling elsewhere in the country.

Given the situation in Kiev – the removal of an elected though significantly disgraced president, the formation of an interim government containing protest leaders and members of a controversial right-wing group, the broad lack of diplomacy, and the local nature of the protests – it could hardly have been objected on moral or democratic grounds if the people and the political instruments of Crimea had called and voted in their own referendum. Many Crimeans may understandably feel themselves entitled to determine their region’s future – and regardless of the Ukrainian constitution, for after all, it was the Ukrainian parliament which unilaterally diminished Crimea’s autonomy in 1995, abolishing the post of President of Crimea and forcing the Crimean parliament to redraw and renegotiate Crimea’s constitution. The overt and intimidating Russian military presence must render the referendum which did take place illegitimate – a vote held under duress can never be acceptable – but it does not render it meaningless, because the will of Crimeans seems clear. Impelled to take a position in grossly unsatisfactory circumstances, the majority of Crimeans prefer to retain close connections with Russia.

The scenario in eastern Ukraine is different, however. It must be remembered that Crimea was – and will remain, in name at least – an autonomous republic, with its own parliament. It already possessed a significant degree of independence from the rest of Ukraine. This sense of distinctness has been enhanced by the continuing presence on Crimea of Russia’s Black Sea Fleet, which has been based at Sevastopol since the city’s founding in 1783. There is in fact no history prior to 1991 of the Ukrainian mainland and the Crimean peninsula existing together as one independent state: after the fall of Kievan Rus, the history of mainland Ukraine is one of Polish-Lithuanian control and the Cossack Hetmanate, while the history of Crimea is of the Crimean Khanate and the Ottoman Empire. Crimea only joined the Ukrainian SSR in 1954, transferred by Soviet Russia, and together they would remain tied to the Soviet Union until Ukrainian independence.

Ethnic Russians are in the majority in Crimea today: 59%, compared to 24% ethnic Ukrainians and 12% Crimean Tatars. In the east, where the ethnic balance is more even, there is a sense that economic attachment to Russia does not equate to close cultural attachment: people define themselves based less on narrow ethnic definitions, more in relation to their shared culture and their experiences building their cities together. If referendums were somehow called in the east on the issue of independence from Ukraine or integration with Russia, it is not clear which side would win. The east – bound in its past to the banks of the Dnieper as much as it is to the Russian Empire, and having suffered so much as part of the Soviet Union – has perhaps less cultural resonance for Russians than Crimea; while its loss would be much more costly for Ukraine, inevitably leading to a protracted and militarised engagement were Russia to try their hand.

Once more, any suggestion that Russia will do so amounts, at this stage, to speculation, carrying with it a palpable degree of scaremongering. For its part, Ukraine must look firmly ahead to the presidential elections scheduled for 25 May. These seem set to draw an array of candidates: from the oligarchy, the political elite, and the professional classes, and covering the whole of the political spectrum. Former Prime Minister Yulia Tymoshenko yesterday confirmed her candidacy, which may – along with the prospective candidacies from Svoboda and the militant Pravy Sektor – be cause for lament, as Ukraine needs neither divisive politics nor symbols of the persistent corruption that has been at the government’s head. Other potential candidates include the former boxer and opposition politician Vitali Klitschko, and the ‘Chocolate King’ Petro Poroshenko, an independent businessman who stands as the current favourite in polls despite not yet formally announcing his candidacy. Interim Prime Minister Yatsenyuk – who signed last Friday part of the Association Agreement with the EU whose suspension instigated the Euromaidan protests – could also still stand. Open elections and a real willingness to reform the political structure will guarantee nothing, but still affirm themselves as the best means for securing true Ukrainian independence, and for calming ongoing tensions in the east.

————

And why not give Gogol a final word? His Cossack horror story ‘A Terrible Vengeance’ – translated here by R. Pevear and L. Volokhonsky – contains one of his most famous descriptive passages. It depicts the Dnieper:

‘Master Danilo sits and looks with his left eye at his writing and with his right eye out the window. And from the window the gleam of the distant hills and the Dnieper can be seen. Beyond the Dnieper, mountains show blue. Up above sparkles the now clear night sky. But it is not the distant sky or the blue forest that Master Danilo admires: he gazes at the jutting spit of land on which the old castle blackens. He fancied that light flashed in a narrow window of the castle. But all is quiet. He must have imagined it. Only the muted rush of the Dnieper can be heard below, and on three sides, one after the other, the echo of momentarily awakened waves. The river is not mutinous. He grumbles and murmurs like an old man: nothing pleases him; everything has changed around him; he is quietly at war with the hills, forests, and meadows on his banks, and carries his complaint against them to the Black Sea.’

————————

Further reading:

The standard history of Ukraine in English is Ukraine: A History by Orest Subtelny (University of Toronto Press, 2009). Other acclaimed English-language histories of the country include Paul Robert Magocsi’s History of Ukraine: The Land and Its Peoples (University of Toronto Press, 2010) and Borderland: A Journey Through the History of Ukraine by Anna Reid (Phoenix, 2003). Timothy Snyder’s Bloodlands: Europe Between Hitler and Stalin (Vintage, 2011) provides a close reading of the devastation of Ukraine during the 1930s and 1940s. The most sustained study of Gogol’s works within a Ukrainian context is Edyta Bojanowska’s Nikolai Gogol: Between Ukrainian and Russian Nationalism (Harvard University Press, 2007).

A selection of news sources:

The BBC profiles Luhansk, from last December: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-25406861

Reuters reports on the death of a protester in Donetsk: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/13/us-ukraine-crisis-donetsk-idUSBREA2C20Z20140313

The International Business Times on the death of two in Kharkiv: http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/two-killed-ukraine-protesters-clash-kharkiv-1440436

A Guardian opinion piece following the deaths in Kharkiv: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/mar/20/ukraine-nationalist-attacks-russia-supporters-kremlin-deaths

Putin signs a bill on the integration of Crimea with the Russian Federation: http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-26630062

Reuters on the Ukrainian withdrawal from Crimea: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/24/us-ukraine-crisis-crimea-base-idUSBREA2N09J20140324

NATO commander Philip Breedlove on concerns over Transdniestria: http://www.reuters.com/article/2014/03/23/us-ukraine-crisis-idUSBREA2M09920140323

Former German Chancellor Helmut Schmidt comments on the sanctions: http://www.spiegel.de/politik/ausland/helmut-schmidt-verteidigt-in-krim-krise-putins-ukraine-kurs-a-960834.html

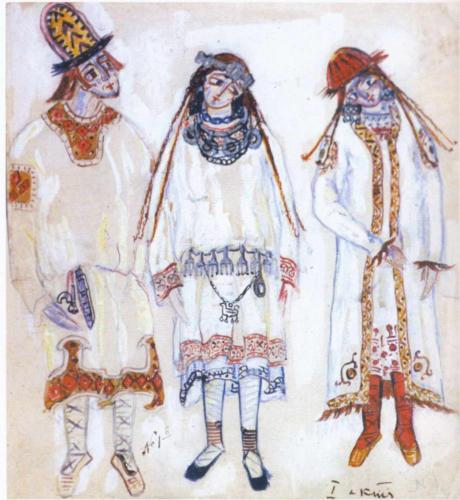

![Pierrot and Harlequin [Mardi-Gras] (1888-1890) - Paul Cezanne - Gallery of European and American Art - Moscow Musts](https://culturedallroundman.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/cezanne-pierrot-and-harlequin.jpg?w=467&h=580)