Here are a selection of documents and sources – videos, images, and text – relating to and referred to in the piece I just published, on the influence of Nicholas Roerich and Asiatic culture on Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring.

____

Mikhail Glinka, Ruslan and Lyudmila (1842) – Overture

____

Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Scheherazade, Op. 35 (1888)

____

Vladimir Soloviev, ‘Pan Mongolism’ (1894)

–

Pan Mongolism! The name is monstrous

Yet it caresses my ear

As if filled with the portent

Of a grand divine fate.

–

While in corrupt Byzantium

The altar of God lay cooling

And holy men, princes, people and king

Renounced the Messiah –

–

Then He invoked from the East

An unknown and alien people,

And beneath the heavy hand of fate

The second Rome bowed down in the dust.

–

We have no desire to learn

From fallen Byzantium’s fate,

And Russia’s flatterers insist:

It is you, you are the third Rome.

–

Let it be so! God has not yet

Emptied his wrathful hand.

A swarm of waking tribes

Prepares for new attacks.

–

From the Altai to Malaysian shores

The leaders of Eastern isles

Have gathered a host of regiments

By China’s defeated walls.

–

Countless as locusts

And as ravenous,

Shielded by an unearthly power

The tribes move north.

–

O Rus’! Forget your former glory:

The two-headed eagle is ravaged,

And your tattered banners passed

Like toys among yellow children.

–

He who neglects love’s legacy,

Will be overcome by trembling fear…

And the third Rome will fall to dust,

Nor will there ever be a fourth.

____

Golden bull figurine, from the Maikop kurgan (excavated 1897)

____

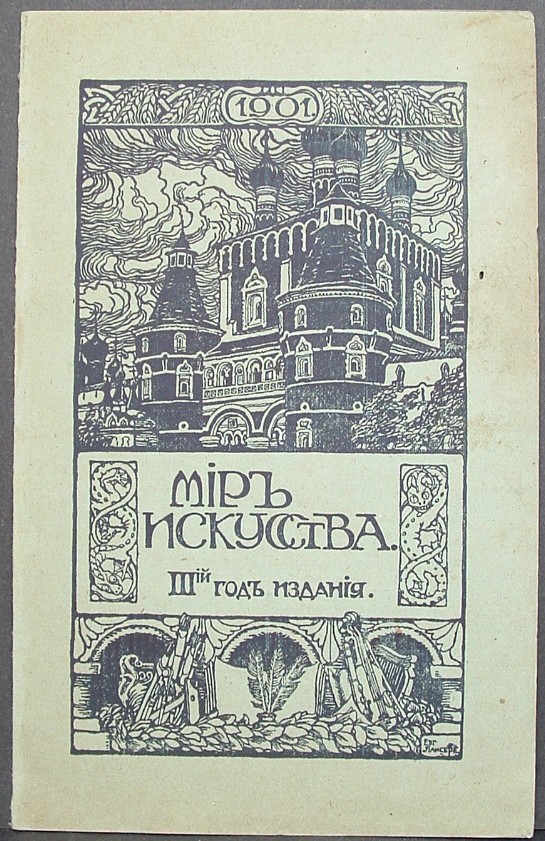

World of Art magazine, 3rd Edition (1901)

____

Nicholas Roerich, Guests from Overseas (1901)

____

Nicholas Roerich, Set Design for Act III of The Polovtsian Dances (1909)

____

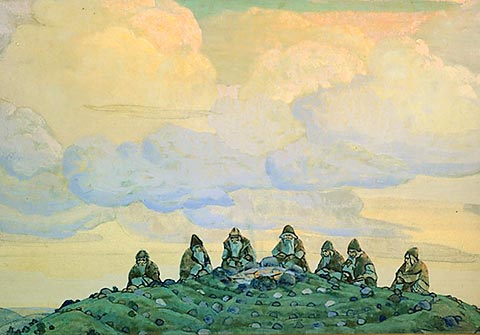

Nicholas Roerich, Preliminary Paintings for ‘The Great Sacrifice’ (the working title of The Rite of Spring) (1910)

____

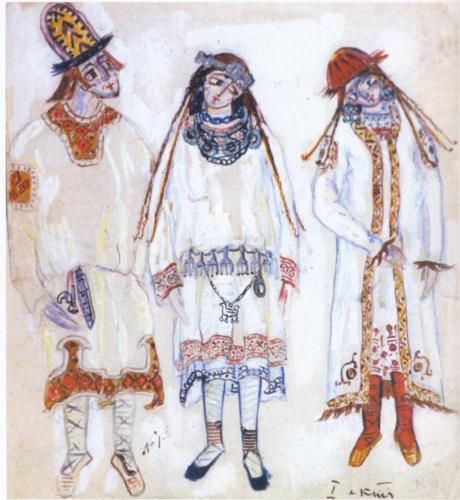

Nicholas Roerich, Costume Designs for The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Nicholas Roerich, Set Designs for The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Original Costumes for The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Igor Stravinsky, The Rite of Spring (1913)

____

Alexander Blok, The Scythians (1918)

–

You are millions. We are hordes and hordes and hordes.

Try and take us on!

Yes, we are Scythians! Yes, we are Asians –

With slanted and greedy eyes!

–

For you, the ages, for us a single hour.

We, like obedient slaves,

Held up a shield between two enemy races –

The Tatars and Europe!

–

For ages and ages your old furnace raged

And drowned out the roar of avalanches,

And Lisbon and Messina’s fall

To you was but a monstrous fairy tale!

–

For hundreds of years you gazed at the East,

Storing up and melting down our jewels,

And, jeering, you merely counted the days

Until your cannons you could point at us!

–

The time is come. Trouble beats its wings –

And every day our grudges grow,

And the day will come when every trace

Of your Paestums may vanish!

–

O, old world! While you still survive,

While you still suffer your sweet torture,

Come to a halt, sage as Oedipus,

Before the ancient riddle of the Sphinx!..

–

Russia is a Sphinx. Rejoicing, grieving,

And drenched in black blood,

It gazes, gazes, gazes at you,

With hatred and with love!..

–

It has been ages since you’ve loved

As our blood still loves!

You have forgotten that there is a love

That can destroy and burn!

–

We love all- the heat of cold numbers,

The gift of divine visions,

We understand all- sharp Gallic sense

And gloomy Teutonic genius…

–

We remember all- the hell of Parisian streets,

And Venetian chills,

The distant aroma of lemon groves

And the smoky towers of Cologne…

–

We love the flesh – its flavor and its color,

And the stifling, mortal scent of flesh…

Is it our fault if your skeleton cracks

In our heavy, tender paws?

–

When pulling back on the reins

Of playful, high-spirited horses,

It is our custom to break their heavy backs

And tame the stubborn slave girls…

–

Come to us! Leave the horrors of war,

And come to our peaceful embrace!

Before it’s too late – sheathe your old sword,

Comrades! We shall be brothers!

–

But if not – we have nothing to lose,

And we are not above treachery!

For ages and ages you will be cursed

By your sickly, belated offspring!

–

Throughout the woods and thickets

In front of pretty Europe

We will spread out! We’ll turn to you

With our Asian muzzles.

–

Come everyone, come to the Urals!

We’re clearing a battlefield there

Between steel machines breathing integrals

And the wild Tatar Horde!

–

But we are no longer your shield,

Henceforth we’ll not do battle!

As mortal battles rages we’ll watch

With our narrow eyes!

–

We will not lift a finger when the cruel Huns

Rummage the pockets of corpses,

Burn cities, drive cattle into churches,

And roast the meat of our white brothers!..

–

Come to your senses for the last time, old world!

Our barbaric lyre is calling you

One final time, to a joyous brotherly feast

To a brotherly feast of labor and of peace!

____

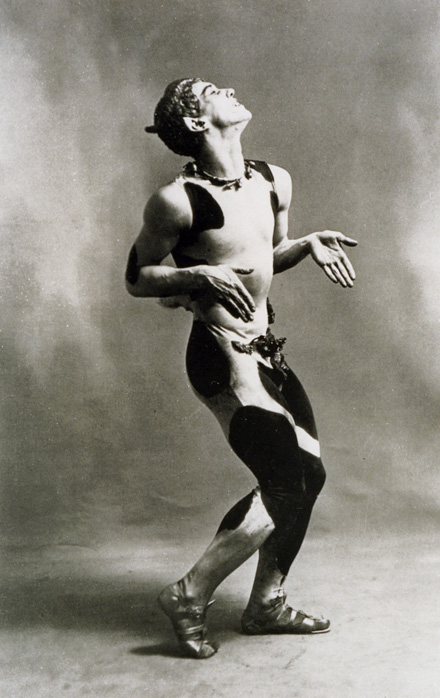

Vaslav Nijinsky

____

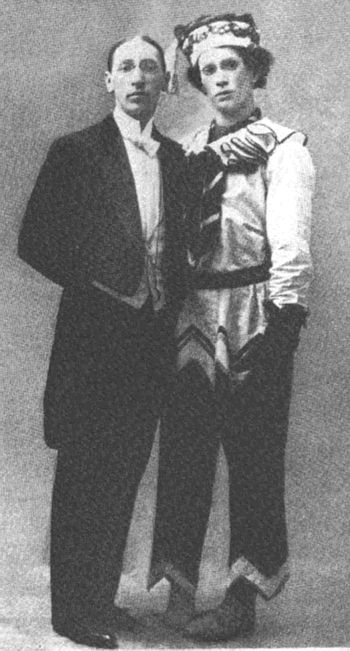

Stravinsky and Nijinsky

____

Credit for the two poems goes to From the Ends to the Beginning: A Bilingual Anthology of Russian Verse; a project hosted at: http://max.mmlc.northwestern.edu/~mdenner/Demo/index.html